Before I dive into anything, I want to share a heart warming anecdote from my experience teaching this play. After the final exam, one of my male students hung back to talk to me as I was collecting the exams and saying goodbye. He had a story that he wanted to tell me that he had been too embarrassed to share up until that moment.

When he was studying for the exam, some friends of his drove to Davis from San Francisco to surprise him. He told them that he couldn't really hang out because he was studying for his English final, so they inquired about the material. When he told them that he was reviewing a play, they proposed that they act out the play together to help him study. So, they had a few beers together, and proceeded to stage an impromptu, private performance of Trifles.

If that wasn't adorably dorky enough--apparently, they got REALLY into it, and by the end of the play, all three boys were in tears thinking about poor Mrs. Wright and what she must have been going through to have gotten to the point where she snapped and killed her abusive husband. They were so worried about her and whether she would have to face consequences that her husband would never have had to face.

!!!!!

How amazing is it that three young men (hopefully all 21 by this time since they were probably also pretty drunk) spent their weekend together bonding over Trifles and thinking deeply about the ways that the justice system can be skewed toward the people who are already in power? God, being a teacher is the best job ever. That student, by the way, aced his final exam.

Onward to teaching strategies!

So this is another installment of "My Smart Friends," because I have lots of ideas to share with you that come from my friend Tiffany Gilmore, who is a general bad-ass. She is wicked-smart, hilarious, and generous; and she runs the full gamut between irreverently dirty-minded and pristinely proper--the type of lady who could make men blush at a hockey game and then turn around and whip up pistachio macarons that cause Martha Stewart to feel a deep sense of shame because she's been doing wrong all these years.

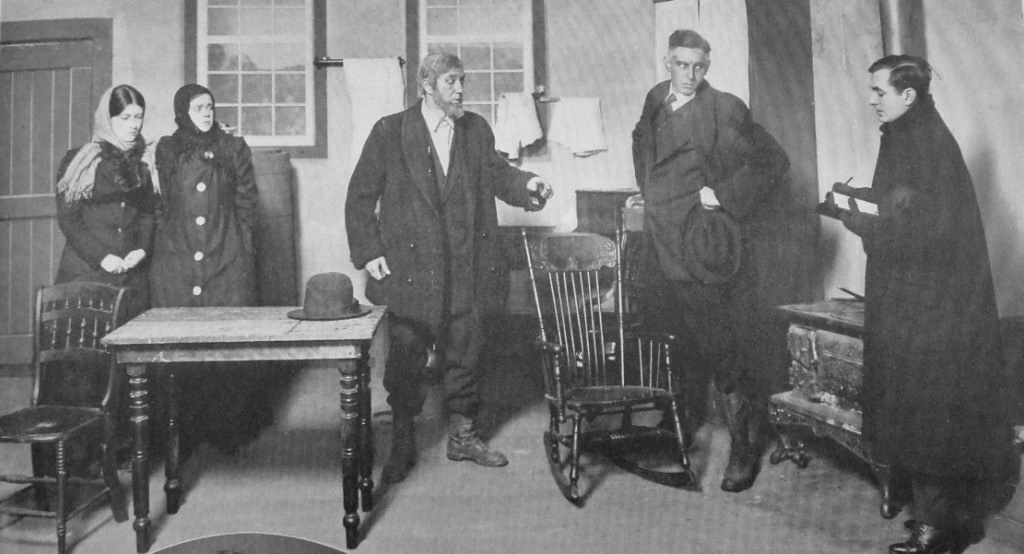

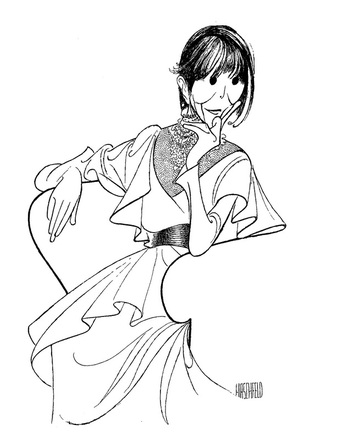

I have students read the image before we move into a discussion and I'm always surprised how well that activity goes; someone always gets reading the body language of men taking up space and being important and the women looking down, folded in on themselves in the background as well as the starkness and cold of the setting.

Tiffany recommends also starting with an in-class writing prompt for the first 10 minutes of class: are the women justified in hiding their findings from the men, why or why not? This generates a really good discussion on justice, versus morality etc.

Both Tiffany and I have had the experience that each term some students are adamant that withholding information is absolutely illegal because someone was murdered and some think that--while not exactly legal-- it is at least understandable because Mrs. Wright was at the very least emotionally abused, and her alibi is so weak, that she will probably be found guilty anyway.

I like to hold a mock trial for Mrs. Wright, using as "evidence" passages from the play itself--this is good for their papers because students start gathering textual evidence immediately. I divide the classroom into two: a prosecution side that argues for the charge of first degree murder with a death penalty sentence and a defense side that can either argue for innocence ("not guilty by reason of insanity") or for a lesser crime like manslaughter. I usually act as judge, but it could be cool to assign an actual jury in the classroom along with a student judge.

My activity differs from Tiffany's because she's asking students to judge Mrs. Peters and Mrs. Hale whereas I am asking students to judge Mrs. Wright. We might then go to the next logical step and ask students to consider if there is anyone or anything else that we could or perhaps should be judging. Who or what is really on trial in this play?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed