Beowulf is a really fun poem to teach because there are so many monsters in it. There are also, apparently, allusions to the poem in comic books and video games. Many of my students--often my male students--really enjoy learning about the "original" poem that they have only encountered obliquely in pop culture. I actually think it's a great idea to incorporate pop culture into your approach to the poem!

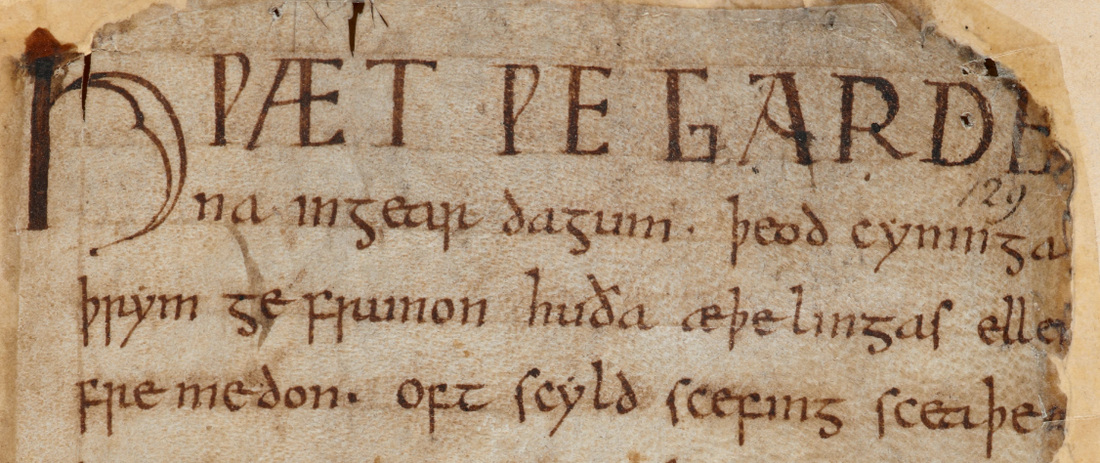

I recommend spending a minimum of three days on the poem, one per monster. The best edition to use is Seamus Heaney's translation in the bilingual edition with facing pages of Anglo-Saxon and modern English. I have a wonderful essay prompt that asks students to investigate the Anglo-Saxon through Heaney's bilingual translation along with the Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, which I will discuss in an upcoming post.

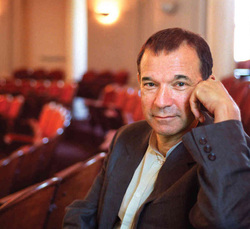

I also recommend that you send students to this site, where they can listen to Professor Michael C. Drout read the opening 11 lines of the poem out loud in Anglo-Saxon so that they have an idea of what "Old English" sounds like (because many people seem to think that Shakespeare "wrote in that Old English.") It's good to disabuse your students of this fallacy immediately.

Prof. Drout has a marvelous voice, and it's fun to peruse through the other poems from the Anglo-Saxon poetic record on his site, Anglo Saxon Aloud... it's definitely a site worth investigating!

Hwæt! wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum

þēod-cyninga þrym gefrūnon,

hū þā æðelingas ellen fremedon.

Oft Scyld Scēfing sceaðena þrēatum,

monegum mǣgðum meodo-setla oftēah.

Egsode eorl, syððan ǣrest wearð

fēa-sceaft funden: hē þæs frōfre gebād,

wēox under wolcnum, weorð-myndum ðāh,

oðþæt him ǣghwylc þāra ymb-sittendra

ofer hron-rāde hȳran scolde,

gomban gyldan: þæt wæs gōd cyning!

I approach the poem by talking about the ethos of Anglo-Saxon warrior culture filtered through the lens of Kristeva's notion of abjection. I ask my students to think about the poem as presenting evidence (through the various monsters that it presents to us) for what might have counted as "abject" in that society.

The abject confronts us, on the one hand, with those fragile states where man strays on the territories of animal. Thus, by way of abjection, primitive societies have marked out a precise area of their culture in order to remove it from the threatening world of animals or animalism, which were imagined as representative of sex and murder.

--Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horrors: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), pp. 12-13, emphasis in the original.

- The horror that the abject person provokes comes from a mixed sense of connection and distance. There is a sense of “this is what I came from” (love, or sense of connection) that coexists with “this is what I am no longer” (hate, or sense of distance) that creates horror, repulsion, and disgust because there is always a threat that this abject thing is what “I” could return to.

- For Kristeva, this process of rejection is something that happens at both the individual level and the collective level. The individual connects these feelings to the natural rejection of the mother (i.e. the process of growing up). The collective uses these feelings of rejection to establish boundaries between “good” and “bad”: the sacred and the profane, culture and chaos, us and them, etc. Society tries to delineate the boundary between “us” and “them” to create a sense of coherent identity in the group. Abject people get pushed to the margins or the boundaries because they create a sense of horror that the dominant group has more in common with the marginalized group than they would like to think.

- While twentieth-century French thought does not necessarily apply to tenth-century Anglo-Saxon culture (i.e., the psychoanalytic part about mothers and infants), the basic concept about an outcast group being reviled because of its similarities to the dominate group seems like it could be applicable to groups from many different cultures and time periods.

As we consider each individual monster, I ask my students: why would this monster be threatening to this society? If monsters are a sign of abjection, something to be shunned or outcast because they are a horrifying reminder of something a society would like to forget, then what is it about this particular monster that the members of Heorot don't want to have to see?

In order to talk about warrior culture, specifically in what is (probably) a tenth-century poem written by a Christian Anglo-Saxon poet, but looking back at the pagan past of seventh or eighth century Scandinavia, I turn to JRR Tolkien's famous essay, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics":

The monsters were the foes of the Gods, and the monsters would win; and in the heroic siege and the last defeat alike men and Gods were in the same host… the monsters remained – indeed they do remain; and a Christian [of Anglo-Saxon culture] was no less hemmed in by the world that is not man than the pagan [of Norse culture]...

We are in fact just in time to get a poem from a man who knew enough of the old heroic tales … to perceive their common tragedy of inevitable ruin, and to feel it perhaps more poignantly because he was a little removed from the direct pressure of its despair [through his Christianity]; who yet could view it with a width and depth only possible in a period which has in Christianity a justification of what had hitherto been a dogma not so much of faith as of instinct – a huge pessimism as to the event, combined with an obstinate belief in the value of the doomed effort.

-- J.R.R. Tolkien, Beowulf and the Critics, ed. Michael D.C. Drout (Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002), 65-67.

After the jump, I've included a set of discussion questions, some of which I have written myself and some of which I have culled from Fran Dolan and Margie Ferguson, professors at UC Davis who have shared their pedagogical strategies for the poem with me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed