I turned to my very smart friends on Facebook asking for advice, and here is what I got. (True story, the response I got to this post on Facebook was the inspiration for my blog. I first envisioned this blog as being called "My Smart Friends." So many people have commented to me that they love my pedagogy posts on Facebook because they draw ideas from so many smart teachers! I thought that it would be nice to have a more permanent place to keep these crowd-sourced ideas but I also wanted to contribute my own ideas as well because I love this gig, and I have perhaps too much to say about it).

The first set of advice comes from my lovely friend Gretchen Braun, who is an assistant professor at Furman University, a Victorianist, and a general bad ass with a totally sick muscle car.

Here is her advice:

I frame discussions of it around the impact of WWI and resistance to both Victorian culture and Victorian narrative conventions. My students have read Wuthering Heights first, so we get some mileage out of comparing Clarissa's choice between Richard and Peter to Cathy's choice between Edgar and Heathcliff (thinking about how this novel explodes the two-suitors marriage plot and figures it retrospectively). We also talk about Septimus in relation to changing paradigms of mental health and illness in the early twentieth century.

On Septimus and mental health

I talk about how nineteenth-century understandings of nervous disorders like neurasthenia (symptomology we would now associate with depression) totally failed in explaining and treating shell shock. Holmes and Bradshaw are following the "rest cure" approach to Septimus, and obviously, it's exactly what he does not need. See historian Janet Oppenheim's Shattered Nerves for information on nervous disorder/depression treatments in Victorian/Edwardian England. See also Cathy Caruth's theories of trauma and narration and talk about WWI as the beginning of modern trauma studies.

On the two-marriage plot:

Jean Kennard's Victims of Convention (there's an article and a book by that name) is an oldie but goodie. She outlines how the traditional female Bildungsroman requires a female protagonist to choose between two suitors who represent different cultural values. In choosing the "right" suitor she accepts his values, but loses her autonomy. Kennard talks about how this limits the kinds of female experiences the traditional novel can tell; obviously, it excludes maternity. Clarissa's story references the two suitors convention but insists that a woman remains fluid, interesting, and complicated after she has "chosen." And then of course there's all the interesting same-sex desire stuff in that book. Sharon Marcus's Between Women is an interesting lens for looking at Clarissa and Sally in their youth.

She would not say of any one in the world now that they were this or were that. She felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged. She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on. She had a perpetual sense, as she watched the taxi cabs, of being out, out, far out to sea and alone; she always had the feeling that it was very, very dangerous to live even one day. Not that she thought herself clever, or much out of the ordinary. How she had got through life on the few twigs of knowledge Fräulein Daniels gave them she could not think. She knew nothing; no language, no history; she scarcely read a book now, except memoirs in bed; and yet to her it was absolutely absorbing; all this; the cabs passing; and she would not say of Peter, she would not say of herself, I am this, I am that… Her only gift was knowing people almost by instinct, she thought, walking on. (200)

Here is her advice:

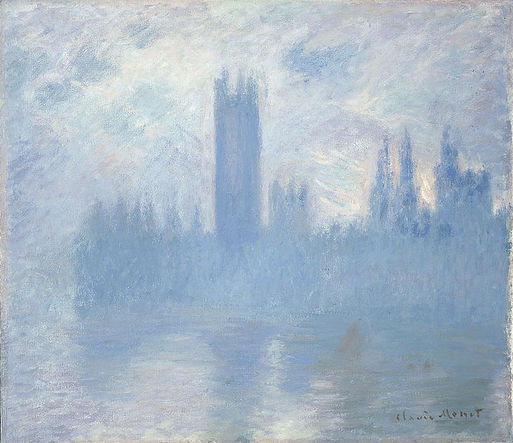

I'd second Gretchen's advice, but also point you in the direction of empire and imperialism. London itself is a character in the novel, and it's important to consider the urban space, and in particular the way that space is mostly limited to Westminster. It's the metropolitan center and focused even more on the state apparatus/government. Peter's recent return from India of course feeds right into this reading. Big Ben is the masculine time of governance and empire (and St. Margaret's, always two minutes behind is, at least in Peter's mind, feminine time).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed