I recommend spending 2-3 days on the book. For older students, 2 days is sufficient but younger students really do need an extra day. The book can be divided into two by dividing the reading at the moment that the Coramantian prince, Oroonoko, arrives in Surinam as a slave. The book can be divided into three parts by assigning a section on the oriental romance (up through the point where Oroonoko's wife, Imoinda, is sold into slavery), a "middle passage" that shows both how Oroonoko is tricked into slavery and his initial period of enslavement wherein he and the book's narrator have a series of adventures in the New World, and then a remaining passage that focuses on the moment that Imoinda's pregnancy provokes Oroonoko into leading the slave rebellion, and all the tragedy that unfolds after.

Big Questions:

One of the major questions about this book is whether or not it's abolitionist. On the one hand, the narrator condemns what happens to Oroonoko and Imoinda as a horrible crime against humanity; on the other hand, she seems to be preoccupied with the fact that they were royalty in their own country. In the second reading, the problem is not slavery per se but the fact that their royal sovereignty was subjected to "unnatural" slavery. At each stage of the reading, ask your students to consider the narrator's position on slavery in general and in relation to Oroonoko's specific enslavement.

In addition to close reading, I have found that the following methodologies have been really useful for opening up the book for an investigation of its racial politics:

James II of England

James II of England It's good to situate the book in relationship to British politics at the moment of its publication in 1688, the same year as the Glorious Revolution, when Catholic King James II was forced to abdicate because Parliament wanted to put his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange into power.

Behn was an outspoken supporter of James, and she objected to the moves being made against him to limit his power. Oroonoko can be read as a paean to monarchical power, and therefore as a critique of the people who would curtail royal the royal prerogative.

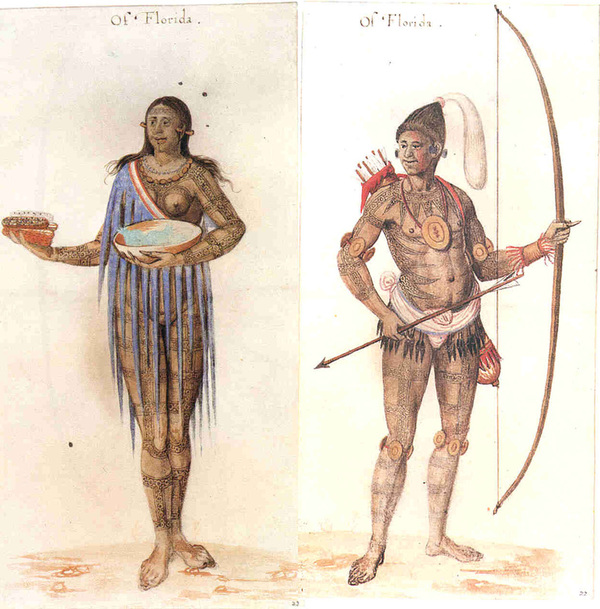

As Catherine Gallagher notes in her Bedford Cultural Edition of Oroonoko, the first part of the book is in the genre of the "Oriental Romance," even though Oroonoko lives in West Africa in a country called Coramantien (modern day Ghana). In this genre, a nasty, terrible, despotic king kidnaps the virginal, beautiful, virtuous love interest of the hero. The hero has to break into the harem where his lady is held captive and help her escape. This genre is especially associated with "oriental" spaces of the near (Turkey), middle (Arabia), and far east (India). Students can recognize this narrative from modern-day pop culture, especially Disney's Aladdin.

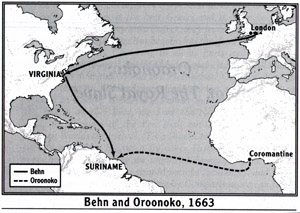

Geomapping:

Using maps to consider the spaces of the story is actually a great way to conceptualize how Behn is establishing certain key spaces in her story, while also implicitly including England in her discussion.

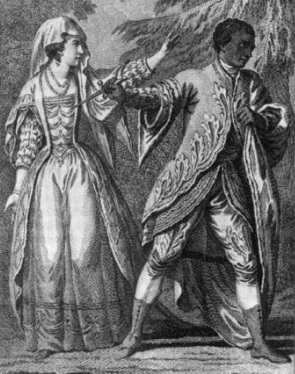

Although Behn wrote many plays during her lifetime, she chose to write Oroonoko in narrative prose instead of as a play. It was, however, almost immediately adapted into dramatic form by Thomas Southerne, with a major change to the original story: In Southerne's version of the play, Imoinda is white. How does that change things? Obviously, Southerne would be creating associations between Oroonoko and Othello, but what does that do to the way that we see Imoinda as a character?

I think it's especially important to consider reception theory too. Behn has become an important figure of study because of Virigina Woolf's praise of her in A Room of One's Own and because of the important work of feminist scholars in the 1980s to include more women writers in the literary canon. But for a very, very long time, Behn was a marginalized object of study despite her popularity during her lifetime. In many ways, Thomas Southerne's version of the story--the one with a white Imoinda--is the one that people knew for centuries. Why was this version received better--because of the gender of the author or because the "desirable" black woman was threatening to the original audience?

This old dead hero had one only daughter left of his race, a beauty, that to describe her truly, one need say only, she was female to the noble male; the beautiful black Venus to our young Mars; as charming in her person as he, and of delicate virtues. I have seen a hundred white men sighing after her, and making a thousand vows at her feet, all in vain, and unsuccessful. And she was indeed too great for any but a prince of her own nation to adore.

Jones' Masque of Blackness (1605)

Jones' Masque of Blackness (1605) What I want to do is ask students to think about Behn as negotiating a space between Bandele and Southerne in terms of Imoinda's character, and to think about what that might mean. In all three texts, what kind of character is Imoinda? Compare and contrast the narrator in Behn's text to Imoinda: how is each character preserving Oroonoko's legacy? Are they in competition with each other? How is femininity constructed in these various iterations of Imoinda's character and in Behn's narrator?

One last note:

I recommend that you skim through Jack Lynch's annotated bibliography of Behn criticism. It's out of date, but it is still useful for catching up on some of the early debates about Behn's text.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed