Katie's background is in Classics and mine is in Early Modern English literature, so we divided our class time between Sophocles' Antigone and Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice. The pairing of these two plays was really useful and productive--and I will be forever wanting to pair the two again after this fruitful summer class!

Day 1: Antigone

- Creon and the Watchman, (ll. 233-330)

- Creon and Antigone, (ll. 450-580)

- Haemon and Creon, (ll. 631-780)

- Creon and Chorus, (ll. 1261-1353)

These close-reading question lead to a larger group discussion about human and divine law. The capstone discussion was centered on teasing out what "human" and "divine" law might mean. What are the traits of a good judge? Does Creon qualify as a good king or a good judge? Are these roles mutually exclusive? Which is more fair, divine justice or human justice? What is the different between justice and revenge? Who has greater authority behind their claims: Creon or Antigone? The play is called Antigone. Why not Creon?

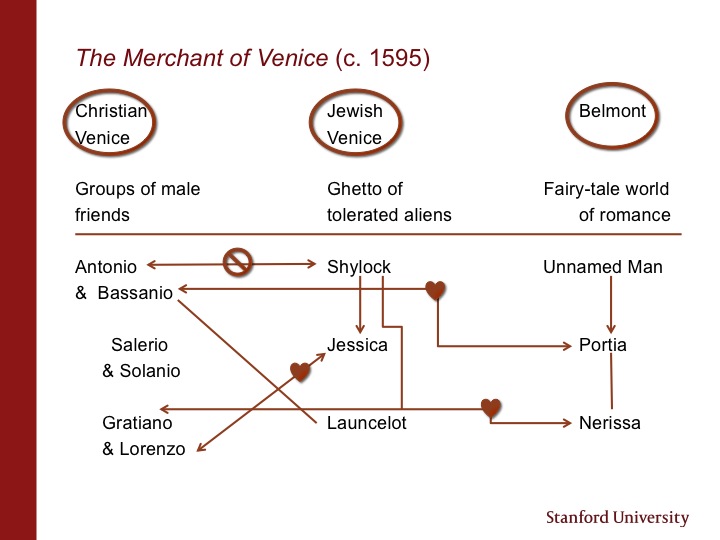

Day 2: Merchant of Venice

- 3.1: “Hath not a Jew eyes?” (whole scene)

- 4.1.145-415: the trial scene (from the reading of Bellario’s letter to Shylock’s exit)

| In preparation for our discussion of 4.1, I asked my student to consider this Early Modern emblem of mercy: “Mercy Overcoming Revenge,” from Richard Day’s A Book of Christian Prayers (London: Printed by Iohn Daye, dwellyng ouer Aldersgate, 1581). The text accompanying the image reads, “Mercy beareth with infirmities. Cruelty seeketh revenge.” Compare this image to Portia’s speech at 4.1.179: “The quality of mercy is not strained.” What is Portia saying in her monologue? In what way is Portia associated with mercy? Does Portia “bear with infirmity,” as the image suggests is necessary? How does Portia win the trial? In what way could Portia be associated with revenge? Although Shylock does “bear with infirmity,” can he be at all associated with mercy? Why or why not? When Shylock says that he “crave[s] the law,” does that mean that he represents justice? |

Day 3: Synthesis and Screenwriting

In 1360–1, English Justices of the Peace were given power by statute to ‘arrest all they may find by indictment or suspicion’. Statutes passed in 1554 and 1555 forced a transformative refinement in the older legal concept by requiring Justices to take written examinations of those arrested to record the grounds on which they decided to detain a suspect in prison or, alternatively, to grant bail. In order to comply with these statutes, Justices of the Peace had to find ways of weighing likelihoods applicable to all kinds of cases. They had, effectively, to become experts in the ‘invention’, or finding, of arguments of suspicion: to do so, they turned, just as poets, dramatists, and other writers were doing, to Latin treatises in rhetoric, especially Cicero...

[The] sixteenth‐century English [system] of judgment could… be said to be based on the participation of lay persons (justices, victims, neighbours, jurors) in deciding what was to count as knowledge. The English criminal justice system, as Barbara Shapiro writes, put ‘great faith both in witness observers and in jurors as “judges of fact” ’, that is, as evaluators of contradictory witness testimony. Sixteenth‐century developments in the participatory justice system involving the taking of written examinations by Justices, and the need for jurors to evaluate evidence at the bar, were directly engaging the very same questions of probability and likelihood with which dramatists were beginning to be concerned.

One outcome of this discussion helps to link Antigone and Merchant of Venice together. Hutson is basically arguing that changes in the legal culture in England contributed to a flourishing of drama during early modern period. That is, because suspicion was "socially pervasive" in legal culture, dramatists re-conceptualized the way they wrote characters. This was necessary in part because they had new ways to talk about character and in part because they had to meet the demand for new tastes in their audiences/juries. We can now imagine that characters can lie, either to other characters or to themselves; part of the thrill of being an audience member, or indeed a jury member, is trying to find out the hidden, secret truth behind the words and actions of a character or suspect. This is in distinction from Ancient Greek tragedy, where we see two philosophies brought into conflict with each other. Whereas Shylock might be lying to Antonio when he offers the bond as a sign of "kindness," Creon is never lying to Antigone when he explains his conception of justice to her. He is a complicated character and represent a complex philosophy, but with Creon (as with all characters in Ancient Greek tragedy) there is no secret agenda.

We then go back in time for a bit to consider the implications of Hutson's claim for Greek drama and modern pop culture in America:

- How might democracy have trained people to be enthusiastic consumers of drama?

- Might drama have trained people to be more active participants in a democracy? How so?

- In your opinion, does our modern legal system in America train us to be critical consumers of culture?

- Conversely, does our culture train us to be active participants in the legal system?

- Are those ideas totally separate?

From here, Katie and I gave our students the task of adapting the two plays into their own language, using their own scenarios. The screenings of the two films were really valuable contributions to this discussion. Antigone was particularly useful because the movie had been filtered first through Jean Anouilh and then again through PBS. We had four total performances this year: two of Antigone and two of Merchant of Venice. Students wrote their adaptations collaboratively in small groups outside of class time--alas, it was impossible for us to avoid homework all together.

Day 4: Inside the Actor's Studio and Performance

- Why did you choose to adapt your play in this way? If you make allusions to a particular moment in history or pop-culture phenomena, explain what it is about this particular reference that seems enlightening to you.

- What was difficult to adapt in your original play? What was easy to adapt? Why do you think that somethings were easy to adapt and some things were hard?

- What did you learn about the original play through the process of adapting it?

- What did you learn about OUR culture through the process of modernizing the play?

- How have you performed justice? How is it different from revenge?

These questions were essential for raising the bar for students. In each class, there was one group that paid closer attention to the language of the original play. One Merchant group changed the Jewish Shylock into a rich Muslim named Amir and set the play in post-9/11 New York City. They wanted to highlight how racial stereotyping would bring out the worst in any group. One Antigone group set the play in a gang-infested urban center; Creon has risen to power after the gang divided against itself. This group highlighted the misogyny in Sophicles' play by focusing on the violence that Creon threatens upon Antigone for calling his authority into question. Both of these groups closely followed key scenes in the play such as the "hath not a Jew eyes?" scene and the agon between Creon and Antigone.

We wrapped up our course with a performance for all of the Summer Program. Because the movie screenings had drawn a number of students, people were interested to see how their classmates would adapt the plays. It was a really, really great way to end the course. The audience was engaged and lively. They audibly gasped at times--particularly during moments of racism or misogyny as depicted by the post-9/11 group and the gang group, respectively. They cheered when Amir (the revised version of Shylock) gave his defiant speech "don't Muslims have eyes too?" or when Antigone didn't flinch at all, even after Creon turned a knife on her. And they laughed along with the dark comedy of the adaptations--the ridiculous idea that a teenage "mean girl" could somehow cow her friends and family into covering up a murder and a festering body.

I would highly recommend this course--or an adaptation of it--to teachers working on a unit about law and literature. We crammed more into four days than most teachers could probably do (especially by holding screenings after "school" was out for the day), but the course could be expanded to allow for classes to read the full texts and screen the film in class. Katie and I had so much fun that we're already planning on what we'll do next summer!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed