I like to pair Act 2 of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra with the "petticoat speech" that Queen Elizabeth gave after parliament tried to force her to marry and secure the succession of the monarchy. Here is the full citation if you are looking to find an authoritative source for the text, which is not a long text at all. Queen Elizabeth’s Speech to a Joint Delegation of Lords and Commons, November 5, 1566, Version 2 (aka “The Petticoat Speech”), anthologized in Elizabeth I: Collected Works, eds. Marcus, Mueller, and Rose (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), pp. 94-98.

The speech has several good points that are pertinent to a discussion of Shakespeare's play. The following excerpt is a useful starting point:

I did send them answer by my council, I would marry although of mine own disposition I was not inclined thereunto. But that was not accepted nor credited, although spoken by their Prince…I will never break the word of a prince spoken in a public place, for my honour's sake. And therefore I say again, I will marry as soon as I can conveniently, if God take not him away with whom I mind to marry, or myself, or else some other great let happen. I can say no more except the party were present. And I hope to have children, otherwise I would never marry. A strange order of petitioners that will make a request and cannot be otherwise assured but by the prince's word, and yet will not believe it when it is spoken…

The second point was for the limitation of the succession of the crown, wherein was nothing said for my safety, but only for themselves… I am sure there was not one of them that ever was a second person, as I have been and have tasted of the practices against my sister, who I would to God were alive again…There were occasions in me at that time, I stood in danger of my life, my sister was so incensed against me. I did differ from her in religion and I was sought for divers ways. And so shall never be my successor.

Then focus on this passage, for which the speech gets its nickname:

As for my own part I care not for death, for all men are mortal; and though I be a woman yet I have as good a courage answerable to my place as ever my father had. I am your anointed Queen. I will never be by violence constrained to do anything. I thank God I am indeed endowed with such qualities that if I were turned out of the realm in my petticoat I were able to live in any place in Christendom.

- Elizabeth calls herself both male ("Prince") and female (“though I be a woman”… your “anointed Queen”). What does she gain through each gendered position?

- How does Elizabeth use clothing here to construct her femininity and/or power? What is a petticoat? How would appearing in her petticoat confer power and/or powerlessness? How would appearing in her petticoat reveal or construct her femininity? Are power and femininity linked in this speech?

- Is her monarchical authority gender-neutral (“my honour”), male (“Prince”) or female (“petticoats”)? Is it English or is it trans-national?

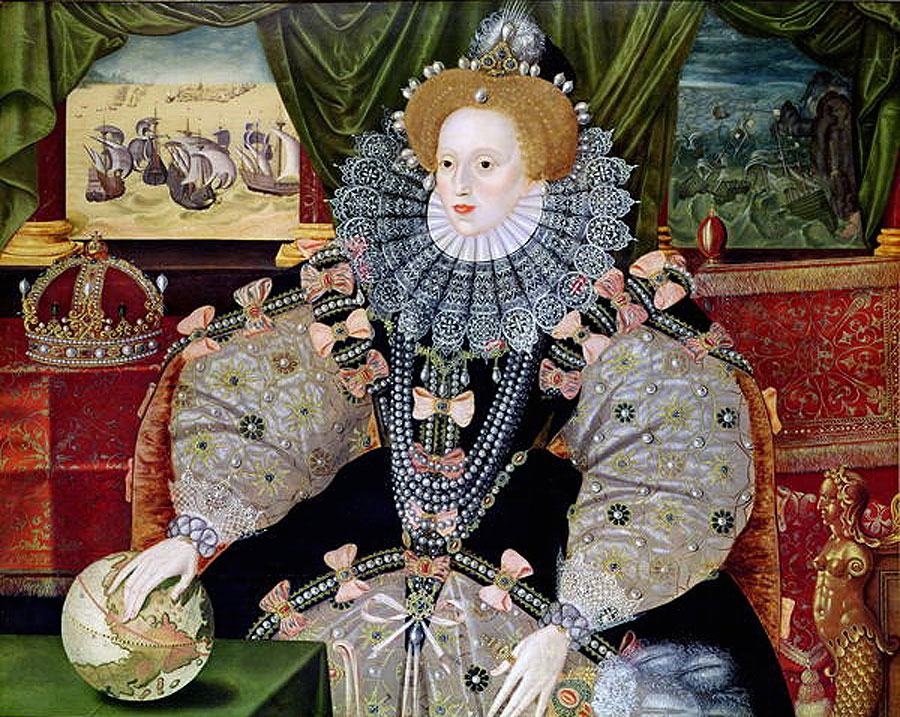

- Compare Elizabeth's use of clothing in this speech to the way that clothing works in the Armada portrait (in the lede image). How do her clothes in that portrait construct power?

- What does it suggest about Elizabeth that she is actually asking the House of Commons to picture her in her underwear—and that this is meant to cower them?

- Is Cleopatra like Elizabeth in any way? Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Does Shakespeare’s play seem to be anxious about female sovereignty?

One passage in Antony and Cleopatra that specifically mentions petticoats actually comes from Act 1, but it helps to highlight a lot of action in Act 2 as well. The following lines are spoken by Enobarbus after he and Antony learn of Fulvia's death:

Why, sir, give the gods a thankful sacrifice. When it pleaseth their deities to take the wife of a man from him, it shows to man the tailors of the earth; comforting therein, that when old robes are worn out, there are members to make new. If there were no more women but Fulvia, then had you indeed a cut, and the case to be lamented: this grief is crowned with consolation; your old smock brings forth a new petticoat: and indeed the tears live in an onion that should water this sorrow.

- Explain Enobarbus’ metaphor. How is a wife like a robe? How does she "[bring] forth a new petticoat"?

- Compare and contrast Fulvia and Cleopatra. Is either of them replaceable?

- Does Enobarbus like either Fulvia or Cleopatra? How do you know and why does it matter?

- How does this use of the petticoat metaphor compare to Elizabeth's use of it?

- Both Enobarbus and Elizabeth are using the petticoat imagery to discuss marriage, particularly a new marriage. What does marriage have to do with gender, power, and clothing?

This also leads to the very famous description that Enobarbus gives of the meeting of Antony and Cleopatra--like the Armada portrait above, this description presents female authority as a rich spectacle, a feast for the eyes.

The barge she sat in, like a burnish'd throne,

Burn'd on the water: the poop was beaten gold;

Purple the sails, and so perfumed that

The winds were love-sick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes. For her own person,

It beggar'd all description: she did lie

In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold of tissue--

O'er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature: on each side her

Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids,

With divers-colour'd fans, whose wind did seem

To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool,

And what they undid did.

- Enobarbus says that Cleopatra “beggar'd all description” but he talks a whole lot here. How do you reconcile those two claims? Is he talking about her or about the stuff around her?

- When we look at the Armada portrait, are we looking at Queen Elizabeth or are we looking at the stuff around her, particularly the clothes?

- How does the spectacle of female self-display relate to the repeated comparisons that are made between Cleopatra and food? Is she a feast for the palate as well as a feast for the eyes?

- There are many scenes in this play that are about other people’s thoughts about Antony and/or Cleopatra. We spend as much time hearing what people think about the two as we spend actually watching the eponymous characters. Why? Why are there so few soliloquies? How might that relate to clothing?

The description that Enobarbus gives also resonates with a scene late in Act 2, which once again ties Cleopatra to river imagery. Lounging around Alexandria while waiting for Antony, Cleopatra plays at fishing:

Give me mine angle; we'll to the river: there,

My music playing far off, I will betray

Tawny-finn'd fishes; my bended hook shall pierce

Their slimy jaws; and, as I draw them up,

I'll think them every one an Antony,

And say 'Ah, ha! you're caught.'

- Is she trying to “catch” Antony as in ensnare him with her charms (marry him)? Is her language more sinister? Is she like Salamacis who cries out “I’ve won!” when she sees Hermaphroditus dive into the water?

- Note that again she is associated with water imagery—elsewhere she is associated with the Nile (“Melt Egypt into Nile! and kindly creatures / Turn all to serpents!... So half my Egypt were submerged and made / A cistern for scaled snakes!”), and we already talked about her barge on the water when she first meets Antony. Why do you think she is associated with water? Compare and contrast that to the associations of her and food.

Thinking about Cleopatra in relationship to Queen Elizabeth is useful when we think about the ways that so many of the Romans cry out against her authority over Antony as an emasculating monstrosity. On the one hand she is threatening in the same way that John Knox found Mary Tudor to be threatening; however, there is something gorgeous, creative, and intoxicating about her self-conscious display of power. She is theatrical and seductive; she is a little bit like Queen Elizabeth, who had already died by the time that Shakespeare was writing this play. This strategy for presenting the play could give your students a way to conceptualize how Shakespeare may be nostalgically remembering Queen Elizabeth after her death.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed