I like to assign the Norton Critical Edition of the poem, which uses Marie Borroff's translation and includes some canonical but accessible critical essays. I reference this edition in the following blog post, including some of the essays in the back.

For more advanced students, it's fine to split the poem up into three days: Fitts I-II, Fitt III, and Fitt IV. For younger or less advanced students, I would spend one day per Fitt.

There are at least three definitions that you will want to go over before diving into the poem. Either these terms refer to concepts that will be foreign to students, or they are middle English words that have "false friends" in modern English:

- Trouth (many alternate spellings): a word to describe the interrelated concepts of loyalty, fidelity, honesty, integrity, the keeping of promises and oaths, and justness and innocence. Related to our modern English words truth and troth, it goes far beyond simply "telling the whole story without any lies."

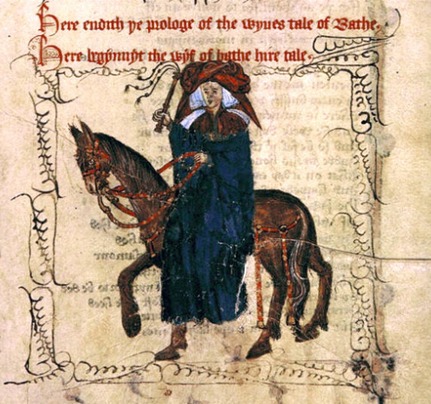

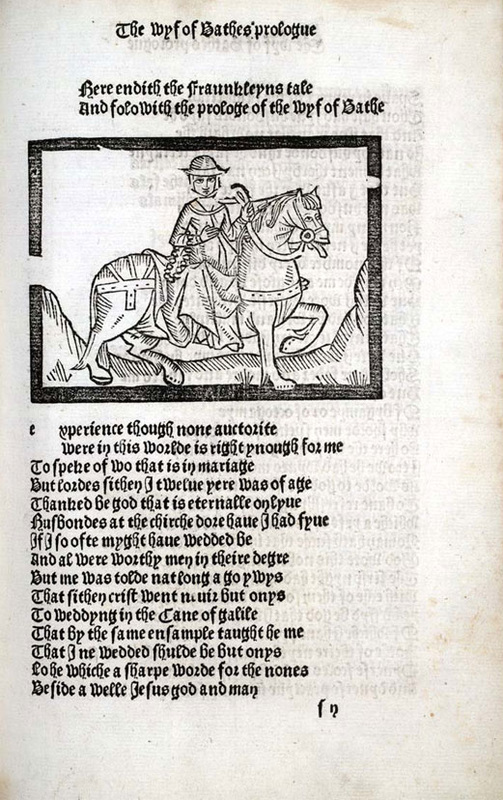

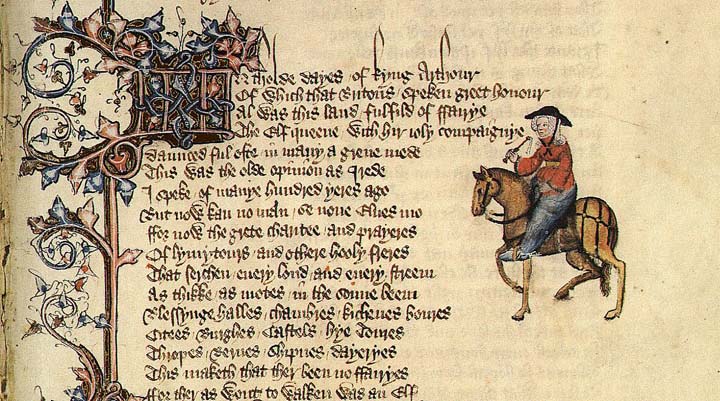

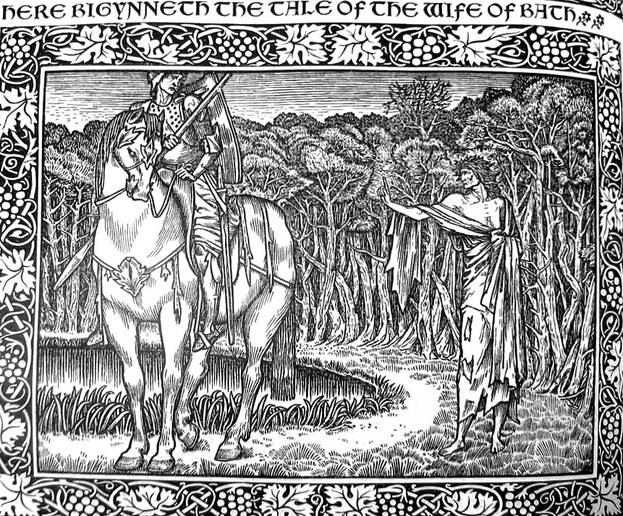

- Gentilesse: a word to describe both the kindness and goodness that everyday people can practice and also the state of being part of the landed nobility or the "gentils". Its meaning was contested during the time of the writing of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (see the Wife of Bath's Tale in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales), but we cannot quite divorce gentleness from gentility in this time period. I have learned from my medievalist friend, Kristen Aldebol, that asking students to think about what it means to call someone a "gentleman" is a good way to get them thinking about how class is still attached to the concept in our modern use of the word "gentle."

- Translatio imperii: (Latin for "transfer of rule") originating in the Middle Ages, translatio imperii is a concept for describing history as a linear succession of transfers of an empire. In England, this is manifested in Galfridian historiography (i.e., English history that takes its cues from Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae), which argues that Brutus of Troy (son of Aeneas) is the "founder" of Britain. The empire thus transfers from Troy to Britain.

I ask students to sign up for a motif to trace. Obviously some of these motifs are more exciting and engaging than others, but students really like taking ownership of their own special motif:

Motifs:

|

Agreements, covenants, and bargains:

Bible stories: Birds: Blood and the color red: Cold, winter, and the dark: Colors, especially green, white, and gold: Cutting tools and cutting: Embroidery, weaving, and silk: Fairyland, things of fairies and “fay”: Fear and/or guilt: Feasts, music, food and meals: Gems and jewelry: |

Heads (of animals and of people):

Knots: Places of prayer: Religious holy days and yearly seasons: Saints, masses, and matins: Sexual behavior or temptation counts: Shields and armor: Spousal and family relationships: The Trojans: Wild places and animals (not birds): Women and discussions about women: Youth and old age: |

In the blog post below, I will share my reading questions for each Fitt or part of the poem.

Fitt I

Arthur is said to be the "most courteous of all" British Kings (ll. 26). What are the characteristics of his court? His knights? His Queen?

As you read, pay attention to descriptive and narrative details. Why are they included? What do they signify? For example, the narrator describes the knights and ladies at Arthur’s feast as “fair folk in their first age” (54). What does that mean? Why does he characterize them in this way? How does the Green Knight reinterpret the “first age” of the courtiers?

Notice the descriptive details the narrator mentions regarding the Green Knight. What kind of character is he?

Pay attention to the introduction of the knight Gawain. How does he distinguish himself in the opening scenes? How is he different from the other knights? Does he fulfill a chivalric duty that the other knights neglect? What is his relationship to the ideal of "courtesy"?

Does the Green Knight play by the rules of courtesy? Does he seem like a negative or a positive figure in this section of the poem?

Fitt II

Gawain is stalwart and strong out in the wilderness, but once he gets inside the castle he has all his armor taken off of him, the wine goes to his head, and he spends an awful amount of time lying in bed. Is he merely recovering from fatigue or does the poet suggest that he is losing strength because of the castle? On the pentangle, one of the five points represents Gawain’s five fingers. What do hands symbolize? Is Gawain’s possible loss of physical strength related to the five fingers symbolized by the pentangle? How so?

Notice when Gawain prays to Jesus and Mary, calling on them for help, guidance, or aid. In what part in the narrative does he seem connected to Jesus and Mary? At what point in the narrative does he seem preoccupied with other things? How does this develop the symbolism of the pentangle?

Characterize the Lord of the castle in lines ll. 842-849 and in ll. 1079-11-25. What other character in the poem does he resemble in his physical stature and/or age and in his proclivity for seemingly harmless games? Why might that be important?

Fitt III

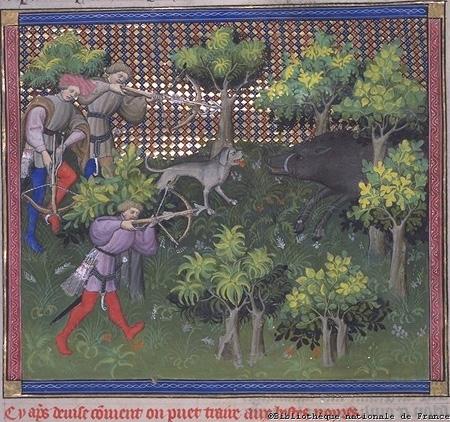

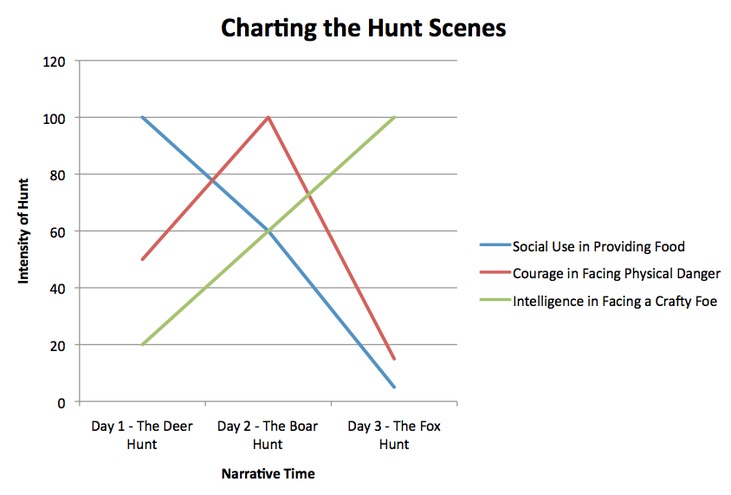

Day 1: What does the Host hunt? How does he hunt it? What does the Lady do to Gawain? Is she the hunter or the hunted? How is Gawain similar to the animal hunted in the larger context of the poem?

Read ll. 1851-1858, wherein Gawain accepts the Lady’s offer of the magical Green Girdle. This is the crucial moment of the poem that is sometimes compared to the temptation of Adam by Eve. On what levels does Gawain fail and/or “fall” here? If we think about the poem as a Christian allegory, what does his action (accepting the green girdle) represent? What does it say about him as a human being and as a knight? How harshly do you think we should or are meant to judge him?

What is the poet’s attitude toward "courtly love”? Which characters represent that tradition? In traditional "courtly love," a knight performs feats of valor for a lady he loves who is generally not his wife. He aspires to win her love by proving his worthiness, chivalric merit, etc. through "love service"--doing her will and trying to help her and be worthy of her regardless of her treatment of him. Does Gawain serve a lady in the poem? If so, whom does he serve? Is there a more "traditional" depiction of the courtly lady? What is the poet's (and Gawain's) attitude toward Lady Bertilak? What does that imply about "courtly love"?

Fitt IV

Gawain is accused for a second time in the poem of being an imposter (ll. 2269-2273). Compare the Green Knight’s accusation that Gawain is an imposter to Lady Bertilak’s similar claim (ll. 1293-95). What does it matter than Gawain (the real man) is continuously being compared to his reputation (a social idea of himself)? Does this comparison have an impact on the poem… (the poet presents the ideal of a chivalrous knight, but then maybe undercuts it by making Gawain seem less like a romance hero—greater in degree to his fellow men—and more like a comic hero—equal in degree to both his fellow men and his environment.) What is the effect? See the Davenport essay, pp. 141-142.

How is Gawain’s reaction to the Green Knight at the Green Chapel like a confession? Is it a better confession than the one he gives to the priest in Part III? Why or why not? Make sure you go over the sacrament of confession with the class.

Close read ll. 2374-2384. What sins does Gawain confess? On pp. 149-150 of our text, scholar Ralph Hanna III argues that the sins Gawain identifies don’t make sense in the context of the poem. (See the past paragraph on p. 149 and the first paragraph on p. 150). In other words, the narrator takes pains to undermine Gawain’s analysis of his own sins. Do you agree with Gawain that these are his chief sins?

Close read ll. 2374-2384. What sins does Gawain confess? Some of these sins are really the same (i.e., greed and coveting are basically the same thing). Group the sins into categories. With these categories in mind, go back to three temptation scenes with Lady Bertilak. Does she only tempt Gawain with lust, or does she tempt to sin along the lines he mentions. How much should we seriously consider his argument than women are behind all of men’s sins?

In an essay in the back of our critical edition—“Unlocking What’s Locked: Gawain’s Green Girdle”—literary scholar Ralph Hanna III argues that there are at least 4 contradictory ways that the characters within the text define the symbolic significance of the green girdle. How does Lady Bertilak construct the meaning of the girdle (1851-1854)? How does Gawain construct the meaning of the girdle (2439-2438)? How does the Green Knight construct the meaning of the girdle (2395-2399)? How does the Arthurian court construct the meaning of the girdle (2513-2518)?

At the end of the poem, the Green Knight declares that Gawain is the best of all Arthurian knights; this opinion is shared by the Arthurian court but not by Gawain. Why does he think so? Why does Gawain disagree? Does the court’s failure to understand the significance of Gawain’s experience change our opinion of the people at the court? Is Gawain a savior figure for the Arthurian court?

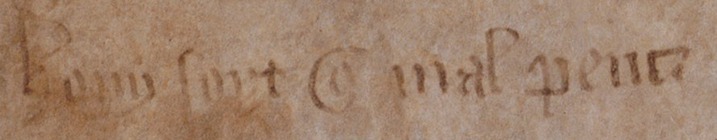

Why might the poet choose to remind the audience of the connection between Arthur, Brutus, and the Trojan refugee Aeneas at the end of the narrative? In the light of these translatio reference here and at the beginning of the poem, what do you make of the French motto “Honi Soit Qui Mal Pense” found at the end of the poem? The some translates this line, “Shame be to the man who has evil in his heart”; an equally plausible rendering is “shame on whoever thinks ill [of him/it].” How can this motto be connected to the themes of the poem as a whole or to the translatio references which frame the narrative itself?

Gawain confronts and learns to accept his own mortality; he learned that he too is a part of the natural world—mutable, subject to time, imperfect, green. Sure this is a Christian poem; but it’s also supremely human. His “sins” (“cowardice and covetousness”) are not just against God but against his own humanity. By taking the girdle (the magic delusion that we don’t have to face limits) Gawain shows that he covets life over death, he refuses to acknowledge his own humanity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed