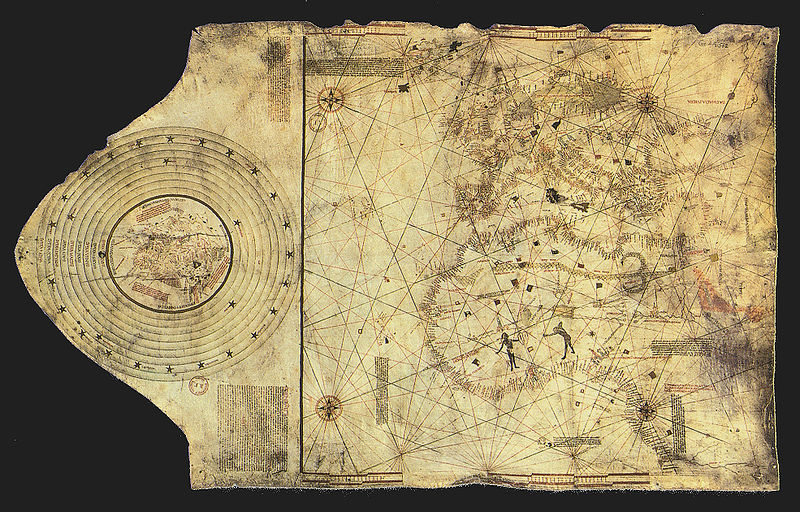

Columbus

It is useful to compare and contrast the two letters to each other: what kind of persona does Columbus create for himself in each letter? How does he consider the Native Americans? How does he consider the Spanish? In the first letter, why does he reference things like the nightingale and honeybees which were not in the New World but were in Spain? To whom is he writing in either letter and how does that affect the way we understand his tone?

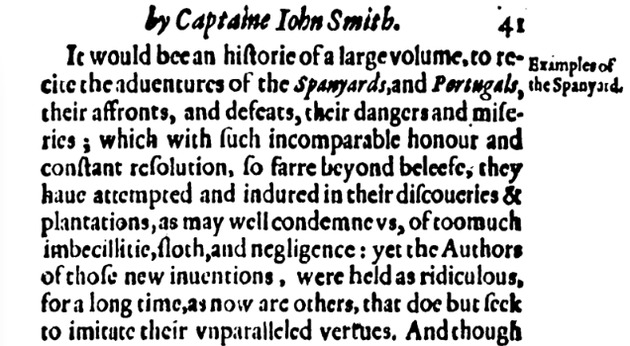

The Norton's selection opens up students to critique Columbus, but it also maintains enough ambiguity that they could still walk away from their reading with a rather simplistic and laudatory view of him still intact. I find it useful to bring in other voices to challenge their uncritical view. First, I give them a critique of the encomienda system that emerged from Columbus' policies, a critique that was written by Columbus' near contemporary Bartolomé de las Casa. A selection of de las Casas' The Very Brief Relation of the Devastation of the Indies (1552) is available in the Norton on pp. 38-42. In this section, de las Casas outlines in harrowing detail the atrocities that the Spanish were inflicting on the natives of the Caribbean. I like to ask my students: what is de las Casas’ seeming purpose in writing and how does that compare to Columbus? Compare and contrast the way that Columbus and de las Casas speak about the New World and its inhabitants. Also consider the way that these two early modern explorers use Hispaniola in order to draw contrasts between Native American culture and Spanish culture.

I also ask the younger students to read the essay by Ian W. Toll, “The Less Than Heroic Christopher Columbus,” in The New York Times, September 23, 2011, available online at this link, which is a really lovely review of Laurence Bergreen's Columbus: The Four Voyages, 1492-1504 (2012). Toll summarizes various "readings" of Columbus throughout history and praises Bergreen for his assessment of Columbus as one who "became progressively less rational and more extreme, until it seemed as if he lived more in his glorious illusions than in the grueling reality his voyages laid bare.” Bergreen's book would be good to excerpt for older students, but Toll's editorial in The New York Times is sufficient for my purposes with ninth graders. I ask them to explain Toll’s criticisms about Columbus and to consider if they accord with de las Casas’ text. Additionally, if the early modern explorers’ account of Hispaniola can tell us something about the way they view Spain, does Toll’s account of Columbus tell us something about how he views modern-day America? Why do you think we celebrate Columbus Day anyway?

Cabeza de Vaca

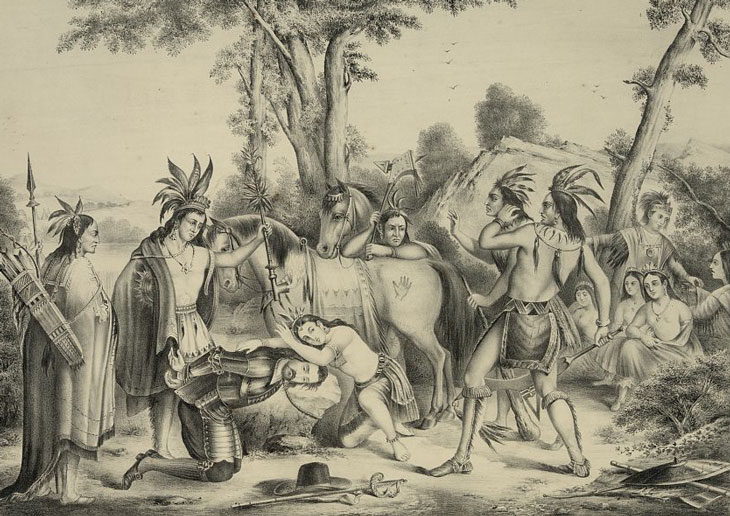

The Norton excerpt focuses on the initial period of enslavement and the reunion with the Spanish in Mexico city. I like to supplement the Norton's brief section with passages from The Relation that focus on what it was like for Cabeza de Vaca to become a faith-healer. As the excerpt above suggests, Cabeza de Vaca is on board with the colonialist project, but he also critiques the Spanish practice of enslaving the Indians, saying, "they received us with the same awe and respect the others had--even more, which amazed us. Clearly, to bring all these people to Christianity and subjection to Your Imperial Majesty, they must be won by kindness, the only certain way."

The way that he describes becoming a faith healer is especially useful for exploring his divided sense of self. He alternates between Machiavellian cunning as he seeks to augment the natives' misconception that he is from heaven and heartfelt wonder that God has seemingly chosen him as a vessel to bless, heal, and unite people who are sick or at war with each other. In short, he alternates between wanting to use the Indians and sincerely wanting to help them.

I ask my students to trace the "narrative" or agenda that is pro-colonization, pro-Spanish, and pro-exploitation. Then I also ask them to trace the "counter narrative" that is critical of colonization, the Spanish, and exploitation. We consider also what might account for tension between the two narratives: is this symptomatic of a divided loyalty, a divided sense of self, a product of being in a liminal space between "Spanish" and "Native American"? Is Cabeza de Vaca the "first" American?

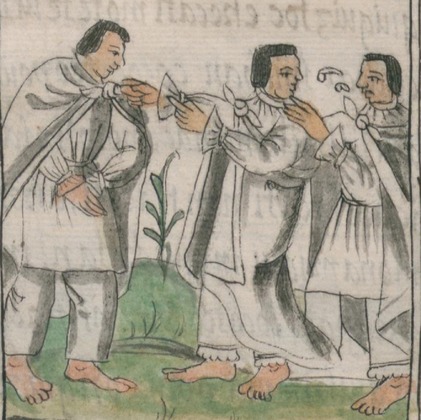

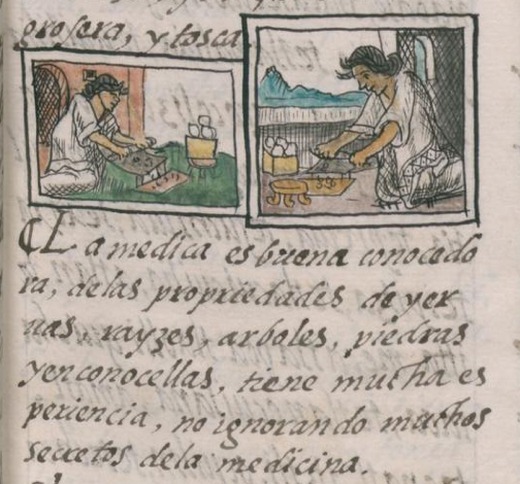

Sahagún

Very simply, Sahagún created a survey that he administered to the Aztecs about a wide range of topics. He administered the survey in their native language, Nahuatl, and he interviewed a wide range of people (including women). The survey was very simple in its basic premise. The written responses--given in Nahuatl and then translated into Spanish in a side-by-side translation--suggest that the majority of Sahagun's questions were three-part: 1) what is a ____? 2) what is a "good" ____?, and 3) what is a "bad" ____?

Sahagún intended the General History to be an all-purpose reference book: a dictionary, a cultural snapshot for missionaries who were coming in to convert the natives, and a record of a culture to preserve it. He also worked with the Aztec very closely. The research assistants for his study were all Aztec, and he employed Aztec "feather painters" to illustrate his book. Here are some of their beautiful illustrations:

World Digital Library offers high resolution scans of all volumes at The Florentine Codex, named for the best preserved copy of Sahagún's book (located at a library in Florence).

I find it very useful to compare and contrast Cabeza de Vaca and Sahagún, especially around the concept of empathy. I use the following as a paper prompt: Compare and contrast the representation of the Native Americans that we see in Cabeza de Vaca and in Sahagún. How does the form of these two texts (the method the writers use to present information) affect the content of their writing (the actual description of the New World and its inhabitants)?

The two forms are so different: one is a series of definitions and the other is a series of event set into narrative form like an adventure story. The former highlights Sahagún's willing decision to empathize with the Aztecs (even in their own language and giving preference to their own words) whereas the other shows Cabeza de Vaca as he is forced to undergo a partial (but still incomplete) process of acculturation to the native cultures of the American Southwest.

Historical relativists would urge us to keep these offenses in perspective. It was another era, they remind us, when men were governed by different moral and ethical codes.

--Ian Toll

RSS Feed

RSS Feed