One of the main goals of my course was to think about how form (such as genre) might offer Shakespeare ways to produce competing theories of gender, sex, performance, and sexuality. To this end, I spent a whole day of transition in between the festive comedies and the tragedy, Antony and Cleopatra.

Here are the materials that I asked my students to read for our transition day:

- Joseph W. Meeker, “The Comic Mode” in The Norton Critical Edition of As You Like It pp. 220-234.

- Francis Beaumont’s “Salmachis and Hermaphroditus” in the Texts and Contexts Edition of Twelfth Night, pp. 225-236.

- Iconography of marriage from emblem books [a PDF I made of the emblems that I discussed in this previous post]

Since I have already discussed the emblems of marriage in my post last summer, I won't rehash that here other than to say that this was enormously successful in the classroom. My students had a lot to say about these images and the contradictory ways that they emblematize marriage. Instead, I will focus this blog post on strategies for close-reading Beaumont's poem, which would work well in teaching any of Shakespeare's cross-dressing plays.

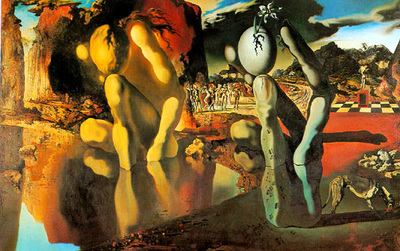

The Myth In Classical and Neoclassical Art

Beaumont's poem

Diana being hunting on a day,

She saw the boy upon a green bank lay him,

And there the virgin huntress meant to slay him;

Because no nymphs would now pursue the chase,

For all were struck blind with the wanton's face…

She turn'd and shot, but did of purpose miss him,

She turn'd again, but could not choose but kiss him.

Then the boy ran: for some say had he staid,

Diana had no longer been a maid.

Phœbus so doted on this roseate face,

That he bath oft stol'n closely from his place,

When he did lie by fair Leucothoë's side,

To dally with him in the vales of Ide.

Hermaphroditus

His cheek is sanguine, and his lip as red, |

SalmachisSo fair she was, of such a pleasing grace, |

What does it matter then that both male and female character gets a blazon? Does the blazon turn the male gaze onto the body of Hermaphroditus, or is the larger point here that these two characters are somehow alike, even before they have met each other?

The idea that these two characters are somehow alike is important because the myth of Narcissus comes up repeatedly in this poem.

The first instance: the two meet each other at the river where Narcissus died.

For this was the bright river where the boy [Narcissus]

Did die himself, that he could not enjoy

Himself in pleasure, nor could taste the blisses

Of his own melting and delicious kisses.

Here did she [Salmacis] see him [Hermaphroditus], and by Venus' law

She did desire to have him as she saw.

- Why is the myth of Narcissus important to the myth of Salmacis and Hermaphroditus—even before they ever talk to each other?

- If Salmacis and Hermaphroditus are sort of alike through their respective blazons… are the references to Narcissus foreshadowing that they will fall into a dangerous sort of love because they will see themselves reflected in each other?

The second instance: Hermaphroditus falls in love with the reflection of his own image that he sees in the glassy mirror of Salmachis' eyes.

That she had won his love, but that the light

Of her translucent eye did shine too bright;

For long he looked upon the lovely maid,

And at the last Hermaphroditus said:

"How should I love thee, when I do espy

A far more beauteous nymph hid in thy eye?

When thou dost love let not that nymph be nigh thee,

Nor, when thou woo'st, let that same nymph be by thee;

Or quite obscure her from thy lover's face,

Or hide her beauty in a darker place."

By this the nymph perceived he did espy

None but himself reflected in her eye.

- How does this reference build on our conversation?

- Is falling in love with someone related to self-love?

- Does the poem present a perversion of love, or a commentary on the normal experience of erotic love? Is Salmachis more or less self self-centered that Hermaphroditus?

The third instance: Salmachis uses Narcissus as a warning to Hermaphroditus:

Remember how the gods punish'd that boy,

That scorn'd to let a beauteous nymph enjoy

Her long-wished pleasure; for the peevish elf,

Loved of all others, needs would love himself:

So may'st, thou love perhaps: thou may'st be blest

By granting to a luckless nymph's request.

- How does Salmachis turn Narcissus into a threat?

- Is this all sophistry (she is presenting sexual love as a “gift” and the withholding of sexual love as “selfish”), or does she kind of have a point?

- How much should we trust her?

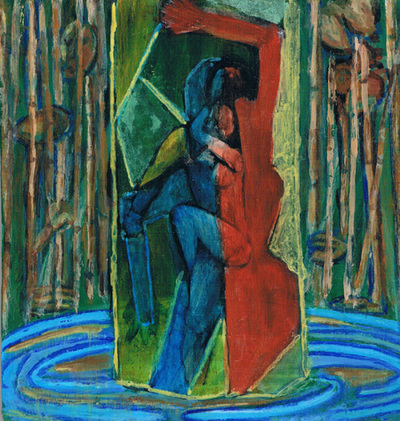

Narcissus in Modern and Postmodern Art

Salmachis on becoming more masculine:

Were thou a maid and I a man, I'll show thee

With what a manly boldness I could woo thee.

Salmachis on Hermaphroditus becoming more feminine:

Why were so bashful, boy? Thou hast no part

Shows thee to be of such a female heart!

- What assumptions does Salmachis (or Beaumont) make about masculinity and femininity?

- What does it matter that Salmachis is already masculine/bold and Hermaphroditus is already feminine/bashful?

[The brook's] pleasant coolness when the boy did feel,

He thrust his foot down lower to the heel.

O'ercome with whose sweet noise he did begin

To strip his soft clothes from his tender skin…

When beauteous Salmacis a while had gazed

Upon his naked corpse, she stood amazed,

And both her sparkling eyes burnt in her face,

Like the bright sun reflected in a glass…

Then rose the water-nymph from where she lay,

As having won the glory of the day,

And her light garments cast from off her skin,

"He's mine," she cried, and so leapt sprightly in.

- Why does Salmachis believe she has “won the glory of the day”?

- Is love a contest or a competition? How so?

- If so, who’s winning and how do you know?

If you do keep the emblems (which I recommend) then this would be a good place to show them in order to ask your class to think about if marriage could be understood as a woman "winning" a spouse, particularly one who might otherwise want to remain single, unattached, or promiscuous.

By the way, this logic is alive and well in certain misogynistic corners of the internet. The same anti-feminist website that I referenced in an earlier blog post mentions in its contradictory "community beliefs" page that 1) Past traditions and rituals that evolved alongside humanity [such as marriage] served a net benefit to the family unit, and 2) Men will opt out of monogamy and reproduction if there are no incentives to engage in them. These men argue, like some of the marriage emblems and possibly Beaumont in his poem, that marriage is a trap that women set for men, which ultimately robs men of their agency and power. Female sexuality is, according to this logic, dangerous for the male ego. This leads to my final set of questions about Beaumont's poem.

Yet still the boy, regardless what she said,

Struggled apace to overswim the maid;

Which when the nymph perceived she 'gan to say,

"Struggle thou may'st, but never get away;

So grant, just gods, that never day may see

The separation 'twixt this boy and me!"

The gods did hear her prayer, and feel her woe,

And in one body they began to grow.

She felt his youthful blood in every vein,

And he felt her's warm his cold breast again;

And ever since was woman's love so blest,

That it will draw blood from the strongest breast,

Nor man nor maid now could they be esteem'd,

Neither and either might they well be deem'd

When the young boy, Hermaphroditus, said,

With the set voice of neither man nor maid:

"Swift Mercury, thou author of my life,

And thou my mother, Vulcan's lovely wife;

Let your poor offspring's latest breath be blest

In but obtaining this his last request:

Grant that whoe'er, heated by Phœbus' beams,

Shall come to cool him in these silver streams,

May never more a manly shape retain,

But half a virgin may return again."

- What is Salmachis’ prayer?

- How would you characterize their physical union?

- What is Hermaphroditus’ prayer?

- What is the difference between "neither" and "either" in the highlighted passage?

- What does it matter that Hermphroditus gets the last words?

As we saw in the post about Act 5 of As You Like It, Rosalind accretes gender signifiers onto herself. If she is a symbolic hermaphrodite by the end of the play, then this is a source of power for her because it allows her to be both male and female. Comedy allows for this flexibility. As we will see in the upcoming posts about Antony and Cleopatra, Antony's symbolic figuration as a hermaphrodite (especially in Caesar's articulation of his gender) is as "neither" male nor female. Antony's identity is emptied out of meaning, dissolved away completely. Tragedy does not allow him the accretion of gender identity that it allows Rosalind.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this blog post, I ask my students to read a critical essay on genre by Joseph Meeker. This is a fabulous essay and one that is worth reading with your students even if your main focus is not on gender. Briefly, Meeker argues that tragedy and comedy have diametrically opposed worldviews, with tragedy as taking a human-centric perspective and comedy as taking an ecology-centric one.

Tragedy

Especially arises from Western Civilization, at key times

Imitates man’s suffering, greatness and nobility Assumes metaphysical presuppositions: 1) that the universe cares about human life, 2) that there is something bigger than our survival, something worth dying for, 3) that man is essentially superior to the animal world (including his own body) and should dominate his environment, 4) that individual people can show heroism, strength, dignity, and nobility in the face of chaos and destruction. Ends in death |

Comedy

A universal literary genre, found in all cultures at all times

Imitates man’s ignorance, amorality, and adaptability Does not make tragedy’s metaphysical assumptions, and thus implies the following: 1) that nature is indifferent to—not in opposition to—humanity, 2) that survival is a worthy goal, 3) that mankind is not superior to the animal world (especially his own body) and should change himself rather than change the environment, and 4) that individual needs do not take priority over the group’s survival. Ends in marriage |

[Comedy] and ecology are systems designed to accommodate necessity and to encourage acceptance of it, while tragedy is concerned with avoiding or transcending the necessary in order to accomplish the impossible... [The] tragic heroes preserved in literature are the products of metaphysical presuppositions which most people can no longer honestly share… The philosophical props and settings for genuine tragic experience have disappeared. Moderns can only pretend to tragic heroism, and that pretence is painfully hollow and melodramatic in the absence of the beliefs that tragedy depends on.

- As we move away from Twelfth Night and As You Like It toward Antony and Cleopatra, we are moving from comedy to tragedy.

- How are Twelfth Night and As You Like It accommodating necessity and encouraging the acceptance of it? How are they “comic” according to this definition? Is this “nature’s bias” at work again—or is it something different?

- As we move into Antony and Cleopatra, I want you to think about the “beliefs” that make this play a tragedy? What is the system of belief that is “greater than” Antony’s survival? What is it that is worth dying for?

- Does the figure of the hermaphrodite or the iconography of marriage present a comic or a tragic worldview (as Meeker presents them)?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed