There were three main topics that we addressed in our discussion of Act 5: 1) Rosalind as a fluid signifier of both gender and desire, 2) the textual history of the marriage scene, and 3) the fabulous Epilogue and how it brazenly points to the male body of the boy actor underneath the feminine clothes of Rosalind. We compared this Epilogue to 8 accounts of boy actors from writers who were contemporary to Shakespeare.

Rosalind as a fluid signifier

Rosalind: I could find in my heart to disgrace my man's apparel, and to cry like a woman; but I must comfort the weaker vessel, as doublet and hose ought to show itself courageous to petticoat; therefore, courage, good Aliena. (2.4.3-6)

Rosalind (before finding out that the author of the poems is Orlando): Good my complexion! dost thou think, though I am caparison'd like a man, I have a doublet and hose in my disposition? (3.2.175-177)

Rosalind (after finding out Orlando has authored the poems): Alas the day! what shall I do with my doublet and hose? What did he when thou saw'st him? What said he? How look'd he? Wherein went he? What makes he here? Did he ask for me? Where remains he? How parted he with thee? And when shalt thou see him again? Answer me in one word. (3.2.197-201)

This comes back in terms of sexuality or desire as well. Through her code switching, Rosalind gets to occupy the full gamut of positions when it comes to being the gendered object of a person's desire:

Female object of a man's desire: Rosalind enjoys being the female/feminine object of Orlando’s desire in her role as “Rosalind” when she is educating Orlando, and she also enjoys being the object of his affection in real life.

Female object of a woman's desire: Arguably, Roz and Celia enjoy an intimacy that goes beyond friendship. Their closeness is remarked upon by everyone who discusses them, and Celia at times seems jealous of Rosalind's love for Orlando. The other characters (and even Celia) remark that her love of Rosalind exceeds Rosalind's love for her: "I see thou lov'st me not with the full weight that I / love thee" (1.2.6-7).

Male object of a man's desire: Rosalind deliberately chooses the name Ganymede because she also wants to be the male/masculine object of Orlando’s desire. She is thus an object of desire for Orlando in both the genders/sexes she performs.

Male object of a woman's desire: She seems to enjoy being the male object of Phoebe’s desire as well. Rosalind is very aware that Phoebe is falling in love with her. Let’s look at 3.5.43-44 and then also at 66-69. She knowingly toys with Phoebe to make her fall in love with Ganymede.

Why, what means this? Why do you look on me?

I see no more in you than in the ordinary

Of nature's sale-work. 'Od's my little life,

I think she means to tangle my eyes too!

[Aside] He's fall'n in love with your foulness, and she'll fall in love with my anger. If it be so, as fast as she answers thee with frowning looks, I'll sauce her with bitter words. Why look you so upon me?

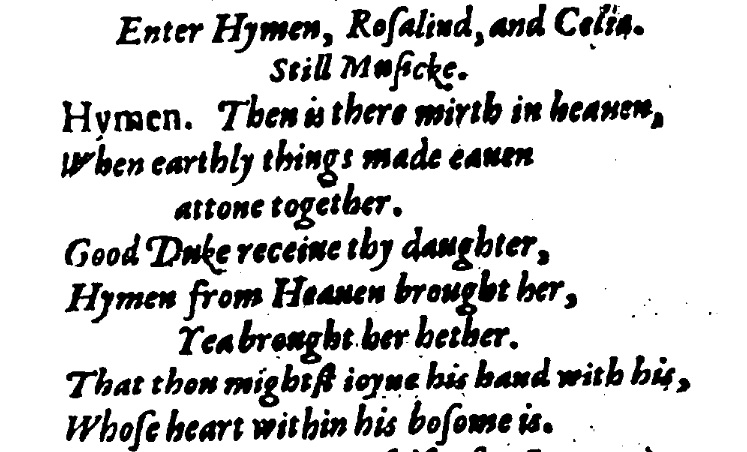

The Textual History of the Marriage Scene

Good Duke receive thy daughter,

Hymen from heaven brought her

Yea brought her hether [i.e., hither],

That thou might joyne his hand with his,

Whose heart within his bosome is.

We opened the classroom up to debate, simply using the following questions: Which pronoun should editors use and why? How does the pronoun matter in this scene and in the play? How does it change our view of the play if we use one pronoun or the other? This debate ended up being a MAJOR success in the classroom. It got them to see the stakes of editing practices on reception history, and it tied the marriage scene to the ambiguity of Rosalind's sexual fluidity that we had been discussing throughout the play. I highly recommend such a debate if you have students who are mature enough to handle it.

The Epilogue

This is a great opportunity to bring in accounts of boy actors that are roughly contemporary with Shakespeare. You can find all of these passages in the selection “Eight Accounts of Boy Actors” in the Texts and Contexts Edition of Twelfth Night ed. Bruce Smith pp. 276-278. Generally speaking, these accounts tend to fall into three camps:

1) People who argue (as we have seen) that boy actors are too sexy and will provoke audiences to "unclean" lust:

Philip Stubbes: Then these goodly pageants being done, every mate sorts to his mate, every one brings another homeward of their way very friendly, and in their secret conclaves (covertly) they play the sodomites, or worse.

John Rainolds: [Note] what sparkles of lust to that vice the putting of women’s attire on men may kindle in unclean affections.

Thomas Platter: “When the play was over, they danced very marvelously and gracefully together as is their wont, two dressed as men and two as women.”

Thomas Heywood: “Who cannot distinguish them by their names, assuredly knowing they are but to represent such a lady, at such a time appointed?”

Thomas Corayte: “I saw women act, a thing that I never saw before, though I have heard that is hath been sometimes used in London, and they performed it with as good a grace, action, gesture, and whatsoever convenient for a player, as ever I saw any masculine actor.”

George Sandys: “There [in Italy] have they their playhouses, where the parts of women are acted by women, and too naturally passionated.”

Part 1: he saw her with all passionate ardency seek and sue for the stranger’s love; yet he unmoveable, was no further wrought than if he had seen a delicate play-boy act a loving woman’s part, and knowing him a boy, liked only his action.

Part 2: If you did, madam, but see her speak, you would say you never saw so direct a mad woman. Such gestures and such brutish demeanor, fittinger for a man in woman’s clothes acting a Sybilla than a woman.

Part 3: [She was] the greatest libertine the world had of female flesh, and above any that fictions can set forth of truths manifest… being for her overacting fashion, more like a play-boy dressed gaudily up to show a fond loving woman’s part, than a great lady, so busy, so full of talk, and in such a set formality, with so many framed looks, feigned smiles, and nods, with a deceitful downcast look, instead of purest modesty and bashfulness…

It is not the fashion to see the lady the epilogue; but it is no more unhandsome than to see the lord the prologue. If it be true that good wine needs no bush, 'tis true that a good play needs no epilogue. Yet to good wine they do use good bushes; and good plays prove the better by the help of good epilogues. What a case am I in then, that am neither a good epilogue, nor cannot insinuate with you in the behalf of a good play! I am not furnish'd like a beggar; therefore to beg will not become me. My way is to conjure you; and I'll begin with the women. I charge you, O women, for the love you bear to men, to like as much of

this play as please you; and I charge you, O men, for the love you bear to women- as I perceive by your simp'ring none of you hates them--that between you and the women the play may please. If I were a woman, I would kiss as many of you as had beards that pleas'd me, complexions that lik'd me, and breaths that I defied not; and, I am sure, as many as have good beards, or good faces, or sweet breaths, will, for my kind offer, when I make curtsy, bid me farewell.

- Who is speaking here? Shakespeare, the boy actor, or the character of Rosalind?

- What implicit claims does this epilogue make about boy actors?

- Is there a focus on desire (as we saw in Stubbes and Rainold)?

- Is this epilogue a way for the actor/character to wink at the audience, who is in on the joke or the convention of having a boy actor play a woman’s part (like Heywood)?

- Is this a shocking way to pull back the curtain and deconstruct the natural way that the boy actor has played Rosalind (like what Coryate would say)?

- Is this a means for talking about artificial ways that men construct femininity for women through the theater (Wroth)?

This was an excellent way to end our discussion of the play. The students really like Rosalind because of how agential she is, and this play opens up discussion about postmodern and poststructuralist gender theory in a way that Twelfth Night does not. Reading the two of them together is a lot of fun, and it helps to clarifying some of the concepts that we will get to later when we talk about gender identity as opposed to gender performance.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed