First of all, there are many, many editions of this text available in print. It is important that you assign a text wherein the editors do not do too much damage to the original. I will get to this in a moment.

Next I suggest that you read the excellent essay "Captivity Narratives" by Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola in Teaching the Literatures of Early America, ed. Carla Mulford (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1999: 243-55), which does a great job of putting Rowlandson's text into context with other captivity narratives. I have never assigned this essay to my students, but I have drawn on it multiple times.

For my students at UC Davis, I have assigned Michelle Burnham's essay “The Journey Between: Liminality and Dialogism in Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative” (Early American Literature 28.1 [1993]: 60-75), which argues persuasively that Rowlandson's narrator speaks in two distinct voices throughout the text: 1) a victimized, spiritually fallen woman who regains her sense of devotional direction by submitting to a trial of faith and then writing a spiritual autobiography, and, 2) a tough, victorious survivor, and thereby a chosen child of God, who adapts to her situation by using strategies that include barter, manipulation, and the adaptation of certain “savage” characteristics of the Wamponoags. The reason that some editions--like the Dover Edition--are suspicious is that they edit out one of the voices listed above (usually the first voice, because this one is far more racist than the other).

Whether I am teaching college sophomores or high school freshman, I try to get my students to test out Burnham's provocative thesis and consider the implications of that reading. (I'm just sneakier about it with my high school students). Here are some of my basic strategies (all page numbers refer to the excellent edition collected in the Norton Anthology of American Literature):

So I took the Bible, and in that melancholy time, it came into my mind to read first the 28th chapter of Deuteronomy, which I did, and when I had read it, my dark heart wrought on this manner: that there was no mercy for me, that the blessings were gone, and the curses come in their room, and that I had lost my opportunity. (263)

But the Lord renewed my strength still, and carried me along, that I might see more of His power. (260)

Philip spake to me to make a shirt for his boy, which I did, for which he gave me a shilling. I offered the money to my master, but he bade me keep it; and with it I bought a piece of horse flesh… (268)

Being very hungry I had quickly eat up [my meat], but the [English] child could not bite it, it was so tough and sinewy, but lay sucking, gnawing, chewing and slabbering of it in the mouth and hand. Then I took it of the child, and eat it myself, and savory it was to my taste. (277)

I find it really useful and productive to ask students to try to articulate how they know when Rowlandson is speaking through the voice of the Patient Puritan and when she is speaking through the voice of the Resourceful Survivor. What are the stylistic markers that make it clear when she is using one voice or the other? The students are quick to note how the use of biblical citations marks the Patient Puritan in a really obvious way, but it takes some coaxing to get them to see the Patient Puritan as the more emotional of the two speakers. It's productive for them to see this narrative voice as an appeal to pathos, and to think then about how this text might function as a piece of rhetoric. Why this recourse to rhetoric? What "argument" is the Patient Puritan trying to make and to whom?

This leads into a discussion of how her two narrative voices present two worldviews that are sometimes at odds with each other. This is most apparent in the speaker's conflicting views of the Wampanoags.

Though many times they would eat that, that a hog or a dog would hardly touch; yet by that God strengthened them to be a scourge to His people.

The chief and commonest food was ground nuts. They eat also nuts and acorns, artichokes, lilly roots, ground beans, and several other weeds and roots, that I know not.

From there, we consider the larger text. What does Rowlandson think of American Indians and how does she present them? I reassure students that they may have contradictory ideas about this, mostly because Rowlandson seems to present the Indians in multiple ways. Are the positive and negative portrayals associated with her different narrative voices? Is she more likely to associate the Indians with evil, bestial, and cruel “nature” when she’s speaking in one, particular voice?

This discussion leads them to approximate Burnham's argument that the Resourceful Survivor is a sequential narrator and the Patient Puritan is an interjecting interpreter. The former reveals that there are quite a few Indians in the group who treat her with kindness and sympathy – sheltering her and feeding her even though they have nothing to gain. This narrator presents facts of the journey that we could interpret as her slow (but still incomplete) acculturation to Indian life. This narrator comes across rather like an ethnographer. The Puritan interpreter, however, totally rejects this reading. She consistently interprets any good thing that happens to Rowlandson as a sign of God’s goodness. The goodness of a select few Indians is not of their own doing, but is instead God’s work through them. This interpretation allows her to keep seeing the Indians as barbaric heathens worthy of scorn and contempt. This narrative voice presents a more orthodox Puritan view of the landscape as "the devil's Territory"--something that the Puritans have to resist as the people of God.

All of this leads to the question of why such a schism in the narrative voice exists at all:

- Does the Puritan interpreter exist to repackage her account wherein she subverts both traditional gender roles and Puritan orthodoxy as she struggles to survive? It is undeniable that this text allows for multiple views of the landscape, Native Americans, and women. Does this narrative technique of the divided speaker allow Rowlandson to slide heterodox ideas past moral gatekeepers of the Puritan community such as Cotton Mather (who contributed supplementary materiel to at least one of the early editions of Rowlandson's narrative)? Or is she attempting to control representation and shut down possible meanings about what happened to her and what she did during her captivity? If this is the case, then why not rewrite the narrative, editing out the Resourceful Survivor all together?

- Is this divided narrator an example of public and private voices? Does the interpretive Puritan narrator warn the colonists that God will scourge them through the Indians for their own moral backsliding? Does the sequential Survivor narrator, in contrast, present her own suffering as her personal struggle?

- Both of the above suggestions suggest that the sequential narrator, the Resourceful Survivor is the original narrator and that the Patient Puritan follows after. That need not be the case. Perhaps the split in the narrative voice is like a conversation that her present "redeemed" self has with her past "captived" self? In this reading, it is a dialogue between two voices instead of one voice attempting to speak over the other.

- Perhaps she sees herself as a possessing a divided subjectivity because her experience was so traumatic? Perhaps her partial acclimation to Wampanoag life is a form of Stockholm Syndrome?

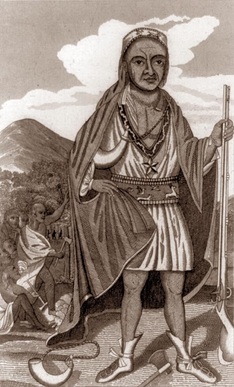

We wrap up our conversation by talking about the images that I've included at the top of this post and by talking about the popularity of this text when it was first published. The images are so similar to each other--why? What might that say? Why do you think that this story was the first trans-Atlantic "best seller"? Why would it appeal to both colonial and English markets?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed