In the past five posts, I have outlined an archive of images and demonstrated how visual analysis of images such as these can foster strong close-reading practices among undergraduate and advanced high-school students. Now I would like to turn my attention to the import of the digital medium in which my students are consuming the images.

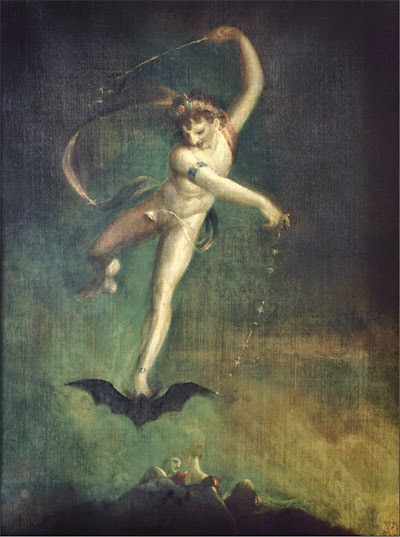

What is different about viewing these images online instead of on a projector in a classroom, in a museum, or in a rare-book room where one might find an older edition of Shakespeare containing, for example, engraved illustrations?

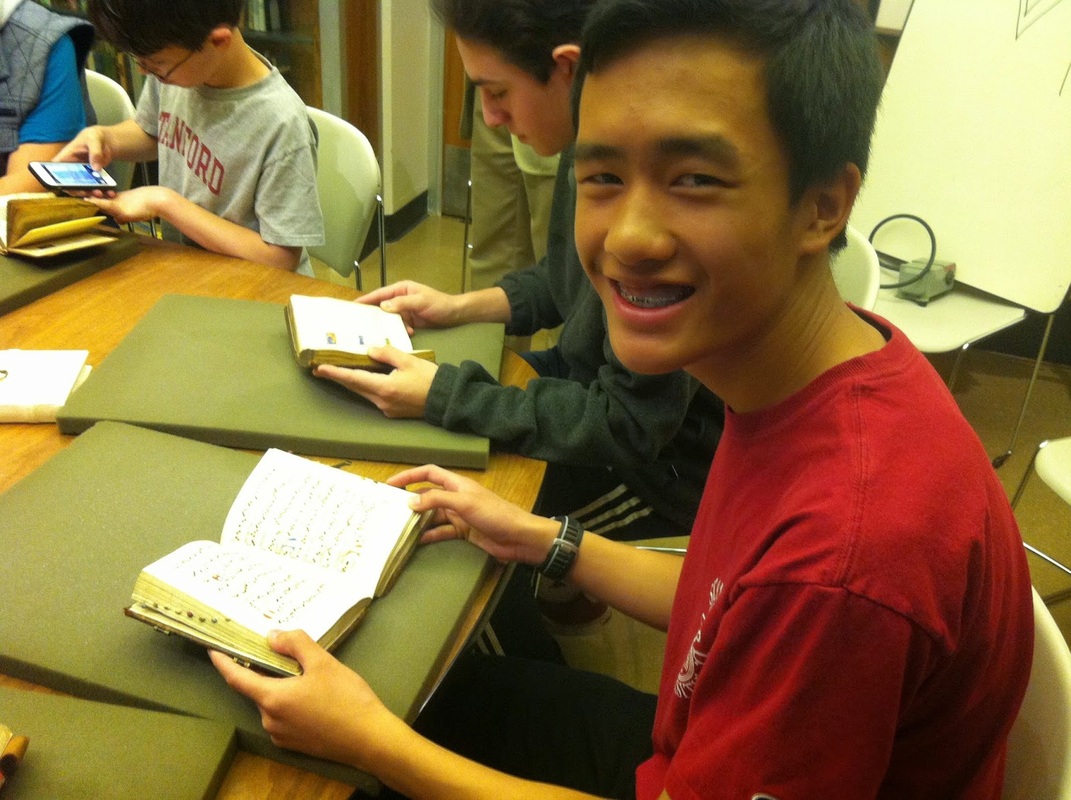

This brings me to a second effect of the democratization of images: whereas a painting or an illustration in a rare book can be fetishized to a certain extent, the proliferation of images through digital media makes an image more intellectually accessible for younger students. Anxiety about speaking about an image just isn’t as great when we diminish the magical qualities frequently associated with curated and archived objects and images. Rather than looking at an image in a museum or a library, students are consuming the image in their own spaces.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed