From my smart friends:

From Ari Friedlander, professor at University of Dayton. Dr. Friedlander studies early modern English literature and pop culture and the history and theory of gender and sexuality. He's also generous, hilarious, and a really good listener:

Never taught it, but always thought it might be fun to do with Northrop Frye's "Archetypes of Literature" essay. It's not technically about the poem, but it could work anyway.

I had them do some group work where they analyzed the changing descriptions of different aspects of the setting: the sea, the sun, the weather, the sea creatures, and the ship. I assigned each group one of these categories, and they had to find the relevant descriptions and explain how they change/shift throughout the poem and what that contributes to the plot.

We talk about the ballad, archaic language, the circulation of the Mariner's tale, genre, environmentalism, and we talk a lot about zombies. In terms of environmentalism, I introduce the Book of Genesis' notion of man's environmental stewardship over nature, and we discuss if this is the rationale behind the poem's message, as stated in the last few stanzas. It isn't as if the Mariner completes his voyage and then surrounds himself with nonhuman animals--he remains anthropocentric. So I ask them: what, then, is the function that animals are put to in the poem? And doesn't this reinforce a particular human/animal hierarchy? Also, I like to push back against the stewardship theory by exploring how ineffable and powerful nature is in the poem, and how impotent man seems to be against it.

I ended up using almost all of these suggestions, but in a modified form. I assigned the following articles, which drew on archetypal language in order to draw connections between the poem and the Book of Revelation. I had a student present each article according to the homework presentation assignment.

Chandler, Alice. “Structure and Symbol in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.’” Modern Language Quarterly 26.3 (1965): 401-413.

Gose, Eliot. “Coleridge and the Luminous Gloom: an Analysis of the Symbolical Language in ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.’” Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 75.3 (1960): 238-244.

I did break the students up into groups to focus their reading on certain recurring motifs or themes in the poem, and I noticed that all of these motifs came back to a discussion about the indeterminacy in the poem between 1) free will and fate and 2) salvation and damnation. This helped me to craft the following questions for my students.

Reading and discussion questions:

- What are these two major moments about animals in the poem?

- What is the Albatross like? How does the Mariner react to it? Why?

- What are the water snakes like? How does he react to them? Why?

- How does the Mariner make choices?

- How does he moves from one place to the other? Is the ship an effective means by which he can control his movements? Why or why not? If the sea were a “character” in the poem, how would you describe it? Is is more or less powerful than the ship?

- Is the Mariner active (agential) or passive (acted upon)?

- Does it matter that both of his two major interactions with animals happen because of impulse rather than because of purposeful decision making?

- What is the significance that the listener is going to a wedding?

- What is the significance of the Mariner’s hypnotic hold over the wedding guest? How does the Mariner’s relationship to free will relate to the Wedding Guest’s lack of free will?

This is the story of the fall and the redemption of the Mariner. The fall is seen in his Judas-like betrayal of a Christ-like figure, the Albatross; The redemption is seen in the eschatological language and the vision of the New Jerusalem as recounted in the Book of Revelation. The Mariner is like John the Apostle.

This is the story of a damned man. His depravity is made apparent through the shooting of the bird, and his redemption is far from certain. In fact, 1 Thessalonians 4:17 (the scriptural bases for the idea of the “Rapture”) would have us believe that the fact that he is left behind corroborates his damnation; the "dead in Christ" and "we who are alive and remain" will be "caught up in the clouds" to meet "the Lord in the air.

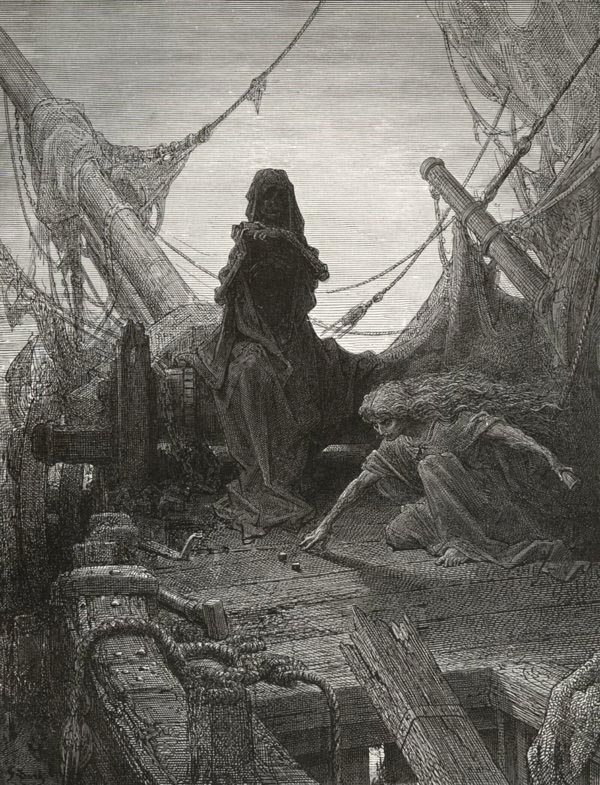

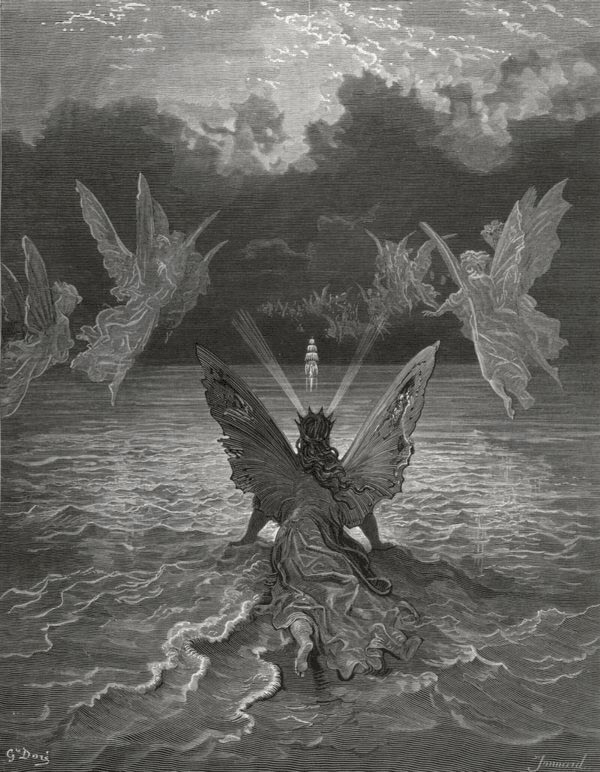

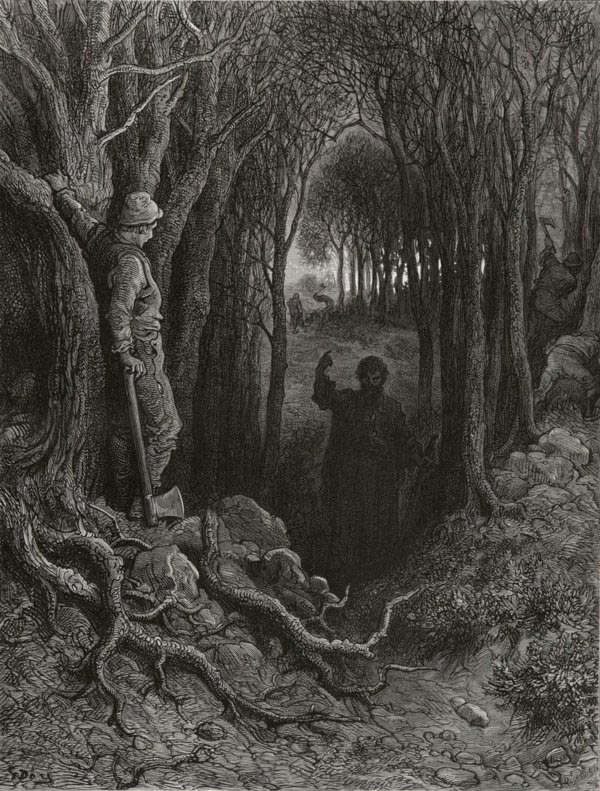

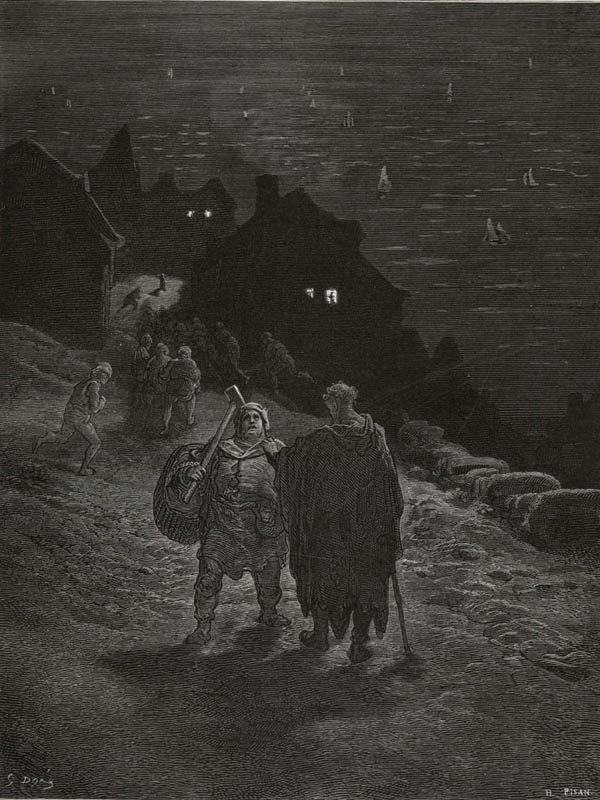

At this point, I pulled in a series of images from Gustave Doré's illustrations of the poem. In each, we looked at the specific lines that Doré is illustrating.

By the way, the Doré illustrations can all be found at this page, hosted by the library of the University of Buffalo.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed