One of the first questions that I ask my students to think about is why does Rosalind choose the name Ganymede. They often do not know the allusion to the classical myth, so it is worth it to show the following passage from Ovid.

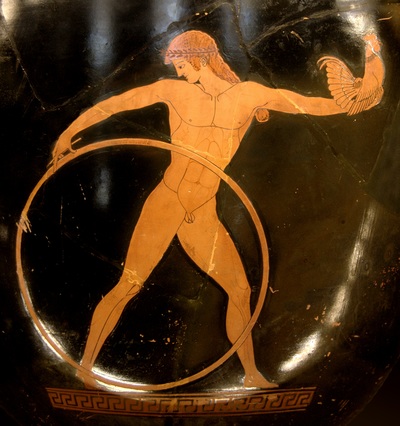

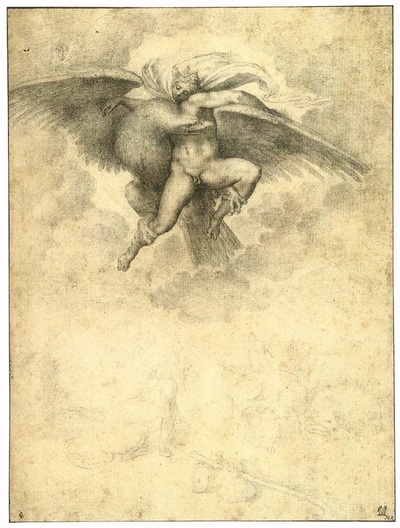

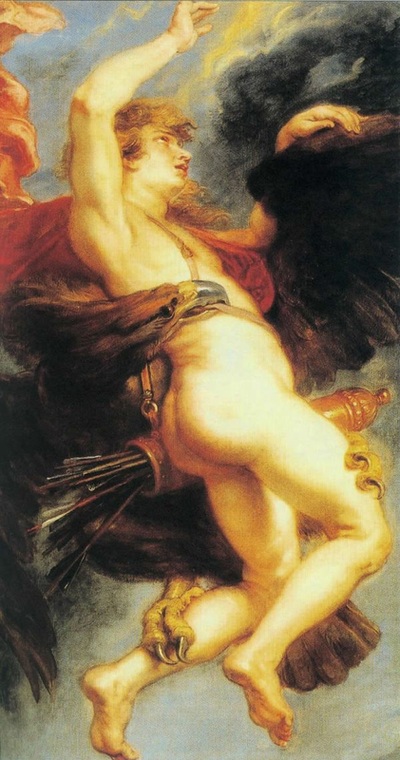

Ganymede in Classical and Renaissance Art

But, as James Saslow has argued, Ganymede was an enduring symbol for the beautiful young male who attracted homosexual desire: “The very word ganymede was used from medieval times well into the seventeenth century to mean an object of [male] homosexual desire.” The fact that students don't know this reference anymore might have more to do with how the myth and its iconography have changed since the eighteenth century. Michael Preston Worley has argued that homoerotic aspects of the legend were rarely dealt with after this time period and were, rather, "heterosexualized." Instead, the image of Ganymede was that of a naive adolescent accompanied by an eagle.

In order to show my students how well known and pervasive this myth was when Shakespeare was writing, I offer them a slide-show of art before, during, and shortly after Shakespeare was writing.

The king of the gods [Jupiter] once burned with love for Phrygian Ganymede, and to win him Jupiter chose to be something other than he was. Yet he did not deign to transform himself into any other bird, than that eagle, that could carry his lightning bolts. Straightaway, he beat the air with deceitful wings, and stole the Trojan boy, who still handles the mixing cups, and against Juno’s will pours out Jove’s nectar.

-- Ovid, Book X:143-219 of Metamorphoses

Rosalind: I'll have no worse a name than Jove's own page,

And therefore look you call me Ganymede.

But what will you be call'd?

- Why would Rosalind chose this name, out of all the possibilities that exist, in light of this tradition in art and literature? How would it change the play if she wants to be the male object of homosexual desire for Orlando?

- On a related note, why would Celia choose “Aliena”? How is her name revelatory of her character? Is she an alien, and (if so) what or whom is she alienated from?

This discussion is worth pairing with brief excerpts from the very long tradition of Puritan writing against the clothing and theater as hotbeds of sexual impropriety that become "schools of abuse." I ask my students to read the following passages in conjunction with Acts 1-2 of As You Like It:

- A section on the dangers of theatrical cross-dressing from William Prynne’s Histriomastix in the Norton Critical Edition of As You Like It, pp. 214-217

- A section “Doublets for Women in England” from Philip Stubbes’ The Anatomy of Abuses in the Norton Critical Edition of The Roaring Girl pp. 118-119

- A section “Stage Plays and Enterludes, with their Wickedness,” from Philip Stubbes’ The Anatomy of Abuses pp. 101-107 from Early English Books Online (EEBO) *You will need institutional access to this database to see the archive

The passages about cross-dressing (either on the stage or in "real life") and about the theater as a school of abuse are especially interesting because of how the Puritans handle the questions of identity and desire. On the one hand, we see a strong attempt to fix signs and signifiers in static relation to each other (both of the following excerpts are from Stubbes). Part of the wickedness of cross-dressing and stage plays is that they are self-evidently skewing that natural, even holy relationship between the sign and the signifier:

In the first of John we are taught that the word is God, and God is the word; therefore, whoever abuseth this word of our God on stages in plays and interludes abuseth the deity of God in the same. (102)

So that whether they be the one [religious plays of “divine matter”] or the other [secular plays of “profane matter”], they are quite contrary to the word of grace, and sucked out of the devil’s teats to nourish us in idolatry, heathenry, and sin. (103)

The shameless gestures of players serve nothing so much as to move the flesh to lust and uncleanness. (103)

Do they not induce to whoredom and uncleanness? Nay are they not rather plain devourers of maidenly virginity and chastity? For proof whereof, but mark the flocking and running to theaters and curtains…where such wanton gestures, such bawdy speeches, such laughing and fleering, such kissing and buffing, such clipping and cussing, such winking and glancing of wanton eyes and the like is used as is wonderful to behold. Then these goodly pageants being done, every mate sorts to his mate, every one brings another homeward of their way very friendly, and in their secret conclaves (covertly) they play the sodomites, or worse. And these be the fruits of plays and interludes, for the most part. (105)

If the play denaturalizes the relationship between signs and signifiers then how does it treat gender as opposed to sexuality? This question comes up again and again through the recurring motif of the doublet and hose (for men) and the petticoats (for women). In the passage below, Rosalind talks herself into gathering her strengths even though she is exhausted and hungry:

Rosalind. I could find in my heart to disgrace my man's apparel,

and to cry like a woman; but I must comfort the weaker vessel, as

doublet and hose ought to show itself courageous to petticoat;

therefore, courage, good Aliena.

Celia. I pray you bear with me; I cannot go no further.

- Explain Rosalind’s use of metonymy here. What are the gendered implications of her use of language?

- Is she like Orlando in some of the later scenes, wherein he comforts and provides for Adam?

- How “natural” is gender if part of being a good young man can be easily performed by putting on doublet and hose, and leaving off the petticoat?

- Is this what is troubling Stubbes when he says that “as [women] can wear apparel assigned only to man, I think they would as verily become men indeed”?

- How does the question about whether or not Rosalind wants to be the male object of Orlando's desire intersect with this discussion about how she can put on and take off her gender?

These are great questions for opening up the play to questions about gender, sexuality, clothing and theatrical history (especially in terms of religious dissent). Of course, these are very mature themes to be discussing in a high school English. I feel, however, that they are necessary topics to consider not only because advanced high school students and underclass undergraduates need to be challenged to think about the intersection of gender and sexuality but also because they really need to be challenged to think about how "natural" either gender or sexuality really is.

An untethered gayness... offers a way out of the emerging cul-de-sac of “born this way” political strategies, which limit us to a logic of bland, “don’t blame me” toleration rather than true pluralism.

--I Was Born Homosexual. I Chose to Be Gay. By J. Bryan Lowder

While I don't necessarily think that I would send my students to that link, I would try to get them to think about some of the core issues that the essay (and the term) raises: how radically free Rosalind is, and how her freedom is enticing to Orlando and helps to educate him so that he is ready to be in an actual partnership with her by the end of the play.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed