Before I even begin with close reading questions, I like to point my students to larger questions about repetitions and motifs in the play.

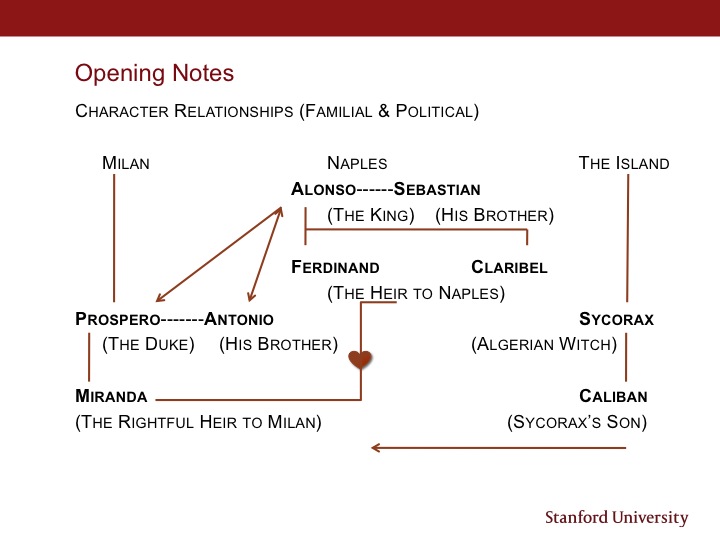

The first general set of themes that I ask them to think about are the sibling rivalries: 1) Prospero and Antonio, 2) Miranda and Caliban (if we think of Caliban as a type of surrogate brother) and 3) Alonso and Sebastian, a rivalry that becomes important in Act 2. I ask students to hold this in their minds, and think about possible sources for all of this pervasive sibling rivalry.

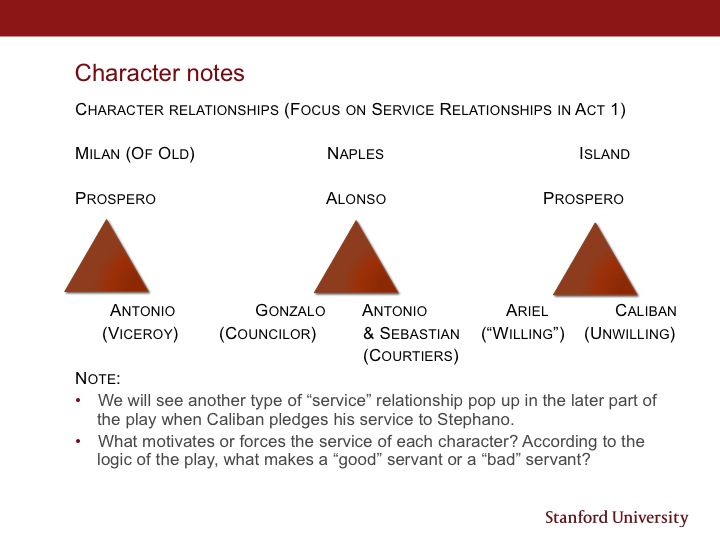

The second general set of themes that we discuss is the various types of master-servant relationships in the play, especially if we broaden our definitions of "service" to include courtiers and political subordinates:

Scene 1

- How do the characters come across in this scene? What are your initial impressions of the noble leaders (Alonso, Antonio, Sebastian, and Gonzalo) in comparison with the working sailors (esp. the Boatswain)?

- Shakespeare has other plays that contain a shipwreck, but that don’t show the shipwreck (ex. Twelfth Night). In those plays, the characters come on stage all wet and bedraggled and simply say, “Man, I was lucky to survive that terrible shipwreck!” Why does he show the shipwreck in The Tempest? What does that add?

The first question builds on the discussion of masters and servants in our "general themes" discussion. The students are quick to point out the kinds of hierarchies that are being either broken down or desperately upheld by the various characters. They get an immediate sense from Gonzalo's speech that social hierarchy really matters to these characters, even in the face of life-threatening catastrophe.

The second question can lead students in multiple directions. They often discuss the sense of chaos and fear that would be apparent from the scene, and good students also note that we the audience are like the characters on the stage in that we don't know yet that we are being manipulated by Prospero's magic. When we find out in 1.2 that none of the titular tempest was really as dangerous as it seemed, and that Prospero and Ariel were behind everything, we realized that we have been duped just as much as the Boatswain the the nobles. Prospero's seeming control extends beyond the stage even as far as our emotional experience.

In forthcoming scholarship, Bruce Smith argues that this scene helps to set up recurring contrasts in the play between music and noise that will enable Shakespeare to anticipate what we are now calling "sound art." Rather than listening for the sources of sound or the semantic meanings of sound, we are forced into a position of "reduced listening" where we hear the sound for what it is: raucous, terrifying noise. Whether or not we will be able to produce meaning or music out of the noise of The Tempest will depend on our position as listening subjects, rather than Prospero's position as magician (or even Shakespeare's position as playwright). Professor Smith has been kind enough to share his forthcoming essay with me, so I assign it as one of the student's presentation assignment articles.

Scene 2

The hour's now come;

The very minute bids thee ope thine ear;

Obey and be attentive. Canst thou remember

A time before we came unto this cell?

I do not think thou canst, for then thou wast not

Out three years old. 1.2.36-41

Miranda. Alack, what trouble

Was I then to you!

Prospero. O, a cherubim

Thou wast that did preserve me. Thou didst smile.

Infused with a fortitude from heaven,

When I have deck'd the sea with drops full salt,

Under my burthen groan'd; which raised in me

An undergoing stomach, to bear up

Against what should ensue. (1.2.151-158 )

...

Here cease more questions:

Thou art inclined to sleep; 'tis a good dulness,

And give it way: I know thou canst not choose. (1.2.184-186)

The question of Miranda's sexuality is, of course, fully addressed in this scene between the recounting of Caliban's attempted rape of her and her introduction to Ferdinand. I ask students to think about how messed up it is that Prospero makes Miranda go talk to Caliban moments before she meets Ferdinand... I ask them to put themselves in Miranda's shoes when her father makes her go talk with her unrepentant attempted rapist. Like he did before with Ariel, Prospero forces Miranda to relive a former trauma. We saw the payoff for Prospero when he uses a traumatic past with Ariel: what is the payoff for Prospero now, with Miranda? This leads to our last passage about Miranda and Prospero:

Prospero. The fringed curtains of thine eye advance

And say what thou seest yond.

Miranda. What is't? a spirit?

Lord, how it looks about! Believe me, sir,

It carries a brave form. But 'tis a spirit.

Prospero. No, wench; it eats and sleeps and hath such senses

As we have, such. This gallant which thou seest

Was in the wreck; and, but he's something stain'd

With grief that's beauty's canker, thou mightst call him

A goodly person: he hath lost his fellows

And strays about to find 'em.

Miranda. I might call him

A thing divine, for nothing natural

I ever saw so noble.

Prospero. [Aside] It goes on, I see,

As my soul prompts it. (1.2.409-421)

Prospero's control over the lovers' inward experience of love continues into the scene when he sets up artificial roadblocks between Miranda and Ferdinand: "They are both in either's powers; but this swift business / I must uneasy make, lest too light winning / Make the prize light." He is making Ferdinand and Miranda feel like they are the stars in their very own romantic comedy. He plays the stock character of the senex iratus, a paternal blocking figure such as Egeus in Midsummer Night's Dream. When Prospero starts playing that role, Ferdinand and Miranda fall in line as the lovers who prove the sincerity and depth of their love by overcoming and resisting his prohibition. He knows that putting up this false roadblock will only make them want each other more. They are puppets whom he manipulates, even in such a seemingly inward and intimate sphere such as their choice of whom they love and sexually desire.

The concept that we are "born" a certain way--that we have a core essence of who we are that cannot be changed no matter how much society pressures us to do so--is a humanist claim that we have a fundamental "human nature." Through Prospero, Shakespeare makes the opposite claim that our seeming essence--even something as fundamental to us as our choice in mate--can be and often is conditioned by society in ways that we are only dimly aware of. In this way, Shakespeare presents Prospero to us as a sort of post-humanist. He constructs Miranda's inward experience for her in a social experiment. Scientists use the word "controls" to describe the various elements that they can manipulate and eliminate in order to study causation instead of correlation; in the isolated environment of the island, Prospero can adjust most of the controls so that he can run his social experiment with maximum efficiency to make Miranda love the exact man whom Prospero has chosen for her. He is living the early modern patriarch's dream.

Students are generally pretty attached to the idea that they are born a certain way, and that they have a core essence that has not been constructed by society. Asking them to think about the implications of the idea that Miranda has been "programmed" to love Ferdinand usually leads to some pretty interesting discussions about how our culture might attempt to "program" their own inward experience.

One of the few things on the island that Prospero can't control (or at least can't control well) is Caliban. I will discuss Caliban more fully in next week's post!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed