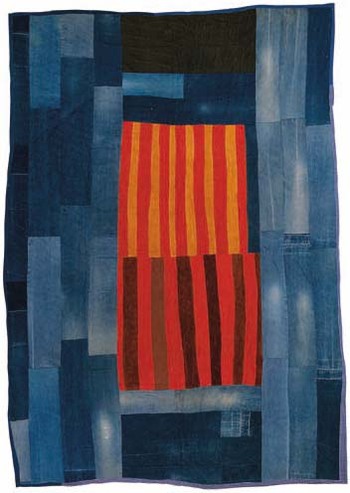

Quilting blogs cite Walker's story in praise (which is appropriate since these online communities connect the people who want to preserve this skill rather than the commodity it produces); moreover, quilts are increasingly put in museums as historical object and discussed in artistic communities as aesthetic objects.

For example, this breath-taking quilt (a variation on the "Lone Star" pattern that Walker mentions specifically in her short story) is housed at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, our nation's premier history museum (click on the image to see the even higher quality images in the museum's online catalog).

In contemporary writing, the quilt stands for a vanished past experience to which we have a troubled and ambivalent relationship.

--Elaine Showalter, "Piecing and Writing," 228

In the following blog post, I will both present my past strategies for teaching "Everyday Use" and also offer some new suggestions, incorporating research of various kinds.

Close Reading Questions:

- Is Mama always a reliable narrator? How does she go back and forth from seeing herself through her own eyes and seeing herself through Dee’s eyes?

- Compare and contrast Maggie and Dee, and then consider how Mama positions herself between her two daughters over the course of the story.

Mama's Perception of Maggie:

- Mama says, “Maggie will be nervous until after her sister goes: she will stand hopelessly in corners homely and ashamed of the burn scars down her arms and legs, eyeing her sister with a mixture of envy and awe." Is this what Maggie actually does?

- Mama says, “I hear Maggie suck in her breath. ‘Uhnnnh,’ is what it sounds like. Like when you see the wriggling end of a snake just in front of your foot on the road. ‘Uhnnnh.'" How does Mama seem to interpret Maggie’s grunt? What are other ways to interpret this sound?

- Why does Mama want to see Maggie as afraid of Dee?

Tense shifts:

“No, Mama," she says. “Not 'Dee,’ Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!”

“What happened to 'Dee’?” I wanted to know.

"She's dead," Wangero said. "I couldn't bear it any longer being named after the people who oppress me.”

- Notice the verbs in this passage. What happens? What impact does that shift have? What does Walker (or Mama) gain by that shift? Does, perhaps, present-tense narration seem to be a more passive indication of the narrator's immediate observations, whereas past-tense narration offers more of a sense that the narrator is actively shaping the events that she wants to tell into a story? Does it create a distance between Mama and Dee/Wangero?

Speech in "Everyday Use":

“She used to read to us without pity; forcing words, lies, other folks' habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn't necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious way she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand.”

"Impressed with her they worshiped the well-turned phrase, the cute shape, the scalding humor that erupted like bubbles in lye. She read to them.”

“I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero's hands and dumped them into Maggie's lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open.”

“And then the two of us sat there just enjoying, until it was time to go in the house and go to bed.”

New Directions:

Literary and historical research:

For older students: David Cowart's essay "Heritage and Deracination in Walker's "Everyday Use" (first published in Studies in Short Fiction 33 [1996]: 171-84, and then reprinted in Critical Essays on Alice Walker, ed. Ikena Dieke [Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999], 23-32) would be an excellent essay for the presentation assignment.

For younger students: Cowart's basic thesis--that Walker is critiquing certain elements of the rhetoric of 1960s black consciousness (specifically how superficial people are co-opting the radical aims of the movement to fashion a flashy but phony to "African" identity, which in turn undermines the movement's real and worthwhile goal to empower African-Americans)--is a thesis that can be explained by putting certain images or allusions of the short story into context. David White's essay "'Everyday Use': Defining African-American Heritage" makes a very similar argument in much simpler language for younger or less advanced students.

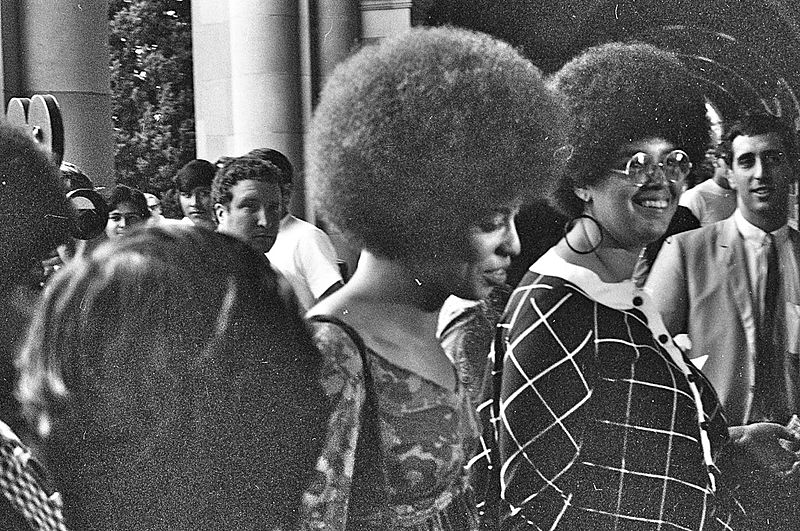

Either of the essays above could be a springboard into research into the civil rights movement, specifically, the Long, Hot Summer of 1967, the rise of an Islamic alternative to Christianity for African-Americans, Black nationalism and Afrocentrism, and even W.E.B. Dubois' defection to Africa in 1961. Dee fancies herself to be Angela Davis, but she alienates her family and isolates herself from the "heritage" that she claims to know and love so much.

In either case, students would read the literary essay and then research some of the historical figures and events mentioned in relationship to the civil rights movement. How does Walker present Dee/Wangero as superficial version of black consciousness and to what effect? How does that help to explain Mama's choice?

Imagining an alternate ending:

When the beautiful quilts made by the women of Gee's Bend, Alabama arrived at the Whitney Museum in New York, they were greeted with ecstatic praise by the art community. Michael Kimmelman of the New York Times wrote:

[The quilts] turn out to be some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced. Imagine Matisse and Klee (if you think I'm wildly exaggerating, see the show) arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South in the form of women, descendants of slaves when Gee's Bend was a plantation.

The fact that there is a price tag attached to the quilts drives home the idea that's implicit in Walker's short story: hanging the quilts on the hall instead of using them turns the quilts into a commodity instead of preserving the practice of making them.

One of the conversations, however, that emerges from this discussion is that younger generations (in Gee's Bend in particular) are newly motivated to learn the practice, and that the exposure that the women are getting now might contribute to a revival of the quilt-making tradition.

Another benefit of turning the quilts into aesthetic objects is to turn people's attention to these women as artists who matter. For example, the State of Alabama commissioned a series of interviews with the quilters to promote the "Year of Alabama Arts." I posted only one of the interviews below, but you can watch the whole playlist here.

An alternate research assignment would be to have students learn about the Gee's Bend quilters through the various links I've provided above and through their own independent research. Then ask students to write about how their research has affected their reading of Walker's short story either through expository writing or through a creative assignment such as revising the ending to the story or telling the story through Wangero's point of view. For ideas about incorporating creative writing into the classroom, see Erin Breaux's post Creative Writing in the Literature Classroom.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed