I pair a discussion of Act 1 of Shakespeare's play with an excerpt from an early modern pamphlet that was published in outrage at the queenship of Mary Tudor (the Catholic half-sister of Queen Elizabeth I, who was later nick-named "Bloody Mary").

The excerpt is from John Knox’s The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, and it can be found in the Norton Critical Edition of Antony and Cleopatra, p. 162.

Whatsoever repugneth to the will of god expressed in his most sacred word, repugneth to justice: but that women have authoritie over men repugneth to the will of God expressed in his word: and therefore mine author commandeth me to conclude without fear, that all such authoritie repugneth to justice…And if any man doubt hereof, let him mark well the words of the apostle, saying: I permit not a woman to teach, nether yet to usurp authority above man… say, we will suffer women to bear authority, who then can depose them? yet shall this one word of the eternal God spoken by the mouth of a weak man, thrust them every one in to hell. Jesabel may for a time sleep quietly in the bed of her fornication and whoredom, she may teach and deceive for a season, but nether shall she preserve her self, nether yet her adulterous children from great affliction, and from the sword of God’s vengeance, which shall shortly apprehend such works of iniquity.

In particular, Knox tries to naturalize male authority over women by appealing to some famous biblical passages, and he suggests that this authority is biological because of the "need" to control reproduction and prevent adulterous children. He links female political sovereignty to female promiscuity. He also suggests that any man who tolerates female authority makes himself weak and, therefore, becomes a threat to all men within this particular patriarchal power structure. As Knox asks, if women do gain a foothold into power, "who can depose them?" It is, therefore, just as important to police men as it is to police women.

Knox's attempt to undermine the political authority of Mary Tudor is surprisingly similar to the Romans' attempts to undermine both Cleopatra and Antony in Shakespeare's play. It is worth it to ask your students to think about how the Roman characters--exemplified most powerfully in Caesar but not limited to him--continuously proclaim that by loving Cleopatra and tolerating her authority in Egypt, Antony has emasculated himself and introduced a threat to Rome. This becomes the justification for war against Antony in the play to some extent: that in betraying his masculinity, he has betrayed Rome itself. One of the key questions to ask your students as you read through the play is whether the play endorses this patriarchal mindset or critiques it. To my mind, this is the key question about the play.

The question emerges immediately in the play in terms of Antony as a man of excess. He loves food, sex, and Cleopatra too much, according to the Romans. Philo opens the play with this discourse, arguing that Antony overflows the bounds of measure:

Nay, but this dotage of our general's

O'erflows the measure: those his goodly eyes,

That o'er the files and musters of the war

Have glow'd like plated Mars, now bend, now turn,

The office and devotion of their view

Upon a tawny front: his captain's heart,

Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper,

And is become the bellows and the fan

To cool a gipsy's lust.

Look, where they come:

Take but good note, and you shall see in him.

The triple pillar of the world transform'd

Into a strumpet's fool: behold and see.

Here are some of the pertinent passages:

...'tis to be chid

As we rate boys, who, being mature in knowledge,

Pawn their experience to their present pleasure,

And so rebel to judgment...

...thou [Antony] didst drink

The stale of horses, and the gilded puddle

Which beasts would cough at: thy palate then did deign

The roughest berry on the rudest hedge;

Yea, like the stag, when snow the pasture sheets,

The barks of trees thou browsed'st; on the Alps

It is reported thou didst eat strange flesh,

Which some did die to look on: and all this--

It wounds thine honour that I speak it now--

Was borne so like a soldier, that thy cheek

So much as lank'd not.

...Forbear me.

There's a great spirit gone! Thus did I desire it:

What our contempt doth often hurl from us,

We wish it ours again; the present pleasure,

By revolution lowering, does become

The opposite of itself: she's good, being gone;

The hand could pluck her back that shoved her on.

I must from this enchanting queen break off.

O well-divided disposition! Note him,

Note him good Charmian, 'tis the man; but note him:

He was not sad, for he would shine on those

That make their looks by his; he was not merry,

Which seem'd to tell them his remembrance lay

In Egypt with his joy; but between both:

O heavenly mingle! Be'st thou sad or merry,

The violence of either thee becomes,

So does it no man else.

Cleopatra is a lot like Antony as the two have characterized his excess. She has her own "wrangling" nature.

Fie, wrangling queen!

Whom every thing becomes, to chide, to laugh,

To weep; whose every passion fully strives

To make itself, in thee, fair and admired

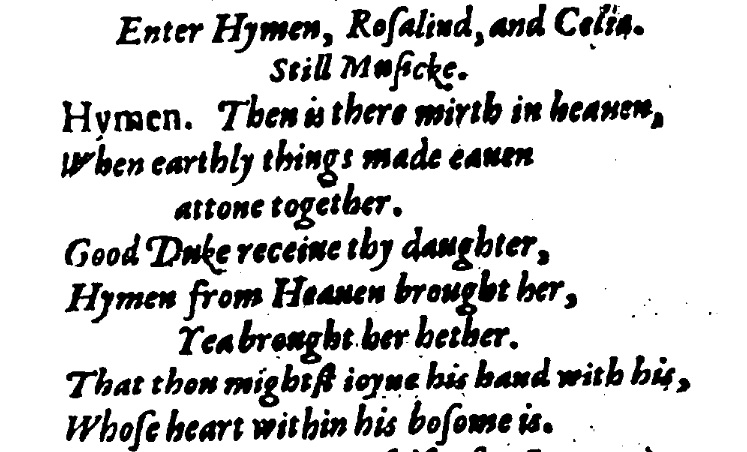

In this passage she sounds a lot like Rosalind, especially when she is disguised as Ganymede but playing "Rosalind" for Orlando:

I will weep for nothing, like Diana in the fountain, and I will do that when you are dispos'd to be merry; I will laugh like a hyen, and that when thou are inclin'd to sleep.

- Does Antony like Cleopatra’s “wrangling” nature? How do you know and why does it matter?

- Does she specifically wrangle with him because she knows he likes it, and she’s keeping him intrigued with her/keeping the passion alive?

- How does Antony and Cleopatra’s relationship make you think about Rosalind’s words in retrospect?

- Are Antony and Cleopatra comic characters trapped in a tragedy? Keep Meeker’s article in mind.

Here is my space.

Kingdoms are clay: our dungy earth alike

Feeds beast as man: the nobleness of life

Is to do thus [embraces Cleopatra] ; when such a mutual pair

And such a twain can do't, in which I bind,

On pain of punishment, the world to weet

We stand up peerless.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed