Despite these complications for teaching, Melville does a masterful job of examining and investigating different types of racism and it is worthwhile to teach the novella in order to get students to investigate their own prejudices and biases.

The novella also reads somewhat like a detective novel, so it's easier to "sell" to students than Billy Bud (which I just didn't love in high school); moreover, Benito Cereno is short enough to teach in about 3-4 days (depending on the level your students are at), so it offers a logistical convenience that you wouldn't get from, say, Moby Dick.

The following blog post will look at methods for overcoming the difficulties of Melville's narrative strategies by engaging students in a discussion about perspective through studying both setting and different types of narrators and characters.

Setting

Captain Amasa Delano, an American from New England, spots a distressed ship near St. Maria, a dessert island off the coast of Chile. He goes to investigate and he finds the San Dominick in an odd state. The Spanish captain, Don Benito Cereno is one of only a very few white people on board a ship that is otherwise occupied by black slaves. The slaves are not in chains, but wander freely around the ship.

Cereno explains that the ship has had a succession of bad luck, so that the white crew has mostly died of fever and injury, but that the slaves have not only survived better but also been instrumental to the safety and survival of the remaining Spanish on board. Cereno appears to be unwell either in body, mind, or soul, and he relies particularly on his servant Babo.

Delano alternates between fascination and disgust with Cereno, whom he judges to be too aristocratic. Delano suspects that Cereno is lying about something and he spends the majority of the novel attempting to get to the bottom of it while also offering help to the people in need.

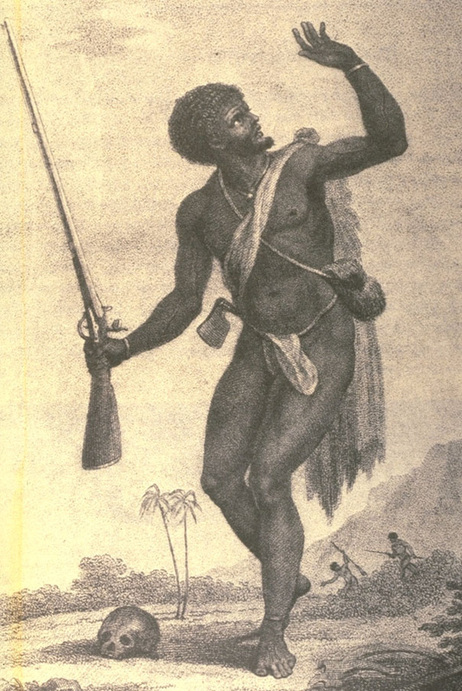

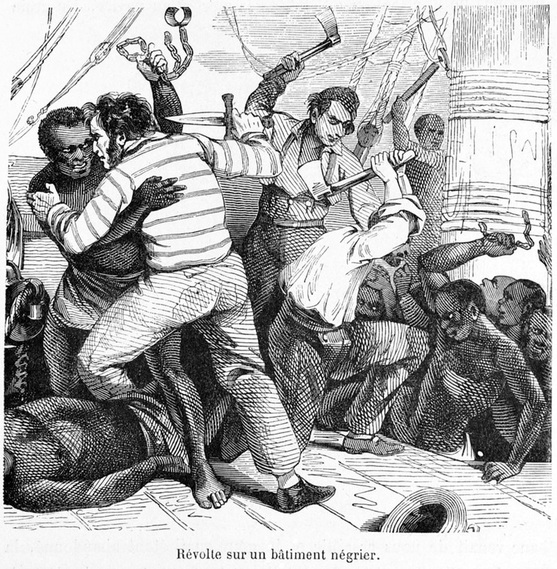

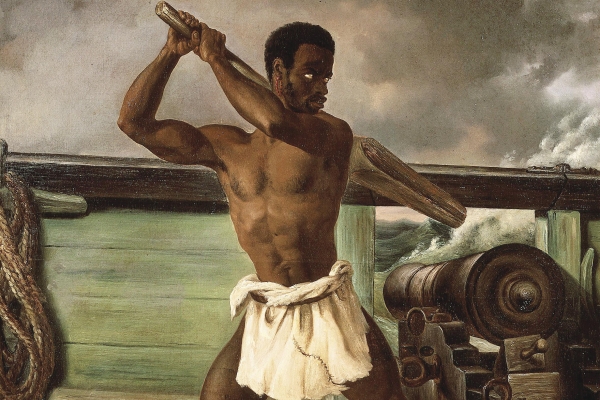

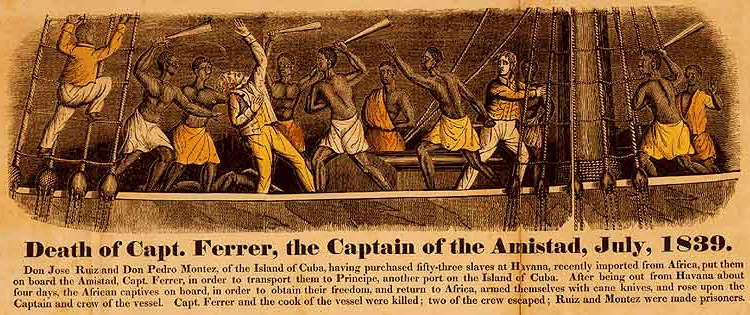

[SPOILER ALERT] Near the end of the novel, Melville reveals that there has been a slave revolt, and that Babo is only pretending to be a perfect slave in order to get the needed supplies from Delano (and perhaps commandeer Delano's ship as well). He has led the mutiny (including the murders of the crew members), and he intends to force Cereno to sail him and the other slaves back to Senegal. [END OF SPOILER ALERT]

One way that Melville is able to immediately focus his readers attention on the theme of perception and bias is in the setting of the ship at sea. Here is the initial description of the San Dominick:

[It] appeared like a white-washed monastery after a thunder-storm, seen perched upon some dun cliff among the Pyrenees. But it was no purely fanciful resemblance which now, for a moment, almost led Captain Delano to think that nothing less than a ship-load of monks was before him. Peering over the bulwarks were what really seemed, in the hazy distance, throngs of dark cowls; while, fitfully revealed through the open port-holes, other dark moving figures were dimly descried, as of Black Friars pacing the cloisters... the living spectacle [a ship at sea] contains, upon its sudden and complete disclosure, has, in contrast with the blank ocean which zones it, something of the effect of enchantment. The ship seems unreal; these strange costumes, gestures, and faces, but a shadowy tableau just emerged from the deep, which directly must receive back what it gave.

- What do you make of this description of the ship? Why describe the ship as a monastery, a castle, an enchantment? What effect does that have?

- What does it matter that the ship seems to be a shape-sifter in this description? Why make this setting so ephemeral?

Narrative Conventions

Viewpoint character:

One of the most common narrative voices, used especially with first- and third-person viewpoints, is the character voice, in which a conscious "person" (in most cases, a living human being) is presented as the narrator. In this situation, the narrator is no longer an unspecified, omniscient entity; rather, the narrator is a more relatable, realistic character who may or may not be involved in the actions of the story and who may or may not take a biased approach in the storytelling. If the character is directly involved in the plot, this narrator is also called the viewpoint character. The viewpoint character is not necessarily the focal character. We can think of the viewpoint character as the "one who watches," or--to borrow a metaphor from film--the character who acts like a director in a movie, guiding our own gaze through a particular lens or viewpoint.

Focal character:

The character on whom the audience is meant to place the majority of their interest and attention. He or she is almost always also the protagonist of the story; however, in cases where the "focal character" and "protagonist" are separate, the focal character's emotions and ambitions are not meant to be empathized with by the audience to as high an extent as the protagonist (this is the main difference between the two character terms). The focal character is mostly created to simply be the "excitement" of the story, though not necessarily the main character with whom the audience emotionally identifies. The focal character is, more than anyone else, "the person on whom the spotlight focuses; the center of attention; the man whose reactions dominate the screen." Going back on to our film analogy: if the viewpoint character is like the director, then the focal character is like a movie star.

- How would you characterize Don Benito Cereno and Capt. Amasa Delano? Is one the viewpoint character and the other the focal character? Who would you say is the protagonist (if there is one)?

- How do these definitions help us to understand the way that Melville shapes his story? How would the story be different if, say, Babo were the viewpoint or the focal character?

These questions lead us to then characterize if our viewpoint character, Captain Delano, is a reliable narrator or not.

[Don Benito's] mind appeared unstrung, if not still more seriously affected. Shut up in these oaken walls, chained to one dull round of command, whose unconditionality cloyed him, like some hypochondriac abbot he moved slowly about... [With] nervous suffering [he] was almost worn to a skeleton…half-lunatic.

Even the formal reports which, according to sea-usage, were, at stated times, made to him by some petty underling, either a white, mulatto or black, he hardly had patience enough to listen to, without betraying contemptuous aversion.

[In] him was lodged a dictatorship… [Authority] obliterates alike the manifestation of sway with every trace of sociality; transforming the man into a block, or rather into a loaded cannon, which, until there is call for thunder, has nothing to say.

But probably this appearance of slumbering dominion might have been but an attempted disguise to conscious imbecility.

Questions to ask:

- This rapid change in characterization happens over three short pages. How can we paraphrase these descriptions—what are all of the ways that Capt. Delano interprets Benito Cereno?

- Does the rapid change of characterization affect how you see Capt. Delano at all? Does it matter that he can’t make his mind up about Benito Cereno?

- How reliable are Delano's perceptions of reality? What tendencies in particular make him an unreliable interpreter of the behavior he sees manifested on board the San Dominick?

- What are other things that Captain Delano might be looking at while on board?

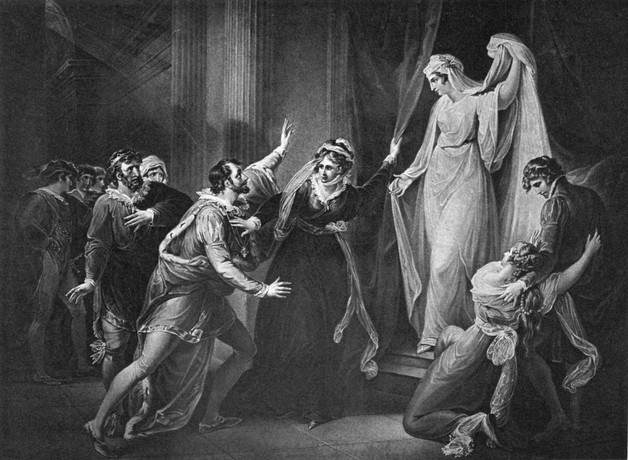

Anagnorisis

That moment, across the long-benighted mind of Captain Delano, a flash of revelation swept, illuminating, in unanticipated clearness, his host's whole mysterious demeanor, with every enigmatic event of the day, as well as the entire past voyage of the San Dominick. He smote Babo's hand down, but his own heart smote him harder. With infinite pity he withdrew his hold from Don Benito. Not Captain Delano, but Don Benito, the black, in leaping into the boat, had intended to stab... Both the black's hands were held, as, glancing up towards the San Dominick, Captain Delano, now with scales dropped from his eyes, saw the negroes, not in misrule, not in tumult, not as if frantically concerned for Don Benito, but with mask torn away, flourishing hatchets and knives, in ferocious piratical revolt.

There is something in the negro which, in a peculiar way, fits him for avocations about one's person. Most negroes are natural valets and hair-dressers; taking to the comb and brush congenially as to the castinets, and flourishing them apparently with almost equal satisfaction. There is, too, a smooth tact about them in this employment, with a marvelous, noiseless, gliding briskness, not ungraceful in its way, singularly pleasing to behold, and still more so to be the manipulated subject of. And above all is the great gift of good-humor. Not the mere grin or laugh is here meant. Those were unsuitable. But a certain easy cheerfulness, harmonious in every glance and gesture; as though God had set the whole negro to some pleasant tune.

Prof. Grandin explores the historical records surrounding the events upon which Melville based his novella, and he develops the reading that "Benito Cereno is one of the bleakest pieces of writing in American literature... the novella reads like a devil's edition of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, which had appeared a few years earlier. Where Stowe made her case for abolition by presenting Southern slaves as Christlike innocents and martyrs, Melville's West Africans are ruthless and deceitful. They act like Toms—but they are really Nat Turners."

The historical research and literary analysis are in the service of his larger argument that Captain Delano represents a new kind of American racism; the Captain's embodiment of the myth of self-creation needs Babo, the slave, to work as a point of contrast. In this argument, Grandin attempts to explain how the "fetish... of the ideal of freedom" came about at the same time as the growth of the slave industry.

Whether or not you want to make connections to modern historiography and politics, it is useful to consider how many events in this story would be different if told from Babo's point of view. This could be the grounds for a creative writing assignment!

We might then ask what the implications are of this narrative technique: does Melville want to expose all of Delano's lazy, racist thinking and showcase how resourceful and intelligent African men can be when fighting for their freedom? Or does this portrait of a murderous, manipulative slave collapse Babo (and African men in general?) into the category of evil? (This set of questions resonates with a similar discussion of Melville's novella in relationship to the politics involving the war on terror and US military presence in Afghanistan. See this post on the blog, Better Living through Beowulf, run by Prof. Robin Bates of St. Mary's College of Maryland.)

The Deposition

As for the black—whose brain, not body, had schemed and led the revolt, with the plot—his slight frame, inadequate to that which it held, had at once yielded to the superior muscular strength of his captor, in the boat. Seeing all was over, he uttered no sound, and could not be forced to. His aspect seemed to say, since I cannot do deeds, I will not speak words.

- Most of the confusion in interpreting Benito Cereno arises from the latter part of the story. It is easy to see that Delano's view of blacks is stupid and wrong, but does Melville present Benito Cereno's view of blacks as a corrective to the stereotype, or merely as another stereotype? Does the Deposition represent the "truth"?

- How does the language of the Deposition differ from the language Melville uses elsewhere in the text? What makes us take it for the "truth"?

- What is Benito Cereno's interpretation of events, as opposed to Delano's initial interpretation? How does he explain the slaves' revolt?

- Does the Deposition indirectly provide any alternative explanations of why the blacks may have revolted? What does it tell us about the blacks' actual aims? How do they try to achieve those aims?

- What is the narrative point of view of the few pages following the Deposition? How do you interpret the dialogue between the two captains? Does it indicate that either Delano or Cereno has undergone any change in consciousness or achieved a new understanding of slavery as a result of his ordeal?

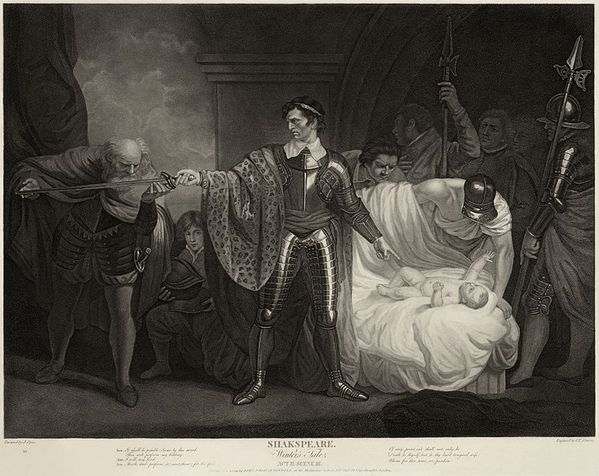

- Why does Babo stop talking anyway? How does this mirror and/or parody Shakespeare’s white character, Iago? If we think about this story with the races switched, (as it is in Othello, with the higher ranking officer as the Moor Othello and the lower ranking officer as the Venetian Iago) how would that change things? If we think about this story as being a tragedy (like Othello) then who is the tragic hero?

Some months after, dragged to the gibbet at the tail of a mule, the black met his voiceless end. The body was burned to ashes; but for many days, the head, that hive of subtlety, fixed on a pole in the Plaza, met, unabashed, the gaze of the whites.

We learn within a few lines that "three months after being dismissed by the court, Benito Cereno, borne on the bier, did, indeed, follow his leader." This sentence--the way in which Melville communicates Don Benito's death--refers to a constant refrain throughout the book. It appears first as the painted or chalked slogan written on the forward side of the pedestal below the canvas on the San Dominick and then later comes up as a threat from Babo. It is worthwhile to go back to these three instances and to consider who is the "leader" and who is the audience in each case. What does this refrain do for the text, and how does it help us to identify the story's racial politics?

Students will express understandable reluctance to think of Babo as the unacknowledged hero of the story, even if they can see him as a freedom fighter. I say that their reluctance is "understandable" simply because Babo is so violent and vengeful, not traits that we typically think of as heroic.

It is easy to forget that pretty much every evil thing that Babo did to the Spanish had already been done to him and the other Senegalese by the Spanish slavers. Ask students to consider that the slave trade was widely known to be violent and dangerous, especially for slaves who were in transit on ships (such as during the Middle Passage across the Atlantic). Babo's violence is in response to violence that has been done to him, a part of the story that Melville silently omits.

Collapsing Babo into the category of "evil" only works if we completely ignore the history of violence we know he has suffered or if we attempt to think about slavery as a protective, benevolent institution. Disliking Babo because he isn't more like the "Christlike innocents and martyrs" we are comfortable with through Uncle Tom's Cabin signals the reader's discomfort with black anger; our dislike says more about what we expect from almost all our heroes and our representations of black characters than it says about the book's politics. Perhaps Melville's seemingly prophetic emphasis on bias and perspective even forces us to examine our own bias in 2014.

Melville's text is rich and complicated, but it is deeply rewarding for extending the discussion of racism in America beyond the Civil War and the Jim Crow South. It pairs really well with contemporaneous abolitionist texts like Harriet Jacob's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which masks and channels black anger in order to make an abolitionist book more appealing to white female readers looking for a sentimental novel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed