Again, I do not think it is necessary for high school students to read the entirety of the pamphlet. I think that two passages in particular are especially pertinent and that they help to deepen the conversation about Viola's cross-dressing in the play. The first passage to consider is below. The character Hic Mulier is responding to the criticism that it is unnatural for women to dress like men:

To alter creation were to walk on my hands with my heels upward, to feed myself with my feet, or to forsake the sweet sound of sweet words for the hissing noise of the Serpent. But I walk with a face erect, with a body clothed, with a mind busied, and with a heart full of reasonable and devout cogitations, only offensive in attire, inasmuch as it is a stranger to the curiosity of the present times and an enemy to Custom? Are we then bound to be the flatterers of Time or the dependents on Custom? Oh miserable servitude, chained only to Baseness and Folly, for than custom, nothing is more absurd, nothing more foolish.

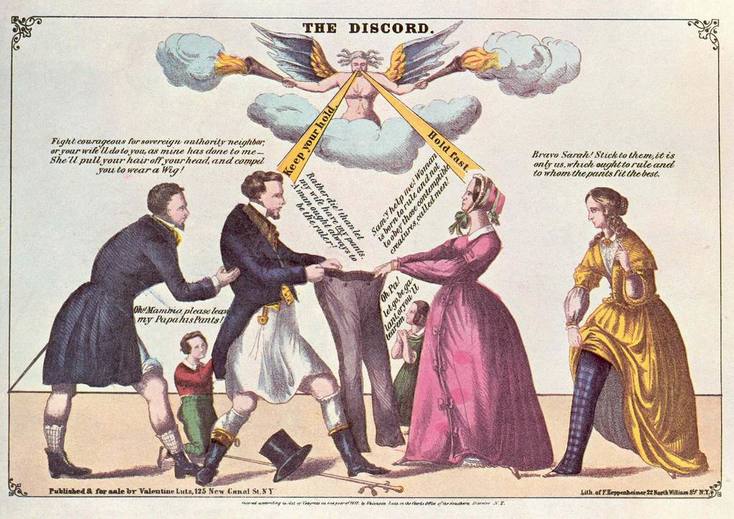

Students generally like this line of argument for several reasons. They are at an age where they are defining their own sense of self through their tastes (including their clothes), and this means that they are resisting the fashions that their parents had previously picked out for them. And while some more conservative students might be personally uncomfortable with men cross-dressing as women, almost everyone in Western culture is used to the idea of women wearing pants now. Moreover, students intuitively feel that the seventeenth-century derision at women's adopting masculine modes of dress was somehow means of social control to keep women in their subordinate places. Even without having studied about the ways that masculine modes of dress have been tied to movements of social progress for women, students seem to pick up on this instinctively because of popular iconography.

Generally speaking, students like Hic Mulier's argument about gendered fashion being tied to custom because it is surprisingly modern, and they can relate to it. While many students have deep misunderstandings about feminism, they generally do think that the social progress of women over the past century has been both important and good. Unlike the so-called "men's rights" websites, most students (of both genders) do not think that the social good of "the family" necessitates the repression of female agency and subjectivity. For instance, they generally think that it is a good thing that women can vote and work; however, the idea that men and women are genetically hard-wired a certain way by Nature (either by God or evolution) is one that permeates culture so deeply that they don't always question it.

This conversation is a good one to have in conjunction with Twelfth Night because the play does make certain claims about the how "natural" gender is in relation to biological sex. There are two really important scenes to consider.

The first is the fight that Sir Toby attempts to set up between Sir Andrew and Cesario. When Cesario/Viola is contemplating how disastrous a fight with Sir Andrew might be for her she says, "Pray God defend me! A little thing would / make me tell them how much I lack of a man." Although Shakespeare has taken great pains to show that Sir Andrew is just as unwilling to fight as Cesario, and even suggests that Cesario/Viola's unwillingness to fight has to do with never having been trained how to fight, Viola's language here suggests that it is her biological sex itself that will expose her. It's worth it to spend a little bit of time to ask students about 1) why the play suggests that Cesario might lose (or win) a fight with Sir Andrew, and, 2) why Viola assumes that Cesario would absolutely lose in a fight with Sir Andrew? Also, how do Sir Toby's pranks become a means for policing gender norms?

The second scene to consider is the final scene. The following passage, spoken by Sebastian to Olivia, is especially pertinent.

So comes it, lady, you have been mistook:

But nature to her bias drew in that.

You would have been contracted to a maid;

Nor are you therein, by my life, deceived,

You are betroth'd both to a maid and man.

Does this image suggest that there is something inherent and natural about gender and/or sexuality that causes men and women to act in fundamentally different ways so that they will inevitably end up in procreative pairs? If so, does that suggest that this play is a more conservative one than we might otherwise think (i.e., does it line up with the argument made by the men's rights groups cited above) ? Alternatively, does the play suggest that Viola's playful adoption of masculine attire is a sort of liberation from gendered norms, and that this freedom is ultimately a good thing because it brings around a happy ending for most of the characters?

This brings me to the second passage that I point my students to in Haec Vir:

Why do you rob us of our ruffs, of our earrings, carcanets, and mamillions, of our fans and feathers, our busks, and French bodies, nay, of our masks, hoods, shadows, and shapinas [?]… Now since according to your own Inference, even by the Laws of Nature, by the rules of Religion, and the Customs of all civil Nations, it is necessary there be a distinct and special difference between Man and Woman, both in their habit and behaviors, what could we poor weak women do less (being far too weak by force to fetch back those spoils you have unjustly taken from us), than to gather up those garments you have proudly cast away and therewith to clothe both our bodies and our minds?... Cast then from you our ornaments and put on your own armor; be men in shape, men in show, men in words, men in actions, men in counsel, men in example. Then will we love and serve you; then will we hear and obey you…

As I mentioned in my post about the opening lines of Twelfth Night, Orsino's call for more love and more music is an unusual way to begin the play in terms of plot. The plot really begins with Viola's miraculous survival after the ship crashes, but Shakespeare chooses to begin the play with Orsino's now-famous lines, "If music be the food of love, play on." David Halperin has argued that pre-modern cultures associated love with women and war with men, so much so that a man's expression of desire for women or sex could be understood as unmanly in itself. That is, the desire for women or for heterosexual love often registered as effeminizing or weakening. This logic still exists in the misogynistic websites like the one I referenced above, which not only offer advice for men who want to improve their "game" (creating an association between sex and conquest) but also deride men who actually dare to love women as being "whipped" or "betas."

It is worth it to ask your students to compare and contrast Orsino in the opening and closing scenes of the play. Does he seem different? How so? How has learned or grown? Orsino reveals that he “partly know[s]” that Olivia is in love with Cesario. How does that affect the way we think of Orsino? Also, Orsino plans to KILL Cesario to spite Olivia, and Viola seems to be ok with that! What is up with that? How does that affect the way we think of the relationship between Orsino and Cesario? Orsino wants Viola in her women’s weeds, but also talks sweetly to the page, naming her/him "Cesario," and calling attention to “his” male gender? (5.1.362-3). Why does he keep calling Viola "Cesario," even after he learns that she is really a woman in disguise as a boy? Has Orsino become more stereotypically masculine (ask them to define what they mean by "masculine"), and does the play register this as a good thing or a bad thing? Is the play making a similar argument to the one that the character Hic Mulier makes above at the end of Haec Vir, i.e., that Orsino has been too feminine and that once he becomes more masculine, he will be worthy of seeing Viola in her women's weeds? Is this argument similar to the misogynist websites today that tell men that the way to "score" women is to become more "alpha" and be more willing to degrade and objectify women? Is Shakespeare critiquing or participating in this rhetoric?

These are great questions with which to end a study of this play; they tie the play to both early modern and contemporary debates about gender, so students will be thinking about both the context in which Shakespeare was writing and how Shakespeare's play is directly connected to their own lives. After teaching this play in the context of clothing and gender, I think I will find it hard now to teach it without these two pamphlets from the querelle de femmes pamphlet war!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed