I like to pair this act with the very brief passage that Bruce Smith excerpts from The Haven of Pleasure, Containing a Free Man's Felicity and a True Direction How to Live Well (1596) in his Texts and Contexts edition of Twelfth Night. Here are some of the pertinent passages:

But seeing that women desire to be decked and trimmed above all other creatures, who apparel themselves gorgeously to the end they may seem fair and beautiful to men, the apostle Peter warneth matrons that they bestow not too much cost on their world of furniture [clothing], not prostitute or set themselves to sale to such as may be them… but with modest attire, sober and not over-curious apparel, to please their husbands, by seeking to get their favors and good will.

But there are many in ours and our forefather’s time who appareling themselves with gorgeous apparel… have brought themselves to beggary and extreme poverty, who are then flouted of [insulted by those] such as helped them to spend their patrimonies, and of them also who by deceit, craft, cunning, and fraud have so scraped their wealth from them that they have not so much as a farthing to bestow on the relief of the poor that are brought to extreme penury and want.

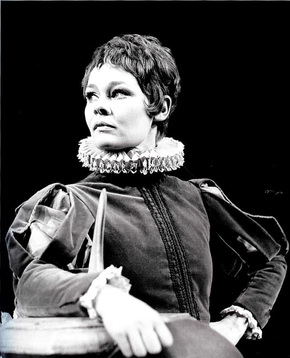

Fabian. O, peace! now he's deeply in: look how

imagination blows him.

Malvolio. Having been three months married to her, sitting in

my state,— Calling my officers about me, in my branched velvet

gown; having come from a day-bed, where I have left Olivia sleeping,— And then to have the humor of state; and after a demure travel of regard, telling them I know my place as I would they should do theirs, to for my kinsman Toby,— Seven of my people, with an obedient start, make out for him: I frown the while; and perchance wind up watch, or play with my—some rich jewel. Toby approaches; courtesies there to me, I extend my hand to him thus, quenching my familiar smile with an austere regard of control,—Saying, 'Cousin Toby, my fortunes having cast me on your niece give me this prerogative of speech,'— 'You must amend your drunkenness.’

How does Maria capitalize on her knowledge of Malvolio in the letter trick? Why does clothing play a part in her scheme? How is clothing a weapon?

It seems almost irresistible that the audience would be on the side of the conspirators against Malvolio. Does that lend weight to reading him as someone necessarily in opposition to the festive group (and maybe even playgoers)?

This discussion ties in with the scene between Olivia and Viola/Cesario that echoes both a passage from Exodus and a passage from another of Shakespeare's plays, Othello:

Moses said to God, “Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?”

God said to Moses, “I am who I am. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: ‘I am has sent me to you.’”

|

OLIVIA. Stay: I prithee, tell me what thou thinkest of me.

VIOLA. That you do think you are not what you are. OLIVIA. If I think so, I think the same of you. VIOLA Then think you right: I am not what I am. |

In following him, I follow but myself;

Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty, But seeming so, for my peculiar end: For when my outward action doth demonstrate The native act and figure of my heart In compliment extern, 'tis not long after But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve For daws to peck at: I am not what I am. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed