In teaching Acts 1-2 of the play, I like to pair Shakespeare with both Stubbes and Prynne. In Acts 3-4, we consider the following selections from Rainolds and Chamberlain:

- Section on the theater’s ability to provoke lust from John Rainolds’ The Overthrow of Stage Plays pp. 10-11 from EEBO

- John Chamberlain’s letters from 1620 on the fad for women to wear masculine clothing in the Norton Critical Edition of The Roaring Girl, pp. 120-121

[A]lthough our weak eyesight could discern no cause, why so small a matter [biblical injunctions against cross-dressing], as flesh and blood might count it, should be controlled so sharply. Howbeit, if we mark with judgment and wisdom, first, how this precept is referred by learned Divines to the commandment, “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” some expressly making it a point annexed thereto, some impliedly in that either they knit it to modesty, a part of temperance, or note the breach of it as joined with wantonness and impurity… [Note] what sparkles of lust to that vice the putting of women’s attire on men may kindle in unclean affections. (Rainolds, 10)

The following set of questions are meant to tie our discussion of As You Like It with our sections earlier discussions of Twelfth Night:

- In our discussion of Viola, we talked about the Cesario as being attractive because the character's female body was visible underneath her masculine disguise (especially when Orsino talks about Cesario's lips and voice being like a woman's). Are these Puritan authors suggesting that the same logic applies to boy actors dressed like women, or is the disguise itself what attracts?

- Do these authors imagine sexuality the way we imagine it today?

- Does it matter that it’s a boy actor’s body underneath Rosalind's clothes? Does putting the boy actor back in gender-appropriate clothing control the lust of the audience or ramp it up more?

I then ask students to consider the poems that Orlando puts on the trees.

- Why does Orlando put the verses on the trees?

- What do you think of the poems? Are they good? Why or why not?—Consider both content and form

- Compare and contrast Orlando and Silvius in the ways they conceptualize both the male experience of desire and women more generally.

- How do these poems provoke in Rosalind a desire to “school” Orlando?

- Is she expressing a similar frustration to what Phoebe says in the following passage:

Lie not, to say mine eyes are murderers.

Now show the wound mine eye hath made in thee.

Scratch thee but with a pin, and there remains

Some scar of it; lean upon a rush,

The cicatrice and capable impressure

Thy palm some moment keeps; but now mine eyes,

Which I have darted at thee, hurt thee not;

Nor, I am sure, there is not force in eyes

That can do hurt. (3.5.19-27)

Amen. A man may, if he were of a fearful heart, stagger in this attempt [i.e., marriage] ; for here we have no temple but the wood, no assembly but horn-beasts. But what though? Courage! As horns are odious, they are necessary. It is said: 'Many a man knows no end of his goods.' Right! Many a man has good horns and knows no end of them. Well, that is the dowry of his wife; 'tis none of his own getting. Horns? Even so. Poor men alone? No, no; the noblest deer hath them as huge as the rascal…As the ox hath his bow, sir, the horse his curb, and the falcon her bells, so man hath his desires; and as pigeons bill, so wedlock would be nibbling. (3.3-37-44, 61-3).

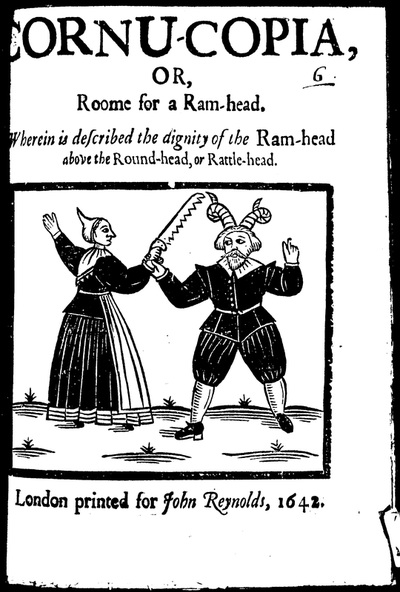

Touchstone's cynical argument about both men and women is echoed in the recurring imagery of cuckold horns in the play. According to myth, men who have wives that have cuckolded them (i.e., committed adultery on them) grow horns that are invisible to them but visible to other people. The horns are a sign of social stigma and shame, but one that a man is powerless to detect, much less defend himself against. The following images show some early modern woodcuts of men with cuckold horns.

Rosalind. There is none of my uncle's marks upon you; he taught me

how to know a man in love; in which cage of rushes I am sure you

are not prisoner.

Orlando. What were his marks?

Rosalind. A lean cheek, which you have not; a blue eye and sunken,

which you have not; an unquestionable spirit, which you have not;

a beard neglected, which you have not; but I pardon you for that,

for simply your having in beard is a younger brother's revenue.

Then your hose should be ungarter'd, your bonnet unbanded, your

sleeve unbutton'd, your shoe untied, and every thing about you

demonstrating a careless desolation. But you are no such man; you

are rather point-device in your accoutrements, as loving yourself

than seeming the lover of any other.

- Compare and contrast this description of the lover’s role to Jaques’ description: “And then the lover, / Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad / Made to his mistress' eyebrow.”

- What function does clothing play in Rosalind’s description of a lover? Is it a costume or a sign of a role that a man plays at a certain stage in his life? Does it mark Orlando's love-sickness as artificially constructed? Why or why not?

- What does it matter that Rosalind calls Orlando out for not playing a role well enough? Does it end up denaturalizing some of the stereotypes that Orlando tends to think in--about the male experience of being in love or about women more generally?

Orlando. Did you ever cure any so?

Rosalind. Yes, one; and in this manner. He was to imagine me his love, his mistress; and I set him every day to woo me; at which time would I, being but a moonish youth, grieve, be effeminate, changeable, longing and liking, proud, fantastical, apish, shallow, inconstant, full of tears, full of smiles; for every passion something and for no passion truly anything, as boys and women are for the most part cattle of this colour…

Orlando. I would not be cured, youth.

Rosalind. I would cure you, if you would but call me Rosalind, and

come every day to my cote and woo me.

Orlando. Now, by the faith of my love, I will. Tell me where it is.

What Freud is commenting on is a pathological version of something that might already be at play in As You Like It: women’s sexuality is constructed as two mutually exclusive modes—1) an idealized virginity that is worshipped and loved (Silvius and Orlando), and 2) a degraded sexuality that is both uncontrollable, shameful, and polluting (Touchstone).

It is worth noting that both of these poles of female sexuality are constructed by patriarchal thinking. Such stereotypes are a means of policing women’s actions; however, they can also affect how men see both women and themselves in relation to women.

Rosalind "cures" Orlando of loving in a stereotypical way by ramping up the misogynistic stereotypes about women to eleven--to a point that is so ridiculous that Orlando seemingly stops accepting patriarchal stereotypes about women. In the mock marriage scene in Act 4, he seems to relinquish his attempts to signify what Rosalind will be or do, and he instead just rolls with the punches that "Rosalind" (i.e., the character that Ganymede plays) dolls out to him:

Rosalind. Now tell me how long you would have her, after you have

possess'd her.

Orlando. For ever and a day.

Rosalind. Say 'a day' without the 'ever.' No, no, Orlando; men are

April when they woo, December when they wed: maids are May when

they are maids, but the sky changes when they are wives. I will

be more jealous of thee than a Barbary cock-pigeon over his hen,

more clamorous than a parrot against rain, more new-fangled than

an ape, more giddy in my desires than a monkey. I will weep for

nothing, like Diana in the fountain, and I will do that when you

are dispos'd to be merry; I will laugh like a hyen, and that when

thou are inclin'd to sleep.

Orlando. But will my Rosalind do so?

Rosalind. By my life, she will do as I do.

Orlando. O, but she is wise.

This is where the clothing comes back to the fore: Orlando has put Rosalind on a pedestal, especially in his poetry to her. She removes herself from the pedestal through her male clothes and becomes his friend first. He gets to know her as a person who has an interior life the same as his. Then she challenges him to think about how he has tried to construct her artificially in his mind through stereotypes, and she shows him how dangerous such thinking is for the relationship between men and women. The twinned strategies that she uses help her to deconstruct his simplistic thinking.

Yesterday the bishop of London called together all his clergy about this town, and told them he had express commandment from the King to will them to inveigh vehemently and bitterly in their sermons against the insolency of our women, and their wearing of broad-brimmed hats, pointed doublets, their hair cut short or shorn, and some of them stilettos or poniards, and other such trinkets of like moment, adding withal that if pulpit admonitions will not reform them he would proceed by another course. The truth is, the world is very far our of order, but whether this will mend it, God knows. (Chamberlain)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed