In order to do this, it is necessary to define "feminism" for your students. It's useful to talk to them about the history of movement so that they can recognize the great gap of time between when Chaucer was writing and when the political feminist movement(s) took place, and so that they can tease out the ways that Chaucer either approaches or fails to approach the goals of the feminist movement in his prologue and tale.

First wave – suffrage. Turn of the century in Europe and North America. Elizabeth Caddy Stanton, etc. The early feminists bravely fought for women’s right to vote in Western civilization.

Second wave – 1960s, especially in France and North America. Women like Irigaray, Kristeva, and Cixous in France and Freidman and Steinem in America wrote about the way that a masculinist Western culture attempted to repress women’s ability to speak, write, work or even really exist in the public sphere.

Third wave feminism – 1980s to the present day. The Second wave feminists were criticized as being too “black and white” in their thinking (“bra-burning man-haters”)… Third wave feminism is supposed to be both kinder and more nuanced philosophy. Some general characteristics of it are as follows:

- More nuanced thinking about the differences between women. Does not assume that the problems faces suburban wives in USA are the same problems facing fifteen-year old girls in Uganda.

- More nuanced in the relationship between men and women to avoid the “man-hater” stereotype that became associated with second-wave feminism. Although there were undoubtedly some man-haters in the second-wave feminists, I want to stress that the writing of the feminists is not angry at real-life men but at a “masculinist” culture: a culture that systematically prevents women from having equal opportunities to men. Nonetheless the stereotype exists, and that is one of the reasons that “feminist” is sometimes thrown out there like a dirty word. If you have that misconception of feminism, discard it now.

- More interested in the idea of “having it all.” Women who did not want to conceptualize the world in terms of a choice between a life in the public sphere that included fulfillment in terms of work and career and a life in the private sphere that included fulfillment in terms of family life.

In my time teaching, I have learned that it is very important to drive home the following point to your students: feminism is NOT saying that women are better than men. It is NOT saying that women deserve more power than men, even in marriage. It is not attempting to take the current power structure and simply invert it so that women are on top; rather, it is attempting to abolish a hierarchical structure, and replace it was an egalitarian one.

Then, I ask students to consider the following BIG questions, which we consider over the course of our entire unit:

- Does this text suggest that women should have the right to an opinion on marriage and that they should be free to express it?

- Does this text suggest that women’s thoughts about marriage are as valid as men’s thoughts about marriage?

- Does this text make women’s experience in marriage seem to be a valid counterpoint to the authority of the male writers who argue that virginity is holier than marriage?

- Does this text make the Wife seem monstrous… a grotesque expression of womanhood, something to be mocked and shunned? If so, does this portrait completely undermine the Wife’s argument about female expression and authority through and/or in marriage?

Advanced students can read ll. 1-502 in a single day, but for younger or less advanced students, you will probably want to split that up so that they read ll. 1-192 on the first day (the opening discussion of experience and authority) and ll. 193-502 on the second day (the discussion of her first four husbands).

Also advanced students can probably handle ll. 503-1263 in a single day, but younger students would do well to slow down and read ll. 503-856 (the discussion of Jankyn) and ll. 857-1267 (the Tale) on two separate days.

Both the language and the concepts are hard, and benefit from slow, careful reading. In the post below, I will share my strategies for opening up the Prologue and the Tale to student discussion.

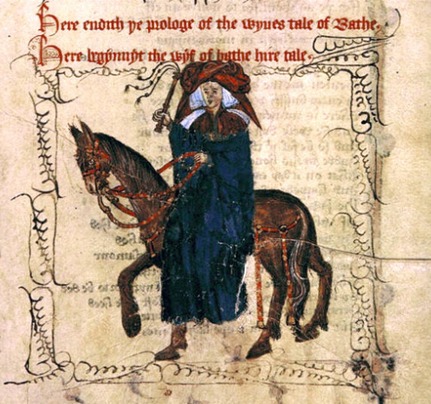

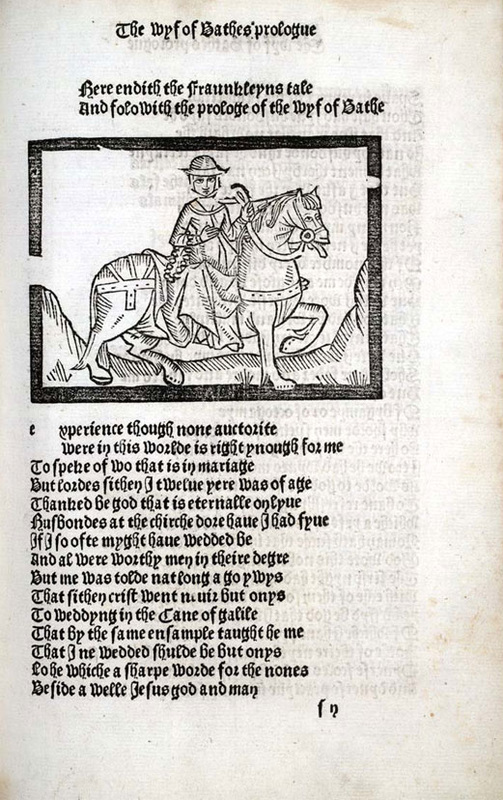

The Prologue

What can we glean that the authorities are saying? Against whom does she position herself?

- That people should not remarry because it is a sin: bigamy, adultery, etc.? (lines 9-34)

- That women especially should not remarry? (lines 35-46)

- That male-authored “learning” about marriage through the bible is somehow better than her own “learning” through actually participating in marriage? (47-50)

- That marriage is bad because only virginity is holy? (65-120)

- That “members of generation” were made primarily for purgation of urine and to tell males from females? (121-140)

- That sex itself is bad? (155-159)

- That men aught to have complete dominance over their wives? (160-168)

If there is time, I like to discuss the ways that the Wife appropriates the methods of biblical exegesis that clerks practice. I give students a handout on Ephesians 5 and 1 Corinthians 7, and then ask my students to think about what it means that she both quotes and misquotes the bible.

The Wife is masterful at taking biblical passages out of context. To a student who is somewhat familiar with the bible, these passages will sound vaguely “right” but the Wife's excerpts are actually arguing something different from what the biblical passages say in their entirety. The Wife does this to take a diametrically opposed stance to what most monks, priests, and clergy were saying about marriage and about women when they were using the exact same rhetorical strategy and quoting the exact same passages of the bible. The effect at the time would have been startling… and perhaps it still is today. In adopting this rhetorical strategy, the Wife draws attention to the power of preachers to shape someone’s larger, total understanding of the bible, particularly the types of relationships between men and women that the bible advocates. She's co-opting the clerks' text and their rhetorical tools.

What does this opening do for our understanding of the Wife’s character? What kind of person does she seem like here?

The Wife provokes the anger of the Pardoner, who sarcastically calls her a “noble preachour” (171). As a mock preacher, she is assuming a role normally reserved for men: “A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet” (1 Timothy 2:11-12). She, however, casts aside this criticism very gently by saying that her intent is only to play (198).

Where does the wife seem playful and where does she seem serious? Are there places in her prologue where she seems angry, sad, flirtatious, funny, etc?

There is then a long, long passage (her discussion of her "good" husbands and also the first of her "bad" husbands) wherein she seems to be an amalgamation of every bad quality that men fear in women: gold-digging, lying, cheating, manipulative, loud-mouthed, unruly, etc. She also falsely paints herself as the "victim" of their drunken, anti-feminist tirades in order to win pity from them that she doesn't deserve (although she uses language from real antifeminist books, so the language is convincing to them). What do you make of this portrait? Why does Chaucer do this? Does this section perhaps undermine the presentation of the wife that we saw as she was positioning women against clerks? Why or why not?

The OED defines the word "dangerous" according to the following definitions:

Difficult or awkward to deal with; haughty, arrogant; rigorous, hard, severe (current at the time of Chaucer’s writing, c. 1386)

- Reluctant to give, accede or comply (current c. 1386)

- Fraught with danger or risk; causing or occasioning danger; perilous, hazardous, risky, unsafe (first record of this sense is 1490, this is the current sense of the word)

What does this troubling passage do for our understanding of the Wife’s character?

- Does it mirror the earlier passages, wherein she appeared to be in total control of her husbands, but was only posing? Does it soften the anti-feminist pastiche?

- Does it instead make her seem like an abused housewife, and perhaps portray another side to a well-rounded anti-feminist portrait (i.e., that women "want" to be dominated and hurt)?

- Does Chaucer seem to give voice to real sadness here that her husband’s anti-feminist literature produces real violence against women?

This point perhaps goes to the ideas inherent in the second wave of feminism: in the long scope of history, women have not been permitted to enter the public sphere through their writing. The Wife seems to make a similar argument, that her culture has silenced women's voices and only allows one side of the story to be told: that the male gender is superior in virtue and that a clerical life of virginity is better than a secular life of marriage.

The section from 720-793 recounts the anti-feminist stories and proverbs that Jankyn reads to her from his book. This section balances out all the reported speeches that her “good” husbands supposedly tell her in their drunkenness. Whereas before she postured like a victim of verbal abuse to arouse shame and guilt in her husbands with the intention of using that guilt to control them, now the wife really is a victim of her husband’s verbal abuse.

- Why does Chaucer include this section? How are the charges Jankyn lays against women perhaps more damning than the charges that the Wife pretends to have suffered at the hands of her "good" husbands? It seems to me that in this section, Jankyn asserts that women are not capable of love, and that they have no worth. The sections above don’t paint women as violent things to be shunned as much as it paints them as manipulative creatures to treat with suspicion... Do you agree? Or are they equally as bad?

- Why is her heart filled with woe and pain at this diatribe whereas she was filled with a type of glee at her husbands’ complete willingness to believe that they would have actually said all the anti-feminist things that she claims they said?

The tale of the fight they have over the book: ll.794-828; Now this entire prologue seems to be about texts, sources, books, and clerks. It is about who gets to write, who literally puts words in other people’s mouths, and who is not allowed to write. It is perfectly fitting that the fight is over a book and not, for example, over clothing or land. How might the escalation of violence over this book be a metaphor or a symbol? How do the two get over the fight, anyway? Is this realistic? Is it a fantasy or a nightmare?

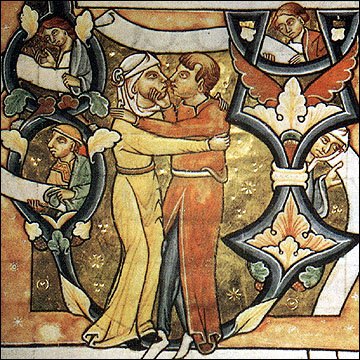

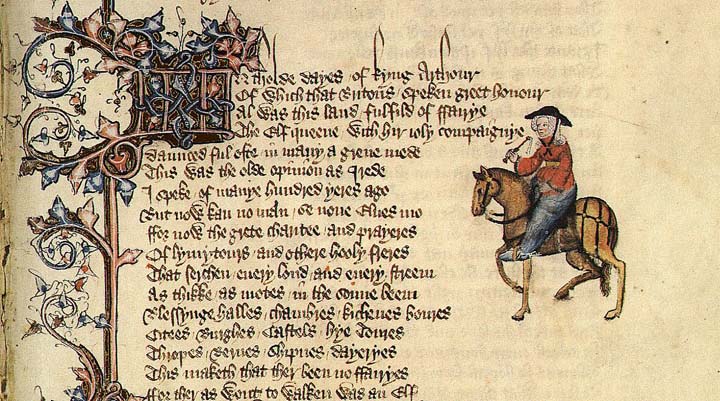

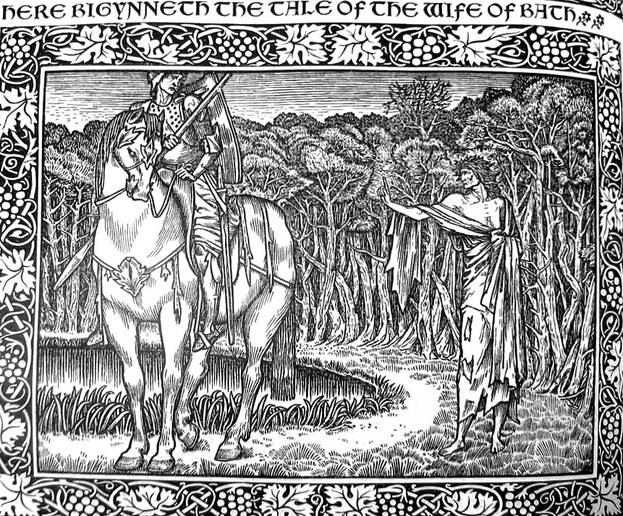

The Tale

- The reason that they are call “romances” is because the first ones in the genre were written in the vernacular (French, Spanish, and other romance languages) instead of in Latin. Even though Arthur is a figure out of British legend, stories about him were popular in continental Europe as well.

- They usually deal with quests, and often a knight goes on a quest with the intention of either winning or rescuing a lady. Because romantic love was a common theme in these stories, we developed our word romance (in its modern sense) from these stories.

- In any case, the quest is a type of journey he undergoes to learn about virtue and defeat vice. There is a definite sense of good and evil in the world, a kind of black-and-white mentality.

- The monsters the hero fights are oftentimes outward projections of inward struggles to remain virtuous (i.e., a hero lies because he fears that he will die when he is put to the trial, and then all of a sudden he encounters a sly fox in a hunting scene; the “sneakiness” associated with the fox is something the hero has to encounter in his own psyche). The metaphorical and allegorical nature of romance allows the genre to explore the inner psychological or spiritual states of the heroes.

- The stories dealt with chivalry. Arthur’s court had a reputation as the most-famous center of chivalry in pre-history Europe.

- Arthur supposedly existed during the brief period of time after the Romans left England but before the Anglo-Saxons took over. He was supposedly a “Briton,” a member of the original people inhabiting the British Isles. Stories about Arthur, told after the Norman invasion, look far back in time (~900 years). The genre of romance is always a nostalgic form that looks back to golden days.

- In most cases, romance as a genre is akin to fairy tales: the protagonist is not a god or a demi-god, but rather a human being who has strength, determination, or virtue that is beyond the scope of most humans. He encounters mystical forces or monsters. This genre is not meant to be realistic.

- Perhaps to undermine the Wife’s thesis? The ending of her prologue reads a little bit like a fairy tale (and then we lived “happily ever after”). Does the genre of her story re-enforce a reader’s skepticism that giving women “mastery” can somehow bring about happiness in marriage?

- Perhaps to nuance the Wife’s thesis? Does the Hag represent the Wife? Does it seem like the Wife’s fears (male aggression, male rejection, etc.) are perhaps valid? After all, the knight that rapes the maiden at the beginning clearly does need to be reformed in some way; even King Arthur sees the necessity of punishing the knight for his action. The Old Hag gets the mastery only to surrender it again to her husband. Perhaps her thesis is more about curbing aggressive male dominance than it is about advocating female supremacy? What do you think?

I think this lesson plan is not only important for investigating Chaucer and his most canonical pilgrim, but also important given the events of the past month at UC Santa Barbara. Whether or not this prologue and tale are proto-feminist or anti-feminist, we can turn our pedagogy of the text into a method for teaching young students about feminism and about gender. There is obviously still an urgent need for such instruction.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed