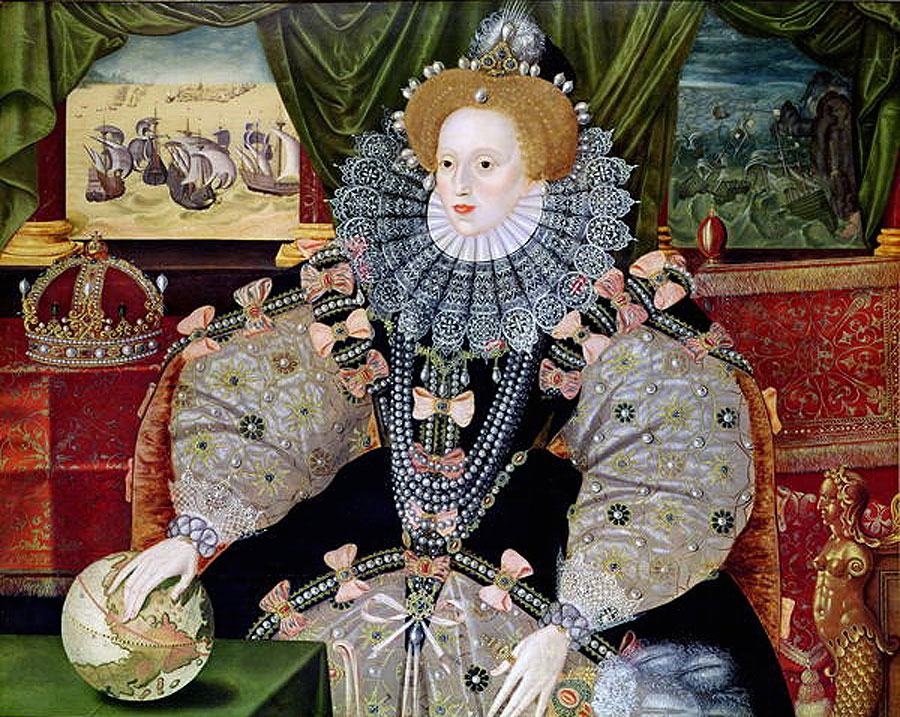

This blog post is part of my discussion about the course I taught, "Gender and Clothing in Shakespeare's Plays." It is a texts and contexts course, and the unit on Antony and Cleopatra is focused on the "tragedy" of female authority, particularly queenship.

In conjunction with Act 4, I assign the following contextual materials that build on our discussion of the episode between Radigund and Artegall in Spenser's Faerie Queene:

- A brief overview of the following myths (N.B., this website has many typos in it, but it is valuable because it synthesizes the mythic stories of Hercules from an impressive array of sources):

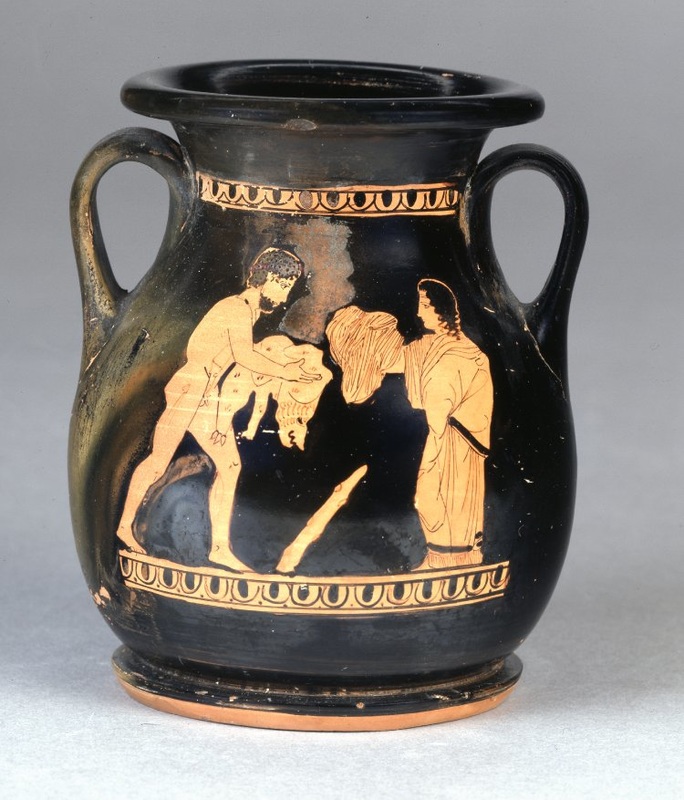

- Hercules and Omphale at this site.

-

Nessus and the attempted rape of Hercules' wife Deianira at this link.

- The death of Hercules at this site.

- Epistle 9 (Deianira to Hercules) from Ovid’s Heroides, translated by A.S. Kline (N.B., The Heroides (The Heroines), or Epistulae Heroidum (Letters of Heroines), is a collection of fifteen epistolary poems composed by Ovid in Latin elegiac couplets and presented as though written by a selection of aggrieved heroines of Greek and Roman mythology in address to their heroic lovers who have in some way mistreated, neglected, or abandoned them.)

I feel that this discussion of Hercules works especially well both because Spenser's episode from The Faerie Queene draws on the myth of Hercules and Omphale and because Antony was supposedly descended from Hercules as he acknowledges in Act 4. The following is a speech that he gives after the loss at the Battle of Actium:

Antony (to Cleopatra):

Vanish, or I shall give thee thy deserving,

And blemish Caesar's triumph. Let him take thee,

And hoist thee up to the shouting plebeians:

Follow his chariot, like the greatest spot

Of all thy sex; most monster-like, be shown

For poor'st diminutives, for doits; and let

Patient Octavia plough thy visage up

With her prepared nails. [Exit CLEOPATRA]

'Tis well thou'rt gone,

If it be well to live; but better 'twere

Thou fell'st into my fury, for one death

Might have prevented many. Eros, ho!

The shirt of Nessus is upon me: teach me,

Alcides, thou mine ancestor, thy rage:

Let me lodge Lichas on the horns o' the moon;

And with those hands, that grasp'd the heaviest club,

Subdue my worthiest self. The witch shall die:

To the young Roman boy she hath sold me, and I fall

Under this plot; she dies for't. Eros, ho!

Reading questions:

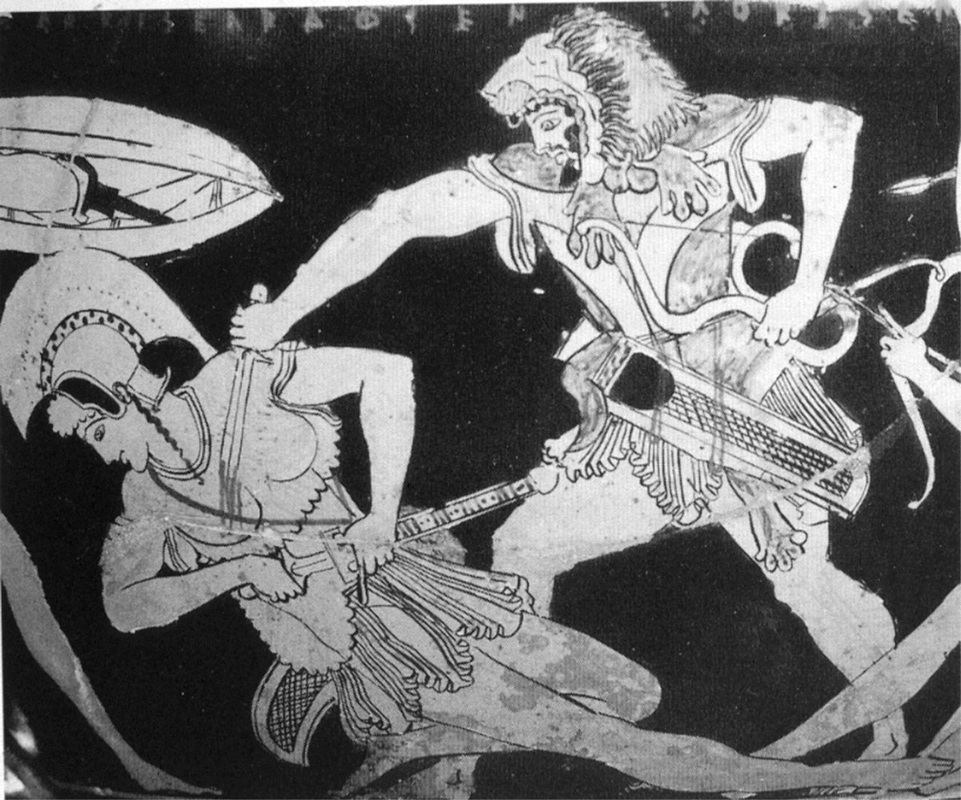

- How does this pelike construct clothing as dangerous?

- How does that accord with Ovid’s poem?

- In what ways are women associated with clothing, and is it the clothes or the women that undercut Hercules’ heroic masculinity?

- How does that echo in the episode about Artegall and Radigund from Spenser’s The Faerie Queene?

- How does that echo in Act 4 of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra?

Here is a passage from Ovid's Epistle that is pertinent to the discussion. Note that the poem is addressed to Hercules (aka Alcides), so all the "you" pronouns are meant as addresses to him. Deianira mocks him for having worn the female clothes of Omphale and for having deigned to do the woman's work of cloth-making.

Did your hand not draw back, assigned its smooth basket,

Alcides, conqueror of a thousand labours,

and did you draw out the thread with your strong thumb,

and was an equally handsome weight of wool returned?

Ah! How often, while your rough fingers twisted the thread,

your over-heavy hand broke the spindle!

Of course you’ll have told of deeds, hiding that they were yours…

Can you speak of [all your heroic deeds], marked out by Sidonian dress?

Shouldn’t your tongue fall silent curbed by your clothing?...

But why do I recall this? Written news comes,

rumour that my husband’s dying from the poison in his tunic.

Ah me! What have I done? What madness has my love caused?

Impious Deianira, why do you hesitate to die?

- Discuss the various ways that this passage echoes with both Spenser’s poem and Shakespeare’s play.

- Why would Hercules’ tongue be curbed by his clothing?

- Compare and contrast the two types of “bad” clothes that Hercules receives: one from Omphale and one from Deianira. Why does Omphale give him women’s clothes? Why does Deianira give him Nessus’ shirt? What are the various ways that women are associated with clothes?

- What's dangerous to Hercules: clothes or women?

I think that this is an excellent place to consider the passage from Act 2 wherein Cleopatra reveals that she and Antony would cross dress as each other as part of their debauchery/erotic play:

That time,—O times!--

I laugh'd him out of patience; and that night

I laugh'd him into patience; and next morn,

Ere the ninth hour, I drunk him to his bed;

Then put my tires and mantles on him, whilst

I wore his sword Philippan.

The rest of the class we spent on following passages: 1) Enobarbus' last words, 2) Antony's famous monologue wherein he mournfully assesses the loss at Actium as a loss of his own identity and a betrayal by Cleopatra, and 3) Antony's last words. In many ways, these three speeches all highlight the loss of heroic identity that has defined Antony. The following discussion questions help students to work through this theme that dominates Act 4.

- How, exactly, does Enobarbus die?

- Can Antony will himself to die? What does it matter that Enobarbus can will himself to die, but Antony cannot?

- Notice the last word that Enobarbus utters. What does Cleopatra ask Mardian to tell Antony is the last word that she utters (see 4.13 and 4.14)? What does it matter that Enobarbus actually does utter the word that Cleopatra pretends is her last word?

- In some ways Enobarbus has the ideal death that both Antony and Cleopatra desire: he simply dies of a broken heart (as Antony wishes he could do) and he dies demonstrating his love for Antony (as Cleopatra wishes to do). Why does Shakespeare give him this idealized death?

- Why do you think Antony spends so much time talking about things that dissolve like clouds, reflections, and bodies that cannot hold a shape? What, exactly, is dissolving in 4.14?

- What do we make of his later claim that Cleopatra has robbed him of his sword? And that he says so in front of the Eunuch?

- What do we make of his immediate grief, even after he was so sure of her betrayal? Does he not really believe that she has betrayed him, or is he (like she) made of infinite variety?

- Compared to Eros and to Enobarbus, doesn’t Antony rather botch his suicide? What is significant about that? Is this the final, undignified failure that he must face?

- He asks a character named “love” to stab him in the back. What is significant about that? But “Love” doesn’t actually stab him in the back. Significance?

- Cleopatra’s words to Antony once they have him hoisted up to the monument play on the sexual pun, “die.” What’s up with that?

- Why does he say, “The miserable change… I can no more"?

- What is triumphant in Antony’s last speech and what is defeated? Compare these last words with Enobarbus’ last words.

- So it’s the end of Act 4 and Antony is dead, but Cleopatra lives on. What?! Who is this play really about? Why doesn’t this end like Romeo and Juliet, with Cleopatra killing herself immediately?

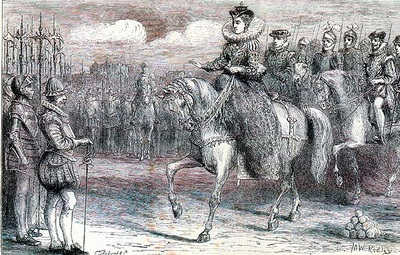

This strategy for teaching Act 4 went over extremely well in the classroom. Students were very interested in the connections between Antony and Hercules, but they were even more interested in the connections between Cleopatra and Omphale/Deianira. Omphale and Radigund worked well with each other, and Deianira complemented some of our earlier discussion of Queen Elizabeth.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed