Here are some of the passages that resonate with Columbus' Letter to Luis de Santangel regarding the First Voyage and his letter to Ferdinand and Isabella regarding the Fourth Voyage.

Horace begins his poem with a lamentation about the destruction that the Romans have done in their Civil War:

What the neighbouring Marsians could not destroy,

Nor the threat of Porsena’s Etruscan armies,

Nor Capua’s rival strength, nor the fierceness of Spartacus,

Nor the Gauls, who proved disloyal in changing times,

Nor that savage Germany he conquered, with its blue-eyed youth,

Nor Hannibal detested by our ancestors:

Our impious generation, of cursed blood, will destroy,

And the land will belong again to beasts of prey.

One way to paraphrase this section is to say neither this guy, nor that guy, nor this enemy, nor that enemy, none of them has been able to destroy us; through out wickedness, we ourselves have destroyed what our enemies could not.

This paraphrase helps to develop the general statement about emphasis and it also points the students towards thinking about this poem as employing a combination of patriotism (no one defeated us) and shame (we are an impious generation). Here the students can see that the poem is still a propagandistic poem that ultimately praises Rome for its past glory even as it bemoans the present political upheaval. It sets up a lovely point of contrast with the end of the poem, where Horace describes the isles of the blest.

The total devastation of Rome through civil war creates a desolation that pushes the virile out of their former city. Quite simply, it is impossible to stay and it is impossible to return. Instead, Horace (either rhapsodically or ironically) prophecies that they will head out for these mythical islands:

You who have courage, away now with womanish weeping,

Sail on swiftly beyond the Etruscan shores.

The encircling Ocean is awaiting us: let us seek out

The fields, the golden fields, the islands of the blest,

Where the land, though still untilled, yields a harvest every year…

Jupiter set aside these shores for a virtuous people,

When once he had dimmed the age of gold with bronze:

With bronze, with iron, he made the centuries harder, from which

My prophecy grants the virtuous sweet escape.

I thought it was worth it to ask my students to talk about the idea that the land, though untilled, would still yield harvest. Intriguingly, some of my students suggested that this was a sign of "laziness" on the part of the Romans; that they wanted to reap the harvest without doing the hard work of farming. This lead to an interesting debate wherein some students maintained this idea whereas other suggested that, in Horace's poem, the land seemingly offers itself to them as a reward for their virtue. They have suffered, but now they won't any more. They see themselves as entitled to this land, which is part religious paradise and part fantasy. Horace's description is not a sign of laziness but a sign of hope.

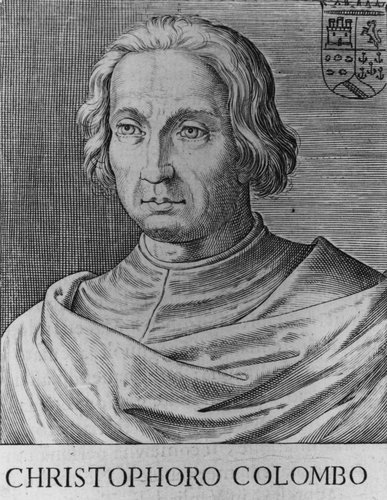

The imagery and the themes of this poem dovetail beautifully with Columbus' letters. These are both excerpted in the Norton Anthology of American Literature. The first letter really captures the themes of both wonder and entitlement. In the second letter, Columbus' attempts to self-fashion as a hero even as his legacy is being tarnished and his honors are stripped away.

Here is a snippet from the first letter:

This island [Hispaniola] and all the others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so. In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison with others which I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which is marvelous… All are most beautiful, of a thousand shapes, and all are accessible and filled with trees of a thousand kinds and tall, and they seem to touch the sky. And I am told that they never lose their foliage, as I can understand, for I saw them as green and as lovely as they are in Spain in May, and some of them were flowering, some bearing fruit, and some in another stage, according to their nature. And the nightingale was singing and other birds of a thousand kinds in the month of November there where I went…

- As your footnote mentions, the nightingale and the honeybee (which Columbus refers to obliquely later in the letter) are not native to the Western Hemisphere. Why does he mention them (even indirectly)?

- Compare and contrast this description of what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic to the fictional Isles of the Blest that we read in Horace.

This lead to a great discussion about whether or not Columbus seems to think that the Indies are some sort of reward to which he is entitled because of his virtue, past toil, and the glory of the empire for which he is writing. I direct students to the following passage to develop this discussion:

I passed from the Canary Islands to the Indies with the fleet which the most illustrious king [...] our sovereigns gave to me. And there I found very many islands filled with people innumerable, and of them all I have taken possession for their highnesses, by proclamation made and with the royal standard unfurled, and no opposition was offered to me. To the first island which I found I gave the name San Salvador, in remembrance of the Divine Majesty, Who has marvelously bestowed all this; the Indians call it "Guanahani." To the second I gave the name Isla de Santa Maria de Concepción; to the third, Fernandina; to the fourth, Isabella; to the fifth, Isla Juana and so to each one I gave a new name.

The topic of how Columbus develops a persona for himself is a useful transition to the second letter:

The fear of this, with other sufficient reasons, which I saw clearly, led me to pray your highnesses before I went to discover these islands and Terra Firma, that you would leave them to me to govern in your royal name. It pleased you; it was a privilege and agreement, and under seal and oath, and you granted me the title of viceroy and admiral and governor general of all...

The other most important matter, which calls aloud for redress remains inexplicable to this moment. Seven years I was at your royal court, where all to whom this undertaking was mentioned, unanimously declared it to be a delusion. Now all, down to the very tailors, seek permission to make discoveries...

Who will believe that a poor foreigner could in such a place rise against Your Highnesses, without cause, and without the support of some other prince, and being alone among your vassals and natural subjects, and having all my children at your royal court? … It must be believed that this was not done by your royal command. The restitution of my honor, the reparation of my losses, and the punishment of him who did this, will spread abroad the fame of your royal nobility.

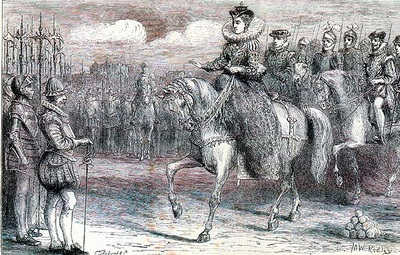

Here a comparison with Horace is helpful. Although Horace mentions the "impious generation" (a note of shame) he does so in a way that emphasizes the past glory of Rome (a note of pride). While Columbus does discuss his relative lowliness and disgrace ("poor foreigner," "vassal"), he does so in a way that emphasizes his past heroic deeds. The idea of Columbus as a hero is one that gets picked up in later history as well. For this reason, I like to bring in 19th century paintings of Columbus.

I like to ask my students to study the three paintings and look for recurring motifs. Then I ask them to consider if they are propagating a myth of Columbus that he has set in motion in his own letters. I ask them to point to the particular passages in the letter that a painter might conceivably be thinking about.

Although Columbus might not have read Horace directly and the painters might not have read Columbus' letters, neither Columbus nor the nineteenth-century painters were working in a vacuum. Myths of heroism tend to accumulate over time. They become archetypal, drawing from recurring patterns in our culture and affecting the way we see the world around us and our place in it. This unit is just as much about myth-building as it is about close-reading.

With that in mind, I think that it is absolutely necessary to consider counter-narratives about Columbus that are much more critical of his actions. To this end, I ask student to read critiques of Columbus, both ones that were contemporary to him and ones that are contemporary to us, as I have written about before. I think that it's important to consider writers like Bartolmé de las Casas because he offers us proof that people in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries were fully capable of seeing the humanity in the Native Americans and that the encomienda system that Columbus helped to establish was not an inevitable consequence of the Europeans' discovery of the Americas.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed