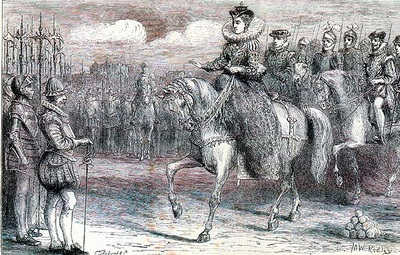

- Queen Elizabeth’s Armada Speech to the Troops at Tilbury, August 9, 1588, anthologized in Collected Works, pp. 325-6.

- Excerpt from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (5.5.1-26): Artegall, a powerful male knight, fights Radigund, an equally powerful female Amazon. He suffers both defeat and humiliation.

The Tilbury Speech

I have been persuaded by some that are careful of my safety, to take heed how I commit myself to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I tell you that I would not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear. I have so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects. Wherefore I am come among you at this time but for my recreation and pleasure, being resolved in the midst and heat of the battle to live and die amongst you all, to lay down for my God and for my kingdom and my people mine honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too!

Sink Rome, and their tongues rot

That speak against us! A charge we bear i' the war,

And, as the president of my kingdom, will

Appear there for a man. Speak not against it:

I will not stay behind.

Compare and contrast Elizabeth’s speech at Tilbury with Cleopatra’s decision that she will fight at war in man’s apparel. Why is Cleopatra’s biological sex a distraction for Antony (and the other men fighting), but Elizabeth’s presence is a rallying battle cry?

Note--this question prompted a lot of discussion from the students. It was a great way to get them to close read both the speech and the play, and it prompted some really interesting speculation about the types of feminine authority that were comforting or threatening.

The idea that Cleopatra would dress like a man when she went to war is interesting in light of both Act 3's representation of how monarchs use clothing to construct power and the trope of the Maid Martial in English poetry.

Clothing and Monarchical Power

Caesar. Contemning Rome, he [Antony] has done all this, and more,

In Alexandria: here's the manner of 't:

I' the market-place, on a tribunal silver'd,

Cleopatra and himself in chairs of gold

Were publicly enthroned: at the feet sat

Caesarion, whom they call my father's son,

And all the unlawful issue that their lust

Since then hath made between them. Unto her

He gave the stablishment of Egypt; made her

Of lower Syria, Cyprus, Lydia,

Absolute queen.

Mecaenas. This in the public eye?

Caesar. I' the common show-place, where they exercise.

His sons he there proclaim'd the kings of kings:

Great Media, Parthia, and Armenia.

He gave to Alexander; to Ptolemy he assign'd

Syria, Cilicia, and Phoenicia: she

In the habiliments of the goddess Isis

That day appear'd; and oft before gave audience,

As 'tis reported, so.

- Why is Caesar scandalized by the gold thrones and the costume of Isis? Is he scandalized by Antony “going native” or is he scandalized by Cleopatra’s queenship?

- Compare and contrast with both Fulvia and Octavia. How are "good" women supposed to act in this play, especially women that have some degree of power?

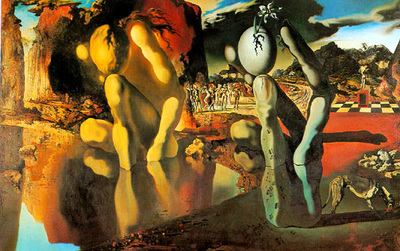

- Compare and contrast the costume of Isis (as we can glean from the images above) and the gown that Elizabeth wore in her Armada Portrait. How do these two sets of clothing perform female authority?

- Does Cleopatra perform her queenship or is it innate as Elizabeth claims that hers is (she “needs” no clothes—she is a queen even when she is in her petticoats)?

- What do you make of Elizabeth’s claim that she only needs her petticoats when she actually wore such elaborate clothing?

About the Armada Portrait, Billing writes:

Elizabeth constructs the enormous size of her political power in a number of ways, one of the most visual involving clothing. The costumes she wears in her portraits become ever larger throughout her reign, with hoop skirts, neck ruffs, puffed sleeves, and headwear growing increasingly more enormous while the costumes continue to accentuate her narrow waist and tiny hands... [Her] representational body stands for an eroticized political identity made all the more desirable because it hides the gendered, human body of the monarch, dwarfed beneath the royal robes.

While Elizabeth most likely stands before Parliament in her full robes of state [to deliver her speech], she figures herself in her undergarments, enticingly vulnerable yet unabashed and in control. She styles herself as clothed only in a garment worn close to the body and that, though it helped fashion the largeness of her outer layers, was not itself voluminous, enacting a kind of sartorial miniaturization that nonetheless asserts the queen’s authority: she can rule with her natural body, small and gendered female by the petticoats, and does not need her enormous robes of state.

Amazons

In the passage that we read, the Amazon (Radigund, a female) bests the knight (Artegall, a male) when the two are fighting. Then, she humiliates him by making him wear women's clothes and perform menial women's tasks related to cloth-making and sewing. The episode is based on the myth of Hercules and Omphale, which we discuss at greater length in conjunction with Act 4. Here are some stanzas 20-21 from Spenser's poem, which are an excellent starting point:

Then tooke the Amazon this noble knight,

Left to her will by his owne wilfull blame,

And caused him to be disarmed quight,

Of all the ornaments of knightly name,

With which whylome he gotten had great fame:

In stead whereof she made him to be dight

In womans weedes, that is to manhood shame,

And put before his lap a napron white,

In stead of Curiets and bases fit for fight.

So being clad, she brought him from the field,

In which he had bene trayned many a day,

Into a long large chamber, which was sield

With moniments of many knights decay,

By her subdewed in victorious fray:

Amongst the which she causd his warlike armes

Be hang'd on high, that mote his shame bewray;

And broke his sword, for feare of further harmes,

With which he wont to stirre vp battailous alarmes.

Cleopatra. O my lord, my lord,

Forgive my fearful sails! I little thought

You would have follow'd.

Antony. Egypt, thou knew'st too well

My heart was to thy rudder tied by the strings,

And thou shouldst tow me after: o'er my spirit

Thy full supremacy thou knew'st, and that

Thy beck might from the bidding of the gods

Command me.

Cleopatra. O, my pardon!

Antony. Now I must

To the young man send humble treaties, dodge

And palter in the shifts of lowness; who

With half the bulk o' the world play'd as I pleased,

Making and marring fortunes. You did know

How much you were my conqueror; and that

My sword, made weak by my affection, would

Obey it on all cause.

- Explain the imagery of the weakened or broken swords in both these passages from Spenser and Shakespeare.

- Cleopatra and Antony are allies not competitors, so how has she broken his sword?

- Why does Antony call her his conqueror? How does Radigund conquer Artegall? Is that the same thing?

- What kind of comment does this make about romantic love and/or attraction?

- What kind of comment does this make about masculinity and/or femininity?

- Spenser ostensibly wrote this poem for Queen Elizabeth. How does he get around offending her when he depicts female authority as emasculating for men, especially in Stanza 25?

- Does Shakespeare's text seem critical of female authority or nostalgic for it (he was writing this play after her death)?

- Who is to blame for Artegall and/or Antony’s defeat? The Spenserian narrator balances stanza 25 with the comment about Artegall’s “owne wilfull blame” (V. v. 20.2). Compare this to Enobarbus’ comment that it is “Antony only, that would make his will / Lord of his reason” who is at fault (3.3.3-4).

The kids easily linked the broken sword imagery with all of the other imagery of emasculation in the play. This, once more, raised the question of why it was energizing when Elizabeth supposedly appeared in armor to the troops at Tilbury, especially if it was enervating when Cleopatra and/or Radigund participated in battle with or against men.

I feel like we did not really do justice to Spenser's poem by breezing through it so fast. These questions, however, really engaged the students, and they prompted some excellent class discussion about what Early Modern English people might have thought of as appropriate female power. I think that one could overcome the rushed feeling that I experienced by not trying to cram it all in an hour's class. I would definitely recommend this collection of texts again, but I would advise you to spend more than an hour on it!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed