What's good about structuring the pedagogy of the play in this way is that it asks students to think about the categories of dramatic genres, to attempt to construct a definition of tragedy and comedy at the very least. Some of my students don't have a very strong concept of either of the two categories, but they are especially limited in how they think about comedy. They tend to define comedy simply as "funny," but that really isn't a good enough definition for Renaissance drama.

I always implore my students not to read Sparknotes for this play because it has a surprise ending, and they will not want to read any "spoilers." Surprisingly, they seem to honor that request once I give them an intrinsically motivating reason to read the play on its own terms. As long as they play along, I end each class period with the question: "How do you think the play will end and why?" This question is not only useful for talking about genre, but also a good way to build suspense within our reading community.

In the following post, I will both give working definitions of the genres and also suggest methods for getting your students to define the genres and use them in their analyses.

Tragedy

A play or work characterized by serious and significant action that often leads to a disastrous result for the protagonist. Until the 1700s tragedies were usually written in poetry (instead of prose) so as to achieve an elevated and dignified literary style. Their tone is sober and weighty. Although the central character comes to a tragic end, tragedies usually conclude with a restoration of order and an expectation of a brighter future for those who survive.

Traits of the genre:

- The protagonist of the tragedy, called the tragic hero, is usually a person of high rank or great importance, like a king or a warrior. The Greek philosopher Aristotle argued that a tragic hero should be neither superhumanly good nor evil; rather, the hero is likeable but flawed. Modern tragedy does not insist on the high social position of the protagonist, but does insist on characters that are neither extremely good nor extremely evil.

- Aristotle also claimed that a tragic hero suffers a change in fortune from prosperity to adversity as a result of a mistake, an error in judgment, or a frailty, called hamartia. For Greek tragedy, this mistake or flaw in judgment is not necessarily related to a character flaw, but can instead be a result of fate. Conversely, Shakespeare and other Elizabethan tragedians often linked the protagonist’s tragic flaw to his/her best trait, so that the same trait that makes a character noble causes the character’s downfall. For example, Othello’s passion both enables his love for Desdemona (and endears him to the audience) and makes him vulnerable to jealousy. Hamlet’s incredible desire to acquire knowledge makes him seem to be a rational and fully rounded character, but it causes him to miss his chance for equitable justice.

- Tragedies almost always end in death.

- The focus of the tragedy is on the significance and interior world of the individual and his or her impact on the community.

Aristotle wrote that tragedy should have the effect of catharsis, which is usually translated as “purgation” of “purification.” What he meant by that is widely disputed, but a common summation is as follows: the play first raises the emotions of pity and fear. Member of the audience pity the hero (because he is great and noble) and fear lest they encounter a fate similar to the hero’s (because they can recognize themselves in his flaws). The artistic handling of the conclusion, however, releases and quiets those emotions as order is restored and the hero faces his destiny with fortitude, thus affirming the courage and dignity of mankind. Moreover, the member of society that has sinned or unconsciously created a problem is removed from the society; thus, both the world within the play and the outside world of the audience feel purged or purified.

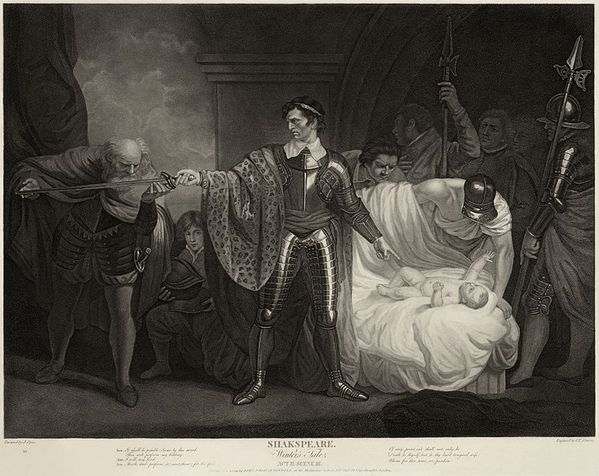

- Who's subjectivity does the play examine in these acts? What do we learn from this close attention paid to Leontes' inner world? Is he a tragic hero? If so, is he a tragic hero in the sense that Aristotle gives or is he more like some of Shakespeare's other heroes? What is his tragic flaw and is it a perversion of a "good" impulse that makes him great? How do you know and why does that matter?

- Leontes reveals his jealousy in 1.2: there are two ways to read this: either his jealousy is totally out of the blue, or he is already suspicious. What way would you play it? What textual evidence supports this reading? What evidence does he point out in this scene, and what other circumstantial evidence exists? Unlike Robert Greene’s Pandosto (Shakespeare’s source text), where the narrator tells us that Hermione is completely innocent, Shakespeare plants some circumstantial evidence that Hermione may be guilty. What does he gain by even temporarily making us question Hermione along with Leontes?

- Who is Mamilius and how does the character take on symbolic meaning? Is he a mama's boy or a daddy's boy, and why does that matter? What kind of stories does he like to tell? In Act 3, Leontes imagines that the boy is sick because he is ashamed of his mother’s adultery. Paulina later says his heart broke because his father accused his mother of something so bad. He dies immediately after Leontes’ proclamation that the oracle is a lie. Are we supposed to understand that he dies because of Leontes’ mental and spiritual corruption and not because of his mother’s physical corruption? Why do you think he dies?

- Who is Paulina, and why does Leontes seem kind of afraid of her? Why does Leontes feel kind of afraid of women and servants in general?

- Is Hermione's trial a fair one? How do you know, and why does it matter?

- Go back to the "aims" of tragedy. Have they been achieved in any way by the end of Act 3?

- How do you think this play will end and why?

Transition from tragedy to comedy

Consider also that there were bears in early modern London (specifically brought in for the sport of bear baiting), and that it is technically possible (albeit highly improbable) that the players at the Globe could have used a live bear at this moment. How would the genre read if the prop bear is truly frightening, or if there were a real bear on stage?

Comedy

The defining trait of comedy is a happy ending. Comedy is not necessarily humorous, but often can be. It is marked by a celebration of life, and the tone is lighter than that of tragedy. Its style is less elevated and is often written in prose with a focus on wit and wordplay. Comedy generally deals with ordinary people in everyday activities, but the events of comedy often include exaggerated and unrealistic circumstances. Characters break rules, reverse normal relationships, and get into bizarre situations; however, from all this disorder, comedies end with restoration of order and often conclude with a dance, marriage, or celebration of some kind symbolizing harmony and happiness. Comedy emphasizes the physical or sensual nature of humans, and often has sexual undertones.

- Stock characters: In romantic comedies, there are certain characters that seem to be “types” instead of fully rounded characters. Generally, romantic comedies focus on two young lovers who face obstacles to fulfilling their relationship. Although the obstacle can be any number of things (parental opposition, competing lovers, economic differences, separation because of war or travel, or just plain bad luck) the most common obstacle is that of an older, patriarchal "blocking" figure.

- The young lovers get together in marriage at the end, and we know that they will make babies eventually and ensure a new generation. Thus, the focus of the comedy is on the survival of the group rather than the interiority of a single protagonist.

Effects or aims of comedy:

Because the blocking agent is so common, comedy has been thought of as responding to generational conflict. Inevitably, the marriage at the end of the comedy signifies that a new family has been established to replace the older generation in preeminence; as such, comedy seems like it could be disruptive to the status quo. Other critics argue that comedy reaffirms the status quo. The fact that the topsy-turvy carnival world is straightened out and put back into an ordered system suggests that, though the head of the family may have changed, the basic power system within the play remains the same. Critics think that the aim of comedy is to purge the audience of melancholy, or sadness; to reaffirm that life goes on.

- 1.1 and 4.2: Compare this scene to the opening scene of the play. Notice that we are still facing similar conflicts: two kings have an uneasy tension between them and too much depends on one of their sons. Does Act 4 replay the same problems of the first three acts but with a new genre? Notice the major difference is that a king and a courtier are talking (on the same team now), and Polixenes is basically using Camillo as a spy. He trusts him absolutely, whereas Leontes trusted no one. What enables the shift from tragedy to comedy… trust, time, youth?

- Who is Autolycus and why does he use so much clothing imagery? What does clothing do as a symbol in this part of the play?

- First compare and contrast Polixenes in 4.2 to Leontes in Acts 1-3, then compare and contrast Florizel with either of the two kings. Look back to the "aims" of comedy, above. Does Florizel overturn or uphold the status quo?

- How do you think this play will end and why?

Romance and/or Tragicomedy

A new genre that formed during the time Shakespeare was writing. It was first theorized by a contemporaneous Italian writer, Giovanni Battista Guarini, who argued that tragicomedy was not a sloppy hybrid of tragedy and comedy, but a praiseworthy, deliberated constructed “third kind.” The reason why Guarini considers tragicomedy so highly is because it mirrors life more accurately (by mixing the profound and the profane) and because it purges the audience in a more tempered way; tragicomedy avoids both the horror of tragedy and the raucous laughter of comedy. He sees the shift from tragedy to comedy as mediated by the author. This shift is brought about by a “credible miracle,” that reverses the trajectory of the play. The tone and style of tragicomedy are serious, and the expected outcome is disaster or death; however, by grace of the credible miracle, the disaster is averted and order and harmony prevail. The genre thus provokes suspense and then relief in the audience.

Romance:

In general, the term "romance" refers to narrative stories (i.e., not plays) about the marvelous adventures of a chivalric knight, often of super-human ability, who goes on a quest. Romances often rework legends and fairy tales and traditional tales about Charlemagne and Roland or King Arthur. These tales are deeply imbued with dreamlike and magical elements. Shakespeare's late plays have been tentatively called "romances"--a term that Shakespeare himself would not have used--since the publication of Edward Dowden's Shakespeare: A Critical Study of His Mind and Art (1875). The plays share certain characteristics such as a redemptive story arc, the reunion of long-lost family members, magic and supernatural elements that sometimes approach deus ex machina, and lush sets (associated with the court masque). Even more than the tragicomedy, the aim of the romance is to fill the viewer with a sense of wonder. Romance is marked by a nostalgic or prophetic vision of a better, golden world.

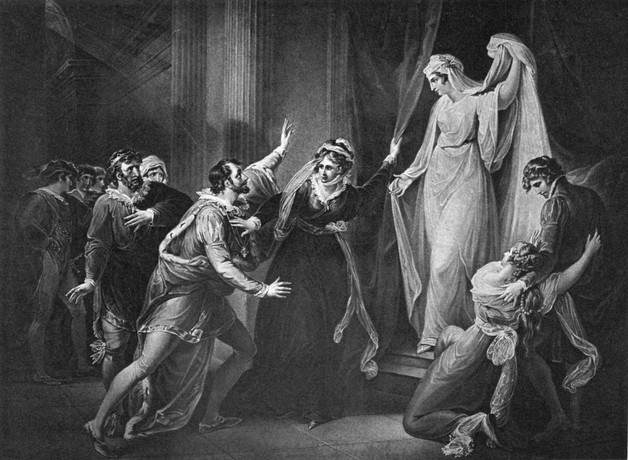

- What was your emotional reaction to the following parts of this act: 1) the creepy discussion of the ghost that Paulina and Leontes imagine together, 2) the fact that Leontes and Perdita recognize each other as lost father/daughter offstage and that their reunion is related to us through exposition rather than shown to us directly, and 3) the statue scene. Were you feeling suspense and relief, confusion and wonder, or some mixture? Why? What specific diction provoked these feelings? Point us to the words that affected you most.

- In Shakespeare's source text, Hermione really "is" dead. It was a popular prose romance that audience members might very well have known, and so they would have probably been surprised by the statue scene. Why do you think Shakespeare changes the ending? What kind of impact does that have on the plot or on the specific affect produced in the audience members? If we have time, I like to bring in Ovid's tale of Pygmalion too.

- Did you guess that the ending would go down like this, or that some version of this would happen (i.e., there would be some sort of improbable ending)? What were the "clues" that helped you to see that, or what were the obstructions that prevented you from guessing? Looking back on the entire play, what generic clues are there?

- What is the "credible miracle" of the play, or is the miraculous not really credible but rather magical? Why does that matter? Does it make any difference if we look at this as a tragicomedy or as a romance?

- How has Leontes changed (if at all), and does he merit forgiveness? What kind of world view do we see at the end of the play?

In the past, co-teachers have told me that they thought their students walked away from the play feeling like it was a dud in comparison with some of Shakespeare's other works. I think that this approach allows students to see the play's genre as a game that Shakespeare is playing, that he's continually revising the genre to thwart the audience's expectations and, in doing so, he's asking us to think about what we want out of endings. To me, this has been a great key to opening up the play to students.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed