I am using a "Texts and Contexts" approach to this course. Every class meeting, students will come to class having read contextual material in addition to an act of Shakespeare's play. I am really excited about the transitional material between As You Like It and Antony and Cleopatra. Students will read Francis Beaumont’s “Salmachis and Hermaphroditus”and look at a selection of icons allegorizing marriage from early modern emblem books.

- In Mark 10:8: they twain shall be one flesh: so then they are no more twain, but one flesh.

- Genesis 2:24: Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh.

- Ephesians 5:32: a man [shall] leave his father and mother, and shall be joined unto his wife, and they two shall be one flesh.

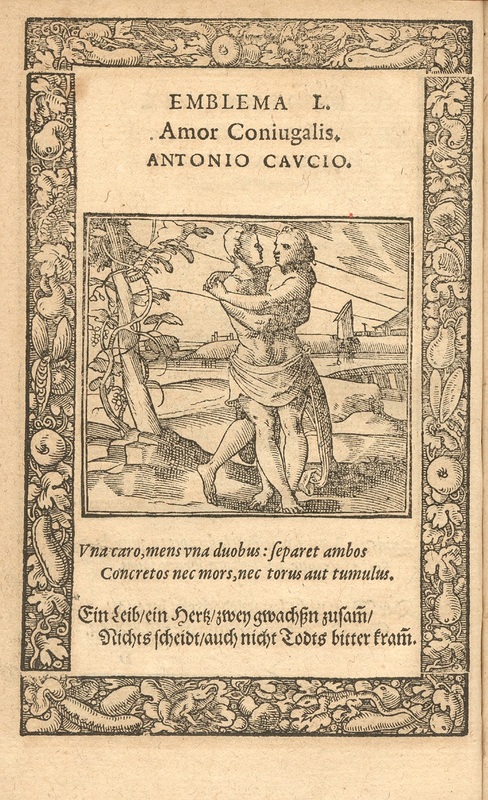

O son of Angles [English], and offspring of noble ancestors, has, then, a chaste maiden given you the pledge of her hand? Did you know how to win the love of a girl of high-born virtue, so that Juno, patroness of weddings, is binding you as equals, in matrimony? I congratulate you, and I pray all happiness for this fecund beginning. Let conjugal love grow, and let God, through it, make you twins. Let the Author in the sky keep you faithful to your marriage-vows, and let the desired act be celebrated…

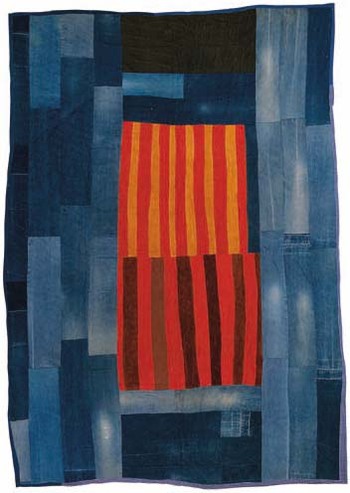

It is worthwhile to ask students to think about the discrepancies between the idealizing language ("let the desired act be celebrated") and the language that presents marriage as entrapment ("binding you"). There is an emphasis on sameness here: the married couple will be "twins" to each other, "equals" in matrimony. What is up with the picture depicting this union? Why do they look terrified? Why are they bound with chains? Why is there a snake that winds itself between the two couples? Why would being twins or equals be anything other than a good thing?

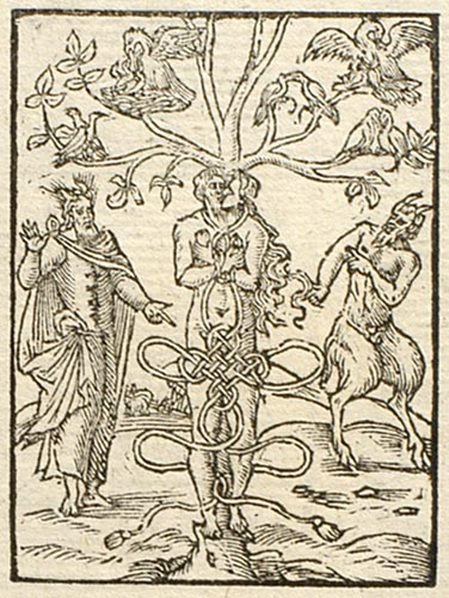

Let there be a Hermaphrodite of double shape in a single body; and let one face be a woman’s, the other a man’s. Let kisses then be given and taken as if with a twin mouth: which are the shared exchanges of sweet love. Let, on the one side, the Sage say that both are one flesh; but on the other (when they fight), let the satyr laugh that they are two. For the horned Jew commanded that they be two in a single flesh; this body is what the Androgyne expresses. [N.B. ‘the horned Jew’ refers to Moses. This epithet is based on a mistranslation of a Hebrew word and is not meant to be antisemitic.]

Then, let a fruitful TREE stand near, in whose branches many a bird shall sit…

FINALLY in the field far behind, a second scene takes place, a herdsman ploughing with two oxen. He does the equal work of shared labor and a like concern for making wealth grow. This is an apt symbol for well-grounded marriage in a wedding-bed blessed by law.

What does it meant to say that two people in a marriage--or even in love--are like a hermaphrodite? How does the term "hermaphrodite" register in our culture now, and do you think our connotations of the term are the same as they might have been when these emblem books were written and when Shakespeare was writing Antony and Cleopatra?

Myths of Hermaphrodites:

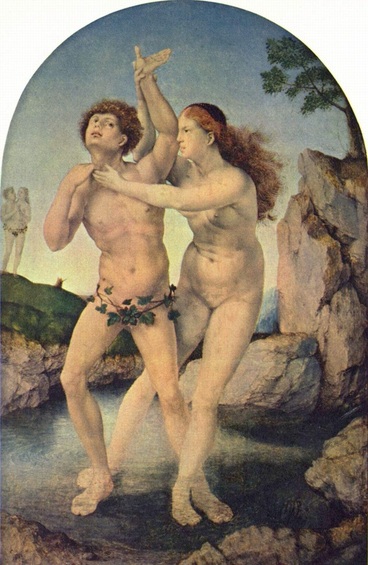

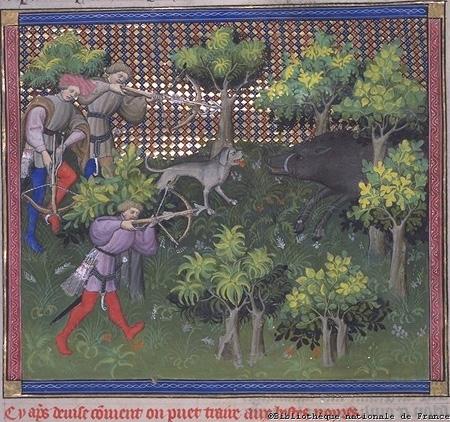

Ovid (a Roman poet) and Francis Beaumont (an early modern English poet and playwright) both have version of this myth, which you could assign for students depending on their grade level and ability. The poets tell the story of the female water nymph Salmachis who suffers unrequited love for the beautiful male hunter named Hermaphroditus. When she dives into the pool where he is swimming, she clasps her arms against his unwilling body and prays to the gods that they will make her embrace of him permanent. They do, and the two bodies fuse into one, both male and female.

Consider the following important question: what does it mean, then, that these emblem books draw on iconography and literary allusions that invoke this particular myth when they are describing marriage and heterosexual love?

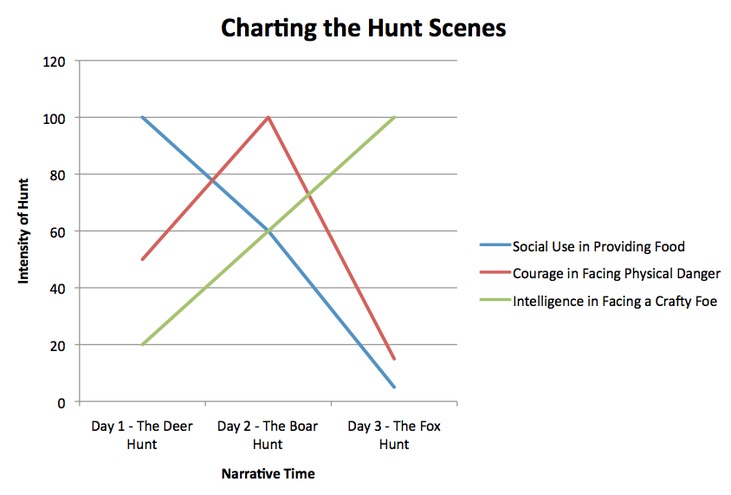

I think that this discussion will be useful to pair with Shakespeare's tragedy, especially around the repeated claims (made by the Romans), that Antony, once a phallic "pillar of the world" has lost his masculinity because of his love for Cleopatra. The threat of hermaphrodism lurks in the play when Caesar says that Antony "is not more man-like / Than Cleopatra; nor the queen of Ptolemy / More womanly than he." In other words, they are equally androgynous. Whereas Cleopatra and Antony seem to find this equality sexy (they even cross-dress in each others clothes), Caesar sees this equality as a sign of Antony's debasement.

My aim in this exercise is to get students to think about how--within the early modern period and the world of this specific play--desire itself could be seen as destabilizing heroic masculinity, even if the object of desire was the "appropriate" female object.

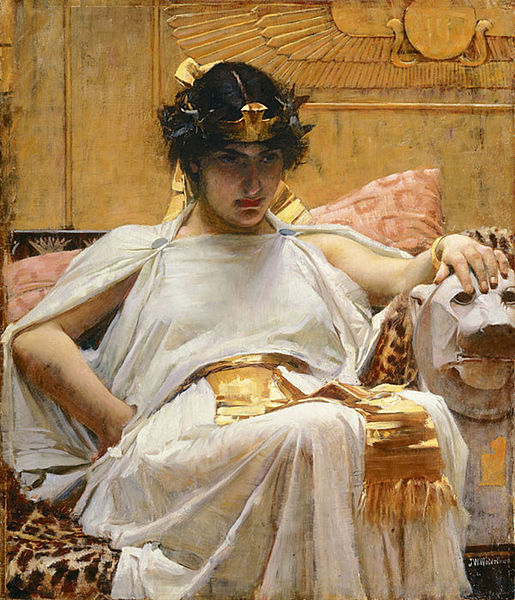

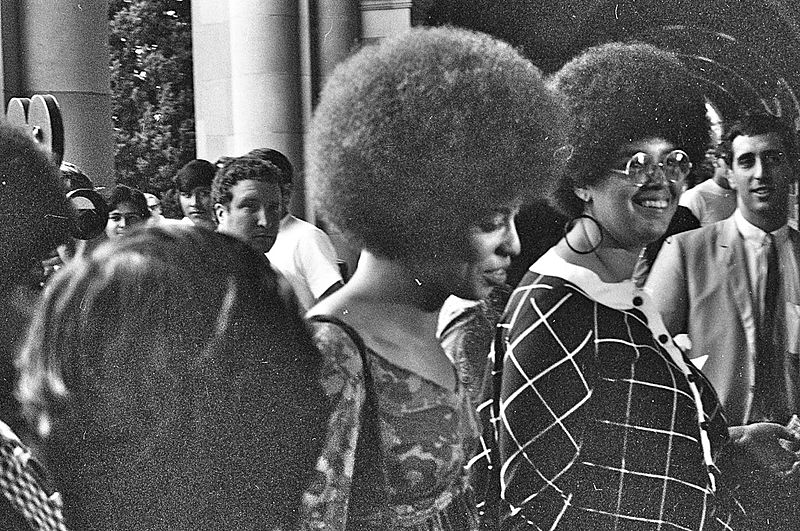

I mean THIS is what our culture associates with Cleopatra:

I want to emphasize that the 1963 Cleopatra is not just another example of Hollywood sexing up a story. On some level, "Cleopatra" as a cultural idea has become a signifier for sex, passion, and female authority--this cultural work has been literally hundreds of years in the making. Sometimes she's demonized for that (see the "wicked books" that the Wife of Bath's husband reads to her) and sometimes she's praised for that, but she has pretty statically remained a sex symbol since Roman times.

Antony getting to be with Cleopatra is like Joe DiMaggio getting to be with Marilyn Monroe, or Brad Pitt getting to be with Angelina Jolie. Cleopatra's pretty much the crème de la crème of women out there, and we could feasibly argue that Antony's ability to win her affection makes him more "manly" and not less. Why, then, does Caesar make the opposite argument?

What I hope that my students will get out of this discussion is the concept that ideas of masculinity and ideas of heterosexuality do not line up universally or naturally. If those two ideas line up now (so that we think of straight men as "real" men), then we have culturally constructed that association just as much as Caesar has constructed his ideas of masculinity and martial austerity. According to Caesar, there is only one way to be a "real" man and it is never in the bedroom.

Hopefully, though, seeing the diversity of images from the emblem books will help students to see that this militant austerity is only one conception of masculinity, and a pretty dangerous one at that. Antony and Cleopatra's love seems like a poignant and courageous protest against the gender norms of Rome, and their deaths seem all the more tragic to me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed