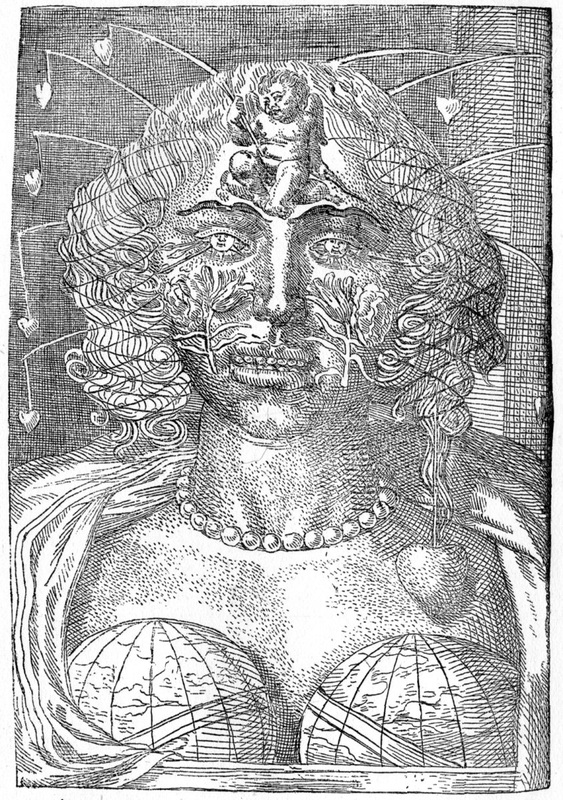

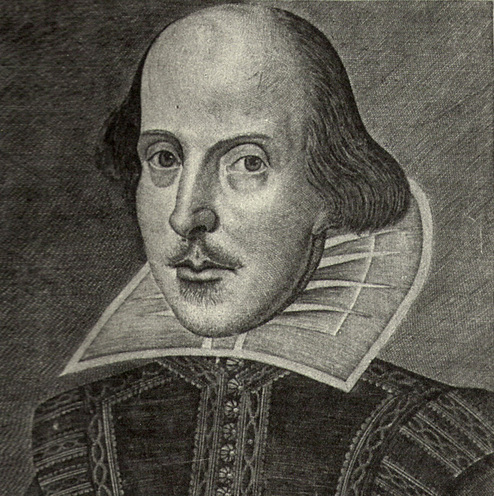

I've always wanted to teach a course on the entirety of Shakespeare's sonnet sequence (there are 154 sonnets in total). Perhaps some day I'll muster the courage to do it. Until that day comes, my plan is to continue using Sonnet 18 as an epitome of the Shakespearean sonnet. What follows is a discussion of how I use this poem in the college classroom to initiate conversations about poetics, prosody (i. e. how to read and analyze poetry), and the many useful themes, questions, and problems that characterize Shakespeare's sonnets.

I begin all of my undergraduate courses by having students look at Sonnet 18--the last of the sequence's opening "procreation poems," in which the speaker (the poet? Shakespeare? etc.) implores his (is it possible to imagine the speaker as "her"?) beloved to reproduce:

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st;

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

I ask individual students to identify the poem's defining words, images, metaphors, and so on. Then, finally, I ask them to think hard about the concepts of narration, characterization, and perspective. This trajectory towards literary critical abstraction allows us to discuss modes of address, conceits, and dramatic scenarios: the stuff of Shakespearean poetics (and theatricality), the elements he mobilizes, reconfigures, and subverts as the sequence unfolds.

This work keeps us busy. There's so much material in a single sonnet that sometimes it feels silly to try and talk about more than one in a day. By focusing on a handful of the sonnets in a limited number of class sessions, one sacrifices breadth for depth. (This painful decision mirrors my overall feeling of generalized anxiety when teaching Shakespeare: "What if they never know about the Dark Lady? How can I teach them anything about Shakespeare if they don't read King Lear? What of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece? etc.) You simply have to make choices, and hope that students come back for more later--either on their own or in another semester--which is likely to happen if you do justice to Shakespeare's genius and the beauty of his art.

The conceit of Sonnet 18 is a familiar one for many students: attractive people are LIKE beautiful weather; however, in the end, nothing compares to the beauty of the human form (and spirit). In the procreation sonnets, the poet writes consistently (but not always) in direct address to the object of his "affections"--a word that can be defined in different ways. The speaker's professed mission is to convince the poem's recipient to reproduce, mostly as a way of preserving beauty. Students of literature will immediately recognize Shakespeare's manipulation of the basic Petrarchan conceit, which holds that the speaker is a man writing to (about, in the wake of, etc.) his female beloved.

(I'm going to risk sounding grandiose for a moment. But, if you'll be patient, I can explain.) I think there's a lot in common between Shakespeare's sonnets (especially when taken as a sequence) and "the work" I'm doing on the coffee shop scene of Central New Jersey and environs (i.e. Brooklyn). The conceit of CNJSS is that there is a virtually omniscient narrator (who remains shadowy and unidentified, for the most part) who, like Hamlet (observer of all observers), is extremely attuned to his surroundings. I think of my "literary blog" as a medium through which I convey my own impressions of social life in a diverse urban environment. As my impressions change, and as I add new "scenes" to the unfolding sequence, I experiment with characterization, thematic clusters, vocabularies, and literary devices to elaborate the world I'm constantly in the process of reflecting/creating.

I think that this is precisely the kind of creative exercise that can help students understand Shakespeare and his cultural milieu. The Facebook Hamlet--which translates the entire saga into a single, albeit subtly complex page--is merely one of several social media "projects" that play well in the classroom. The risk in using such material is that we as teachers fear we're "dumbing Shakespeare down." But such criticisms fail to take into account the fact that Shakespeare was always a "popular" artist--that all of his writings were meant for consumption by the masses--even the sonnets, which first achieved book form and broad circulation in 1609. The medium matters, of course. But the goal for high school students and undergraduates should be to understand Shakespeare's own "media"--drama and poetic verse, as performance and printed literature--and not just the content of his work (i. e. his "message"). For, the two are inextricably linked. Shakespeare in other words may not be Shakespeare, but the act of cultural translation is, for nearly all students, an important step in getting at the original.

I hope to use more creative exercises when teaching lyric poetry in the future.When scribbling down notes for CNJCSS, I often find myself reflecting on the sonnets, both as objects of composition (i. e. things that were written) and reception (texts that were meant to be heard and/or read, artifacts in circulation). How does Sonnet 18, for instance, reflect and play self-consciously with the complicated relations between author, poetic object, and audience? Why might an interpretation of the poem depend upon who else is hearing/reading the words on Shakespeare's page? Why is it fair to think about Early Modern sonnet sequences as an ancestor of literary experiments that are taking place right now on social media platforms?

I hope I've given you some food for thought. Please write to me at [email protected] -- I'd love to hear from you. I have plenty of resources to share with you. Facebook users interested in CNJCSS can visit this page and then "Like" it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed